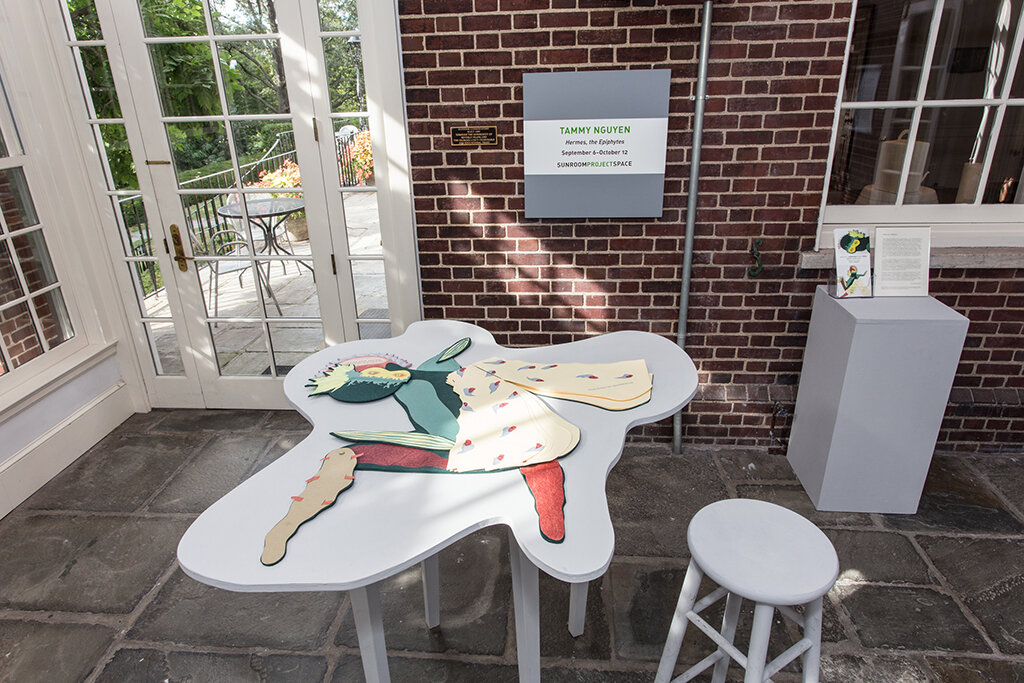

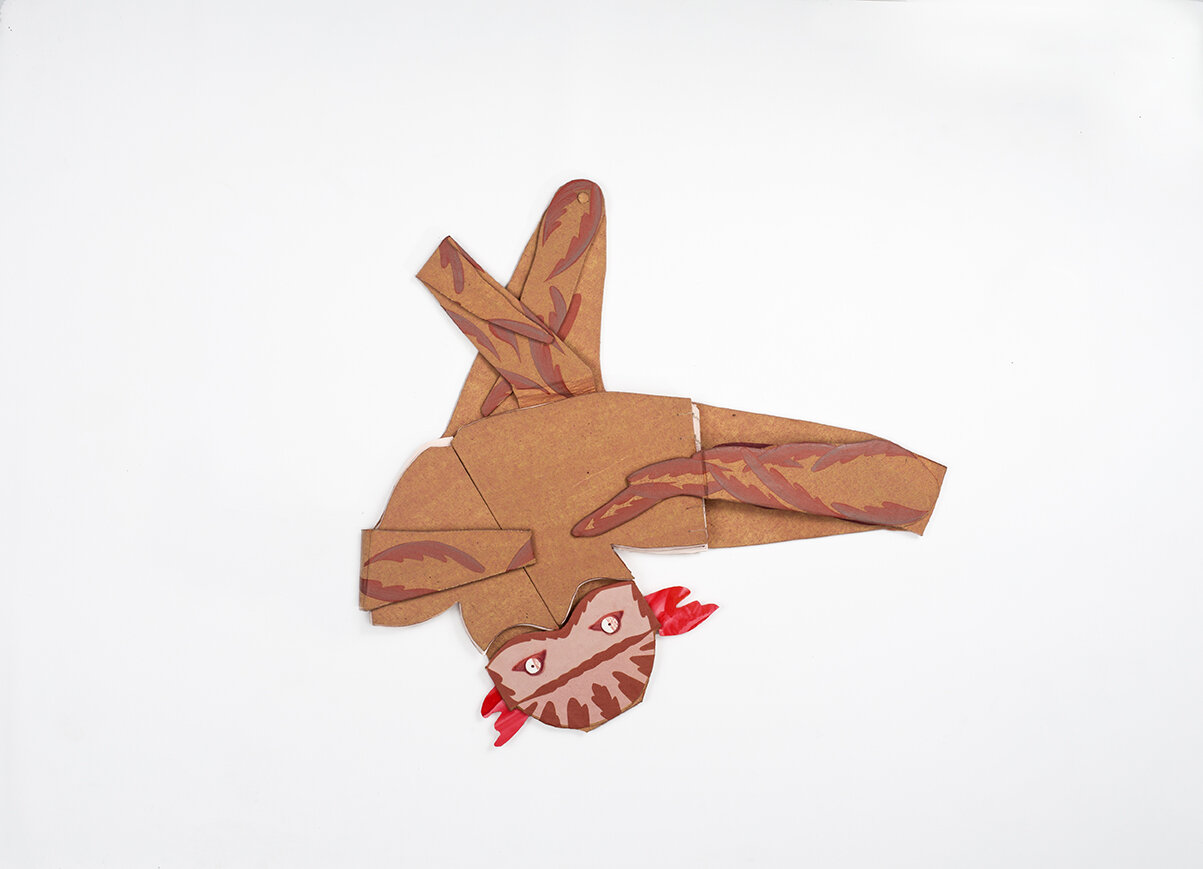

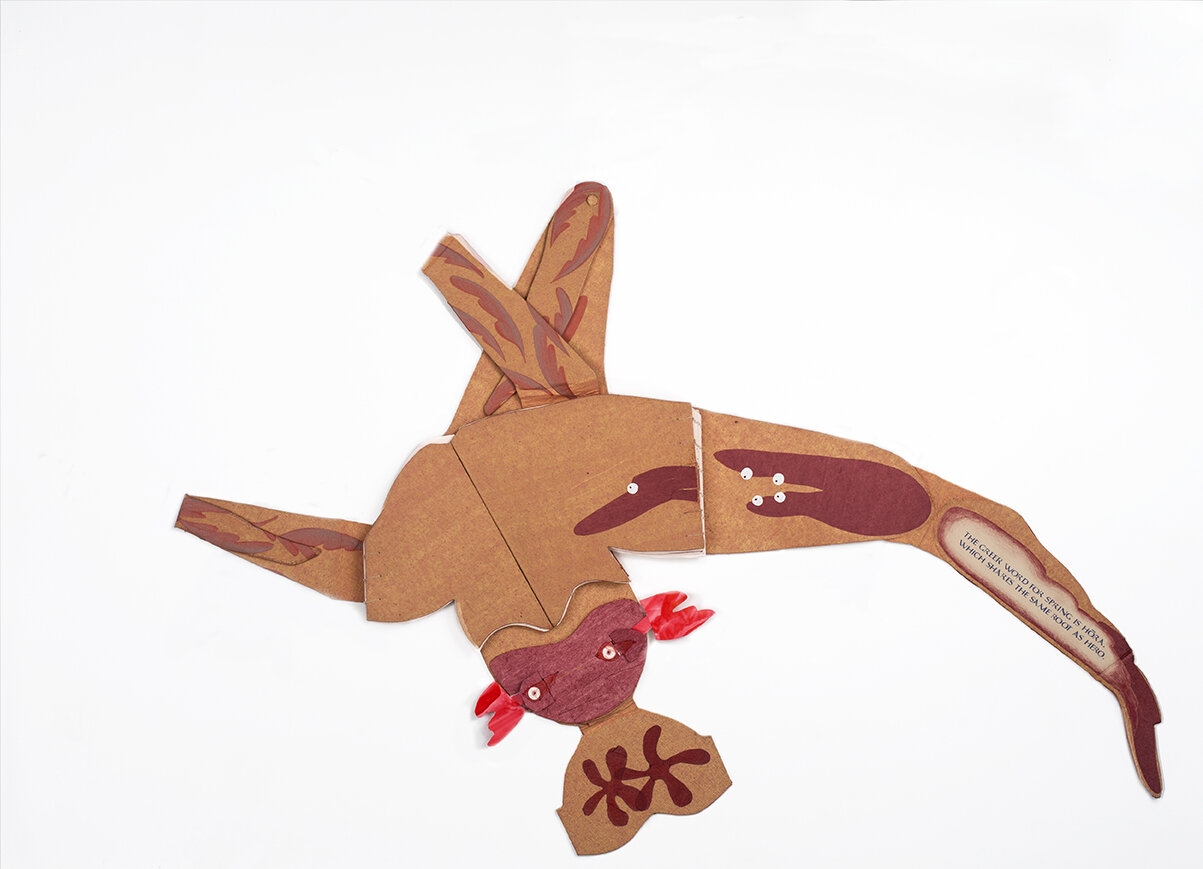

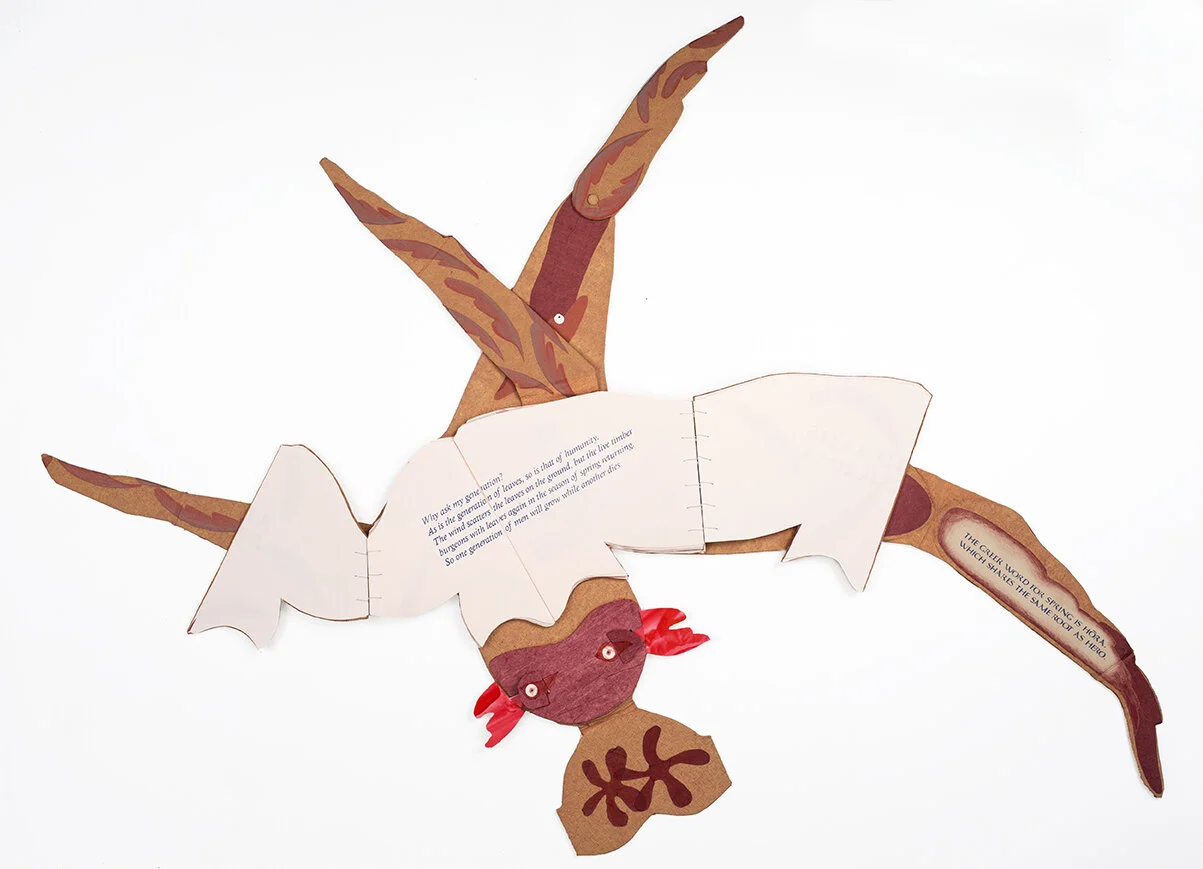

Hermes, the Epiphytes

“Hermes, the Epiphytes” was a solo exhibition in the Sunroom Porch of Wave Hill in the Bronx NY in 2014. It was an exhibition of three artist books.

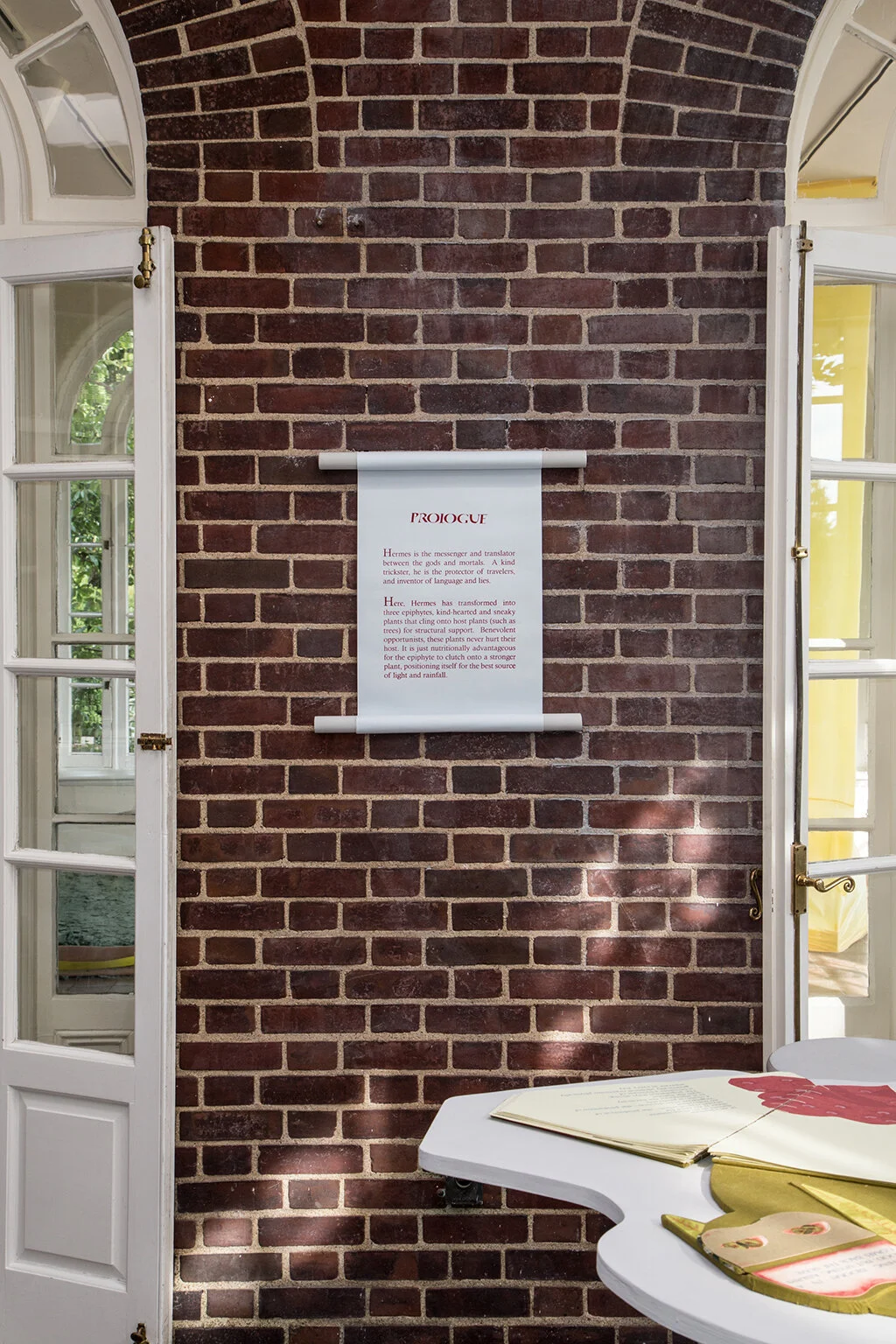

Prologue

Hermes is the messenger and translator between the gods and mortals. A kind trickster, he is the protector of travelers, and inventor of language and lies.

Here, Hermes has transformed into three epiphytes, kind-hearted and sneaky plants that cling onto host plants (such as trees) for structural support. Benevolent opportunists, these plants never hurt their host. It is just nutritionally advantageous for the epiphyte to clutch onto a stronger plant, positioning itself for the best source of light and rainfall.

Bromelia Neoregelia

The Greek word for spring is hora, which shares the same root as hero.

Why ask my generation?

As is the generation of leaves, so is that of humanity.

The wind scatters the leaves on the ground, but the live timber

burgeons with leaves again in the season of spring returning.

So one generation of men will grow while another

dies.

There is an ecosystem

inside of the bromelia neoregelia,

the epiphyte that clings onto

the large trunks of trees by its roots.

The center of the plant is a cup

that holds rainfall. It is a pond where

all of the flowers grow.

Many emerald green buds stick

their tops through the surface of the water.

The buds are wet and glimmering; seductive

as you try to glimpse at your reflection.

The green and yellow leaves

of the bromelia neoregelia

wrap around the center cup.

They are secured to

the root of the plant,

dig into the base, and

extend outward towards

the air.

You always know when

the flowers are coming

because the leaves of

the bromelia neoregelia bleed

a pomegranate color. The red floods

the green and yellow stripes,

making the leaves monochromatic.

You always know when

the heroes are coming

because the leaves of

the bromelia neoregelia bleed

a pomegranate color. The red floods

the green and yellow stripes,

making the leaves monochromatic.

It is Achilles who is bleeding, and his

mother is wailing.

She gave birth to the perfect son,

half god, half mortal.

He was without fault and powerful,

conspicuous among heroes as he

shot up like a young tree.

She nurtured him like a young tree

grown in the pride of the orchard.

Achilles should die,

because when you see him live,

and he looks on the sunlight,

he has sorrow,

and you can do

nothing to help him.

He has sorrow that you

can do nothing about

because he does not believe

that he will be immortalized by

the new generations of

men in poetry.

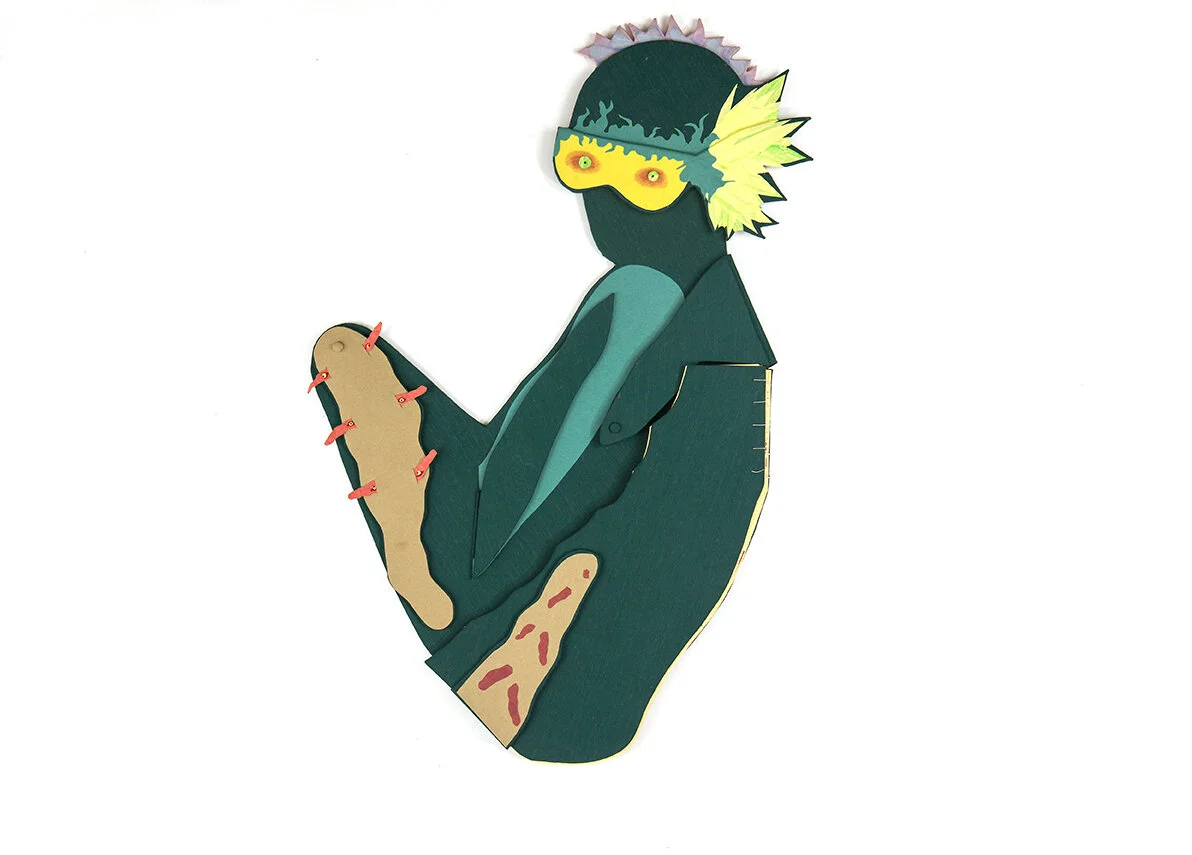

detail

He has sorrow

that you can do

nothing about because

he does not believe

that he will be immortalized by

the new generations

of leaves that the wind

scatters on the ground.

The flowers of

the bromelia neoregelia

shoot up like young trees.

They appear in a startling

blue color,

the kind of blue you see on Pluto.

The petals look

like tissue paper

sticking out of a box.

But like tissue paper,

their time is short,

and they wrinkle up

and fall away.

These flowers die upon full bloom.

Achilles dies upon full bloom.

But soon, the roots sprout

a genetically identical

bromelia neoregelia and

the life cycle of the epiphyte continues,

still clinging

onto the large trunks of trees

by its roots.

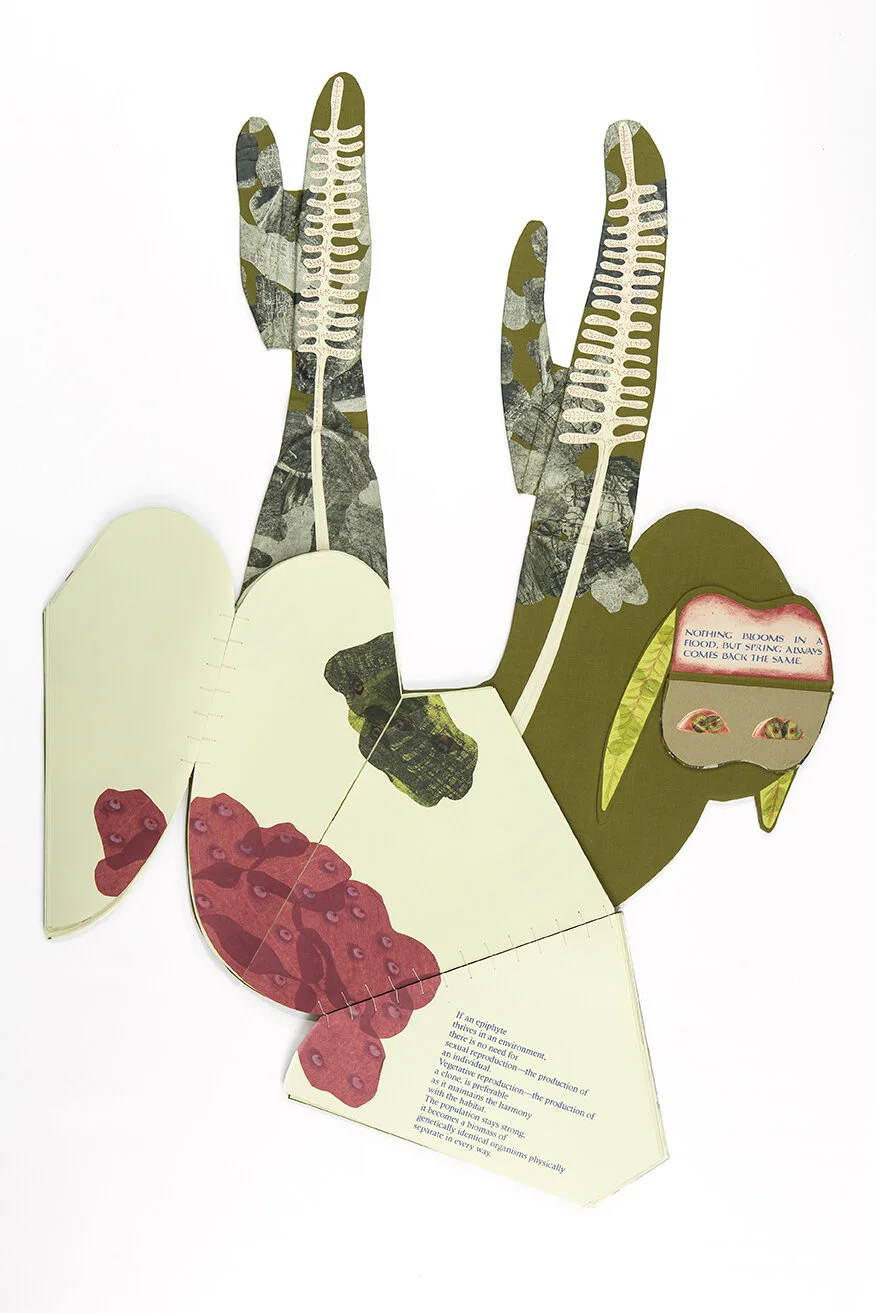

If an epiphyte

thrives in an environment,

there is no need for

sexual reproduction—the production of

an individual.

Vegetative reproduction—the production of

a clone, is preferable

as it maintains the harmony

with the habitat.

The population stays strong;

it becomes a biomass of

genetically identical organisms physically

separate in every way.

The epiphytes always come back the same,

and the bromelia neoregelia always dies

in full bloom.

The heroes always come back in the spring,

and Achilles always dies

in full bloom.

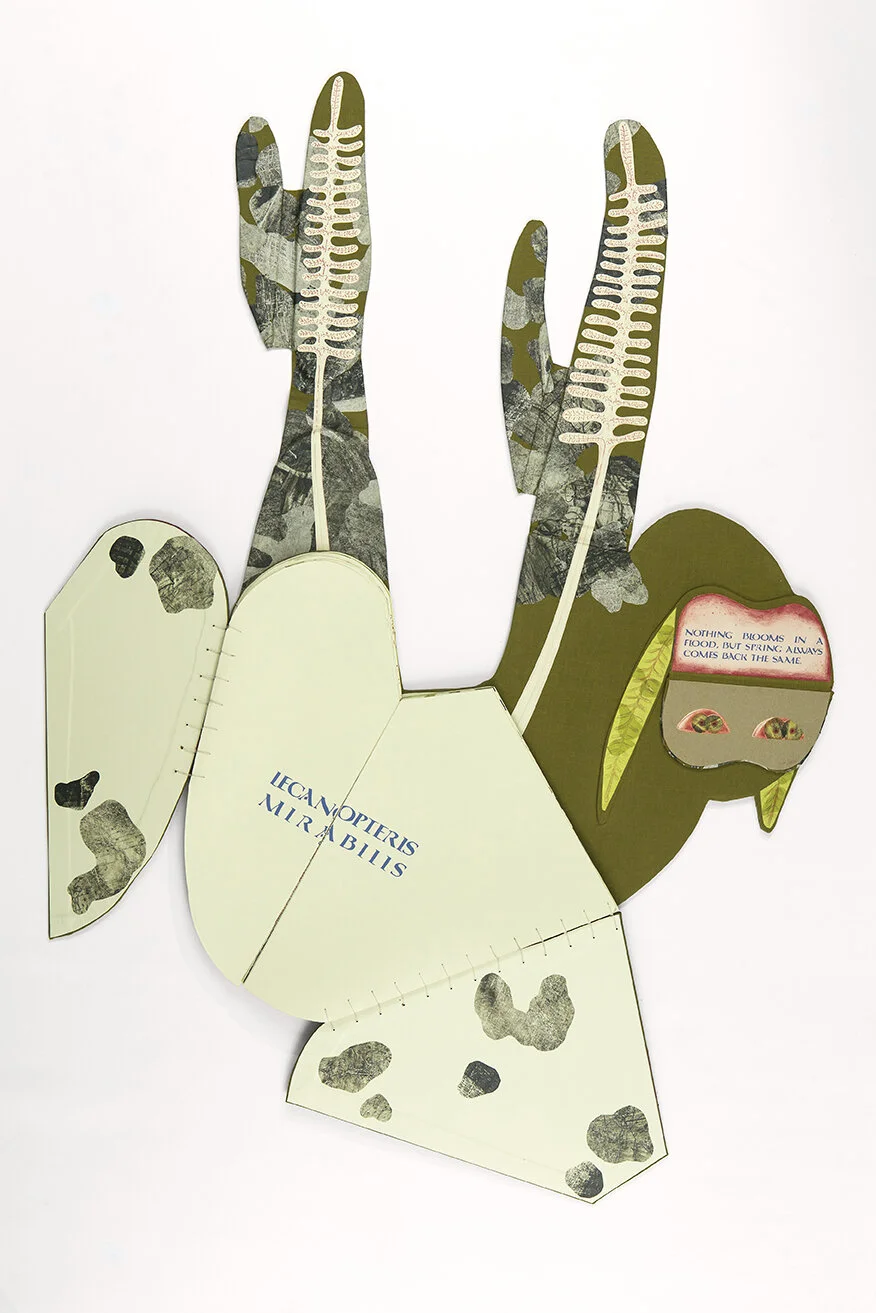

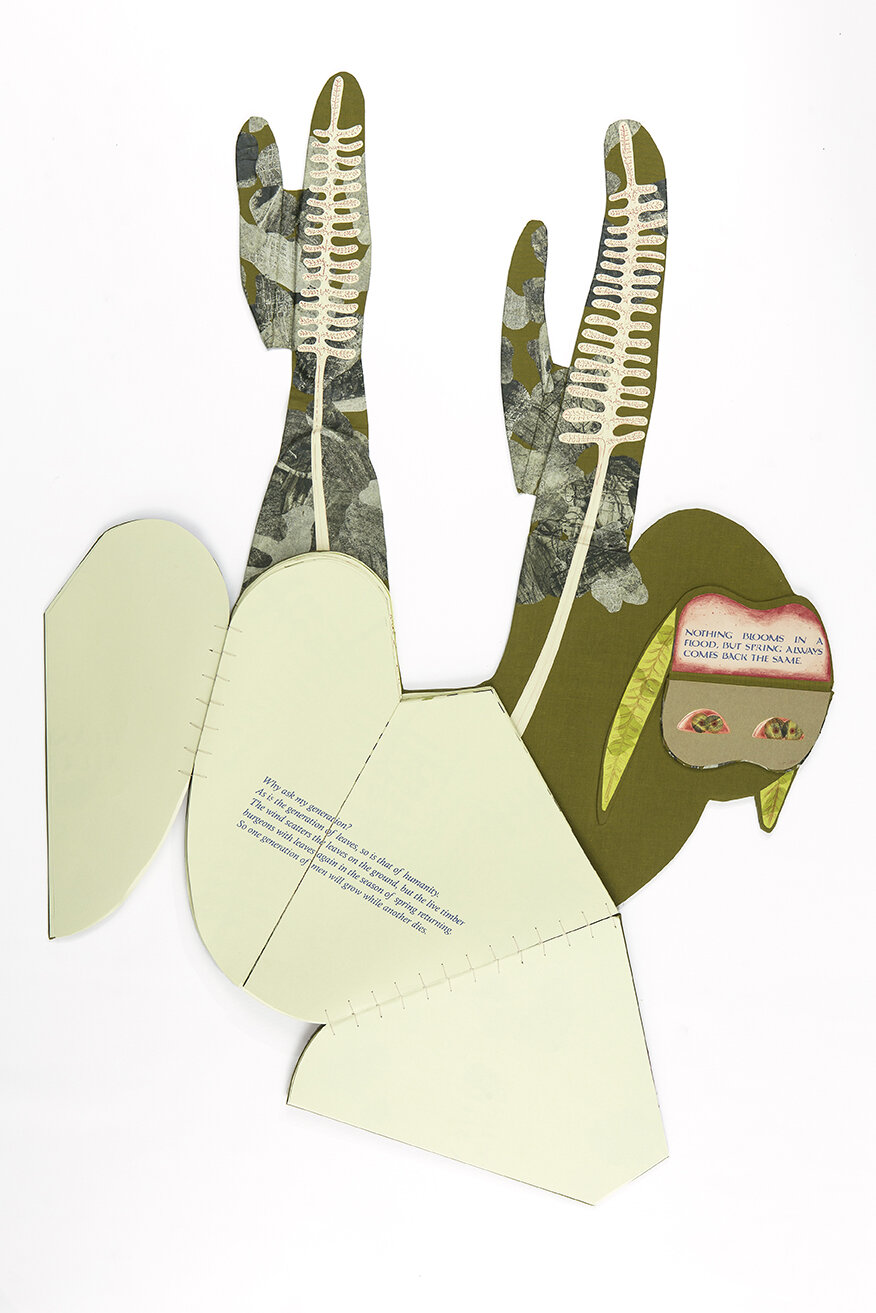

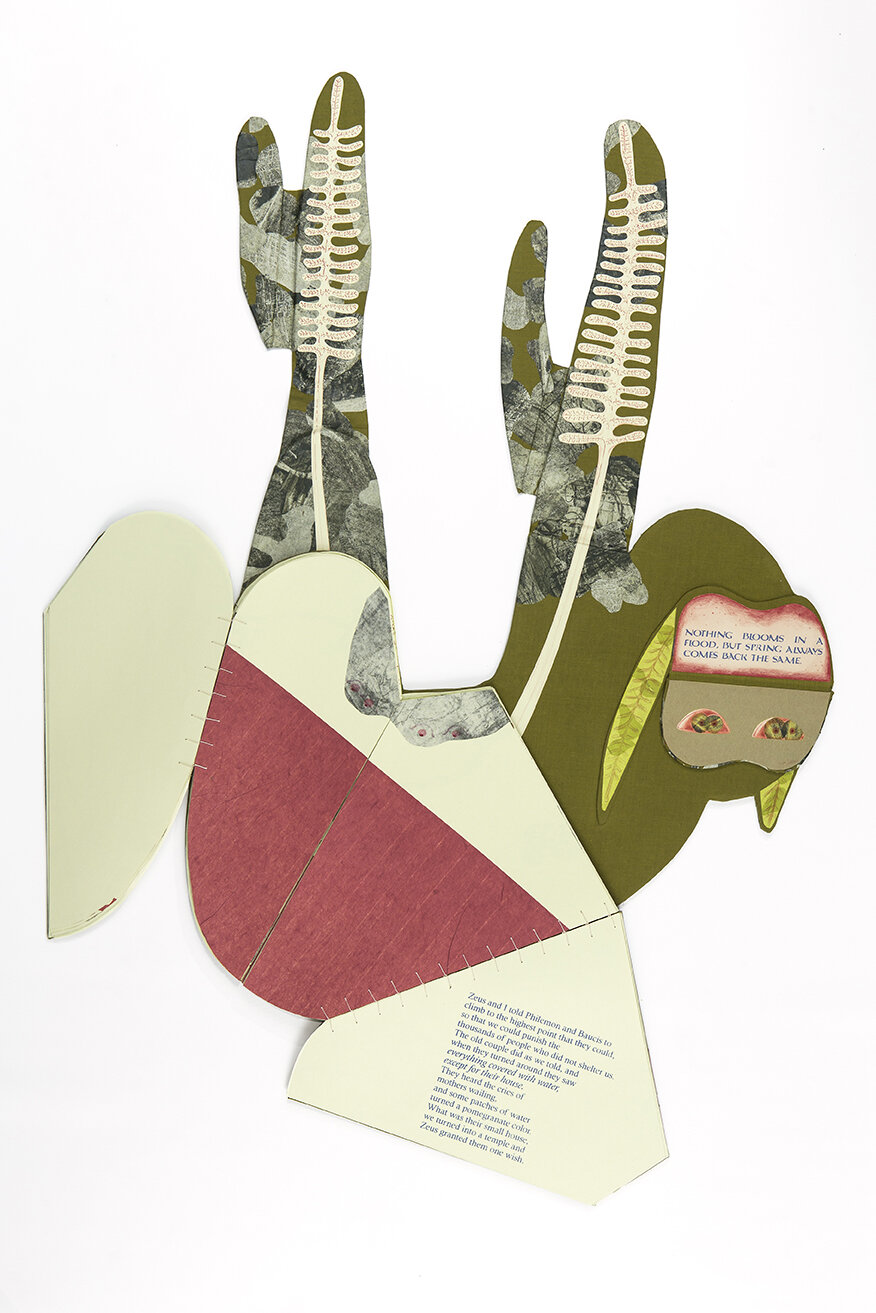

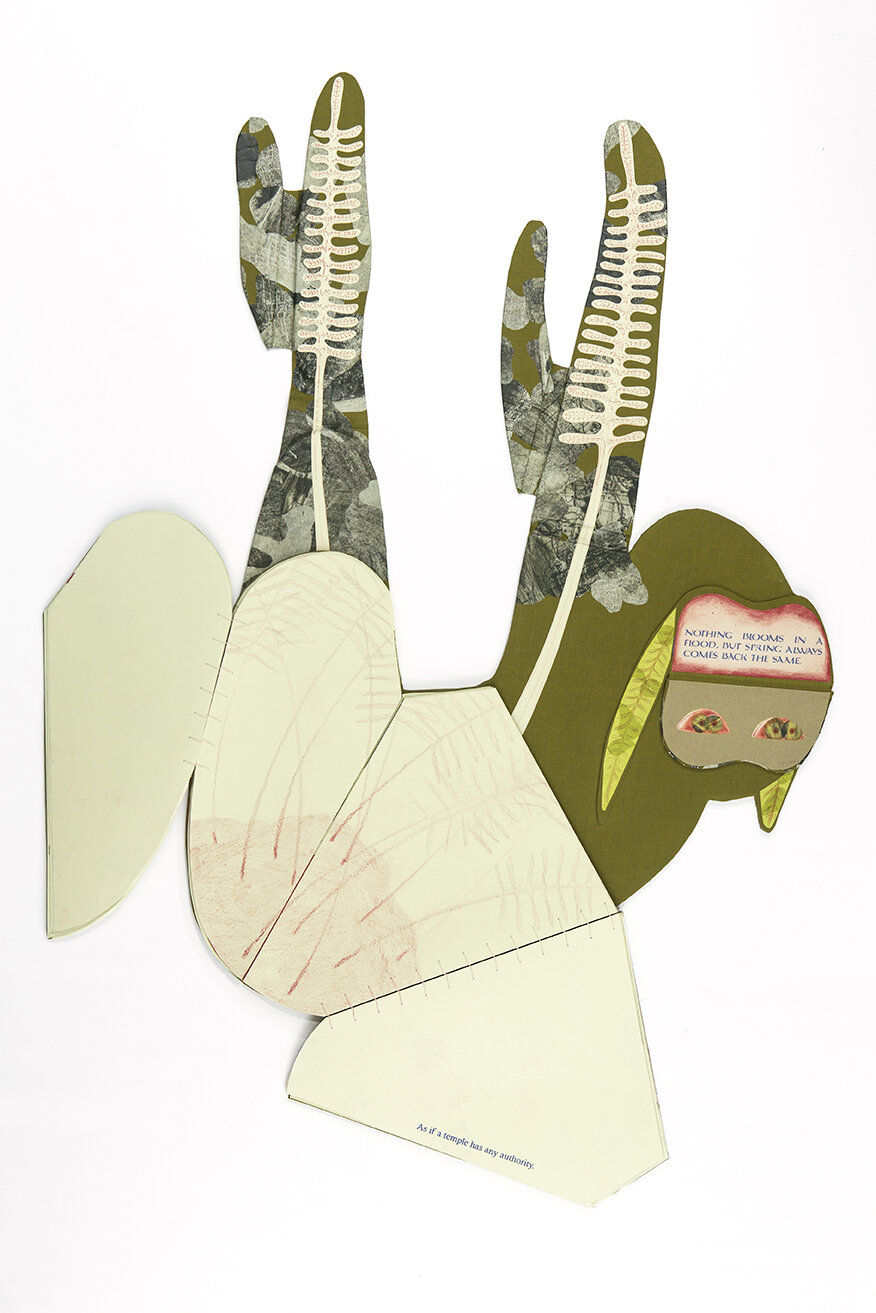

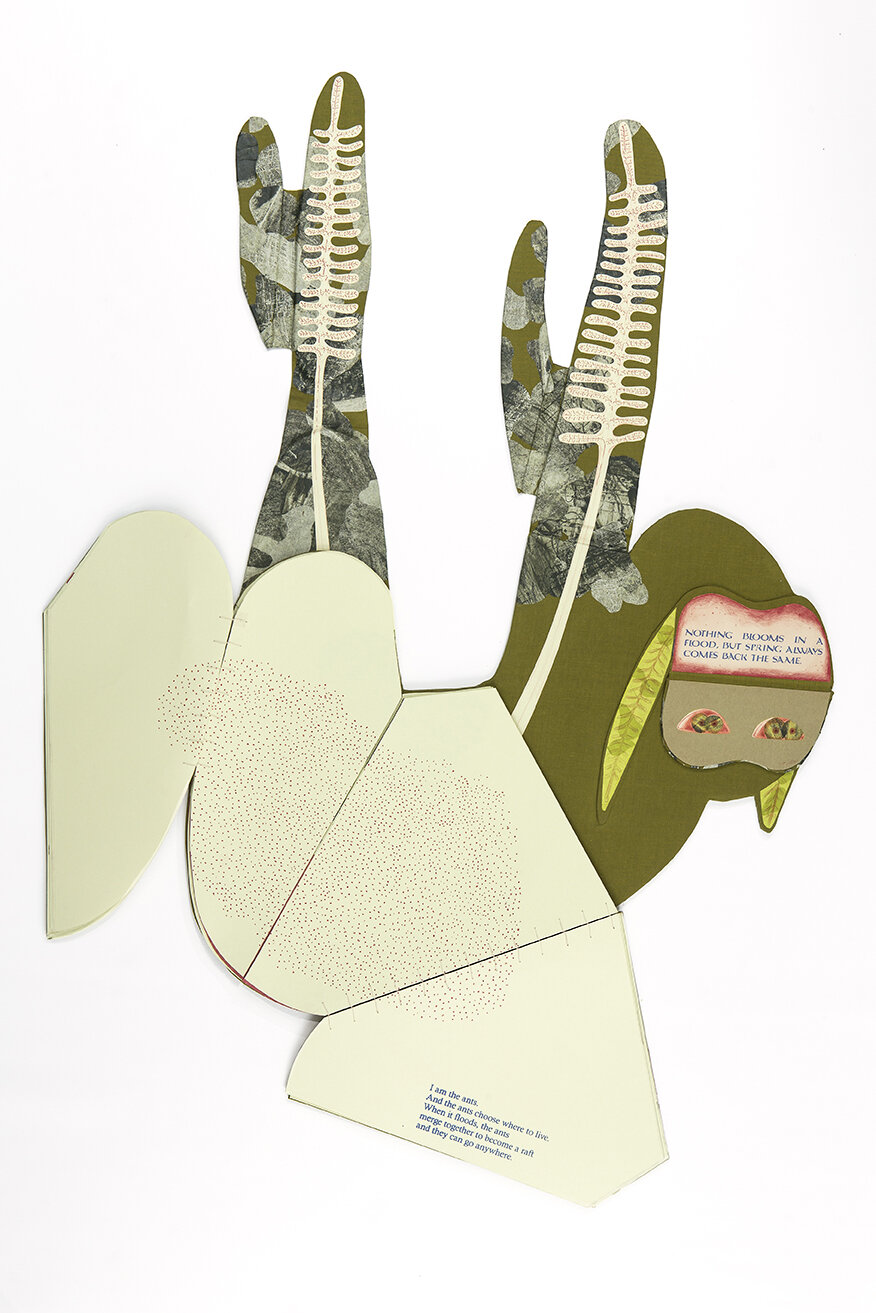

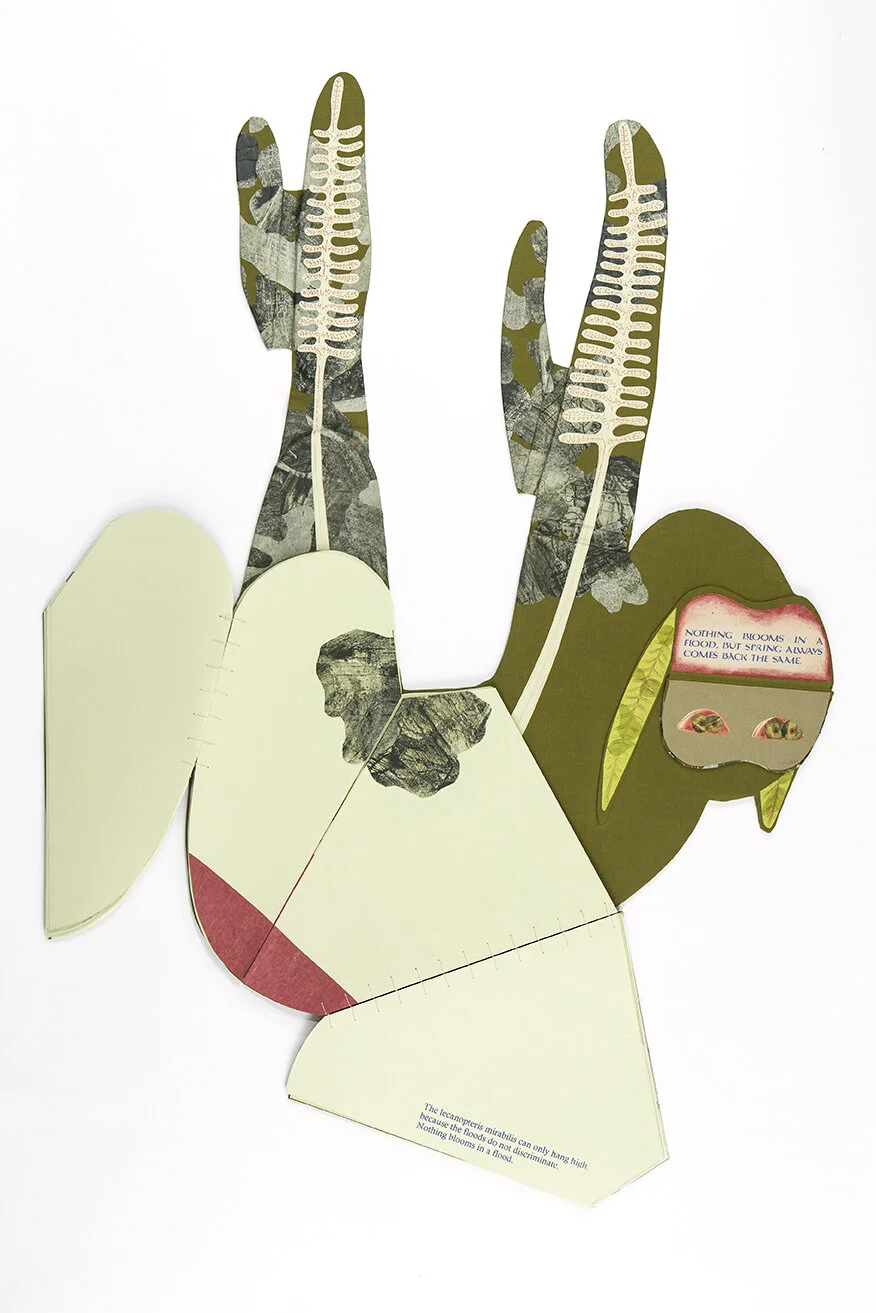

Lecanopteris Mirabilis

Nothing blooms in a flood, but spring always comes back the same.

Why ask my generation?

As is the generation of leaves, so is that of humanity.

The wind scatters the leaves on the ground, but the live timber

burgeons with leaves again in the season of spring returning.

So one generation of men will grow while another

dies.

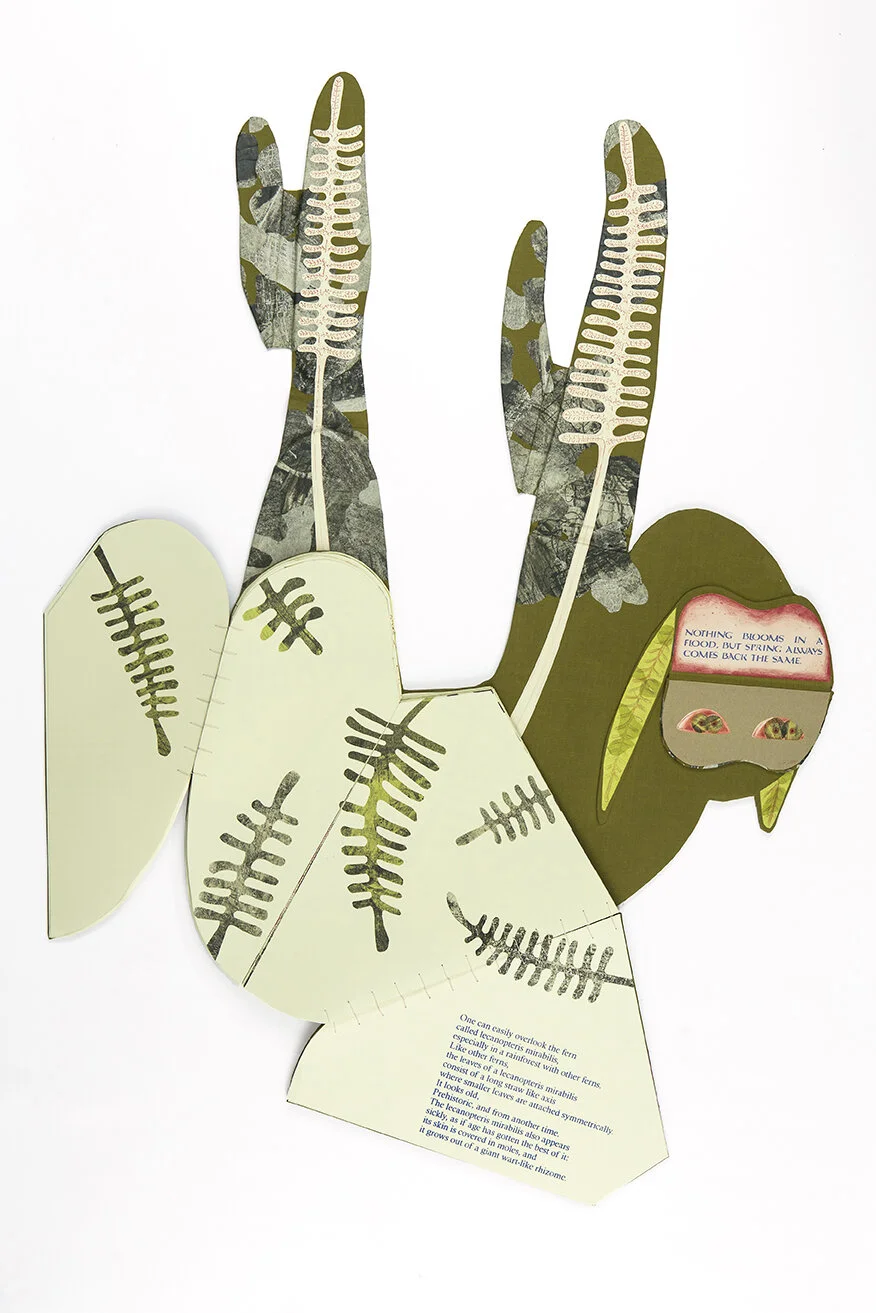

One can easily overlook the fern

called lecanopteris mirabilis,

especially in a rainforest with other ferns.

Like other ferns,

the leaves of a lecanopteris mirabilis

consist of a long straw like axis

where smaller leaves are attached symmetrically.

It looks old,

Prehistoric, and from another time.

The lecanopteris mirabilis also appears

sickly, as if age has gotten the best of it:

its skin is covered in moles, and

it grows out of a giant wart-like rhizome.

The lecanopteris mirabilis is old,

prehistoric, and from another time,

it is Philemon and Baucis who

offered me shelter a long,

long time ago.

There was a day

when Zeus and I disguised ourselves

as mortals; I was his son.

We sought shelter from thousands of homes, all of which refused us until

we came to the home of poor

old Philemon and Baucis.

They hosted us with

cabbage from the garden, smoked bacon,

green and black olives,

endive and radishes,

cream cheese, eggs, nuts,

dried dates, plum, fragrant apples,

and purple grapes.

The wine kept welling up in

the mixing bowl all by itself,

but this was our doing.

Pious Baucis and sweet Philemon were

embarrassed by the phenomenon and

wanted to kill

their only goose for us to eat.

They tried to catch the animal, but

their frail bodies could not move fast enough.

We told them to just let the goose live;

spring was coming.

Zeus and I told Philemon and Baucis to

climb to the highest point that they could,

so that we could punish the

thousands of people who did not shelter us.

The old couple did as we told, and

when they turned around they saw

everything covered with water,

except for their house.

They heard the cries of

mothers wailing,

and some patches of water

turned a pomegranate color.

What was their small house,

we turned into a temple and

Zeus granted them one wish.

They wished to spend their lives together in

harmony.

They took care of the temple and

one day their wish came true.

Philemon saw Baucis, and

Baucis saw Philemon

sprout.

The moles on her skin became spores

as her face split into bundles of leaves,

her hair twisting into long shoots.

The warts on his body merged

into one

as his body collapsed into lumps

of woody material.

They became the lecanopteris mirabilis,

the epiphyte that clings onto

the large trunks of trees

by its roots.

Philemon became the rhizome,

and Baucis became the fern leaves.

If you were to see one in the rainforest,

you might notice that

there are ants crawling all over this plant.

That is because the lecanopteris mirabilis and

the ants share a mutual relationship.

Inside the rhizome of the lecanopteris mirabilis

are tunnels, cool coiling tunnels

for the ants to thrive.

The tunnels keep evolving because

the ants continue to crawl all over

the intricate body of the lecanopteris mirabilis

making it unattractive to herbivores.

The lecanopteris mirabilis trusts the ants

but if the ants cheat the relationship

by not showing their fleshy bodies to

hungry butterflies and parrots,

it can stop growing the nutritious tunnels.

detail

Foolish leaves.

As if a temple has any authority.

I am the ants.

And the ants choose where to live.

When it floods, the ants

merge together to become a raft

and they can go anywhere.

The lecanopteris mirabilis can only hang high,

because the floods do not discriminate.

Nothing blooms in a flood.

Philemon and Baucis can only hang high,

because the floods do not discriminate.

Nothing blooms in a flood.

If an epiphyte thrives in an environment,

there is no need for

sexual reproduction—the production of

an individual.

Vegetative reproduction—the production of

a clone, is preferable

as it maintains the harmony with the habitat.

The population stays strong; it becomes a

biomass of genetically identical organisms physically

separate in every way.

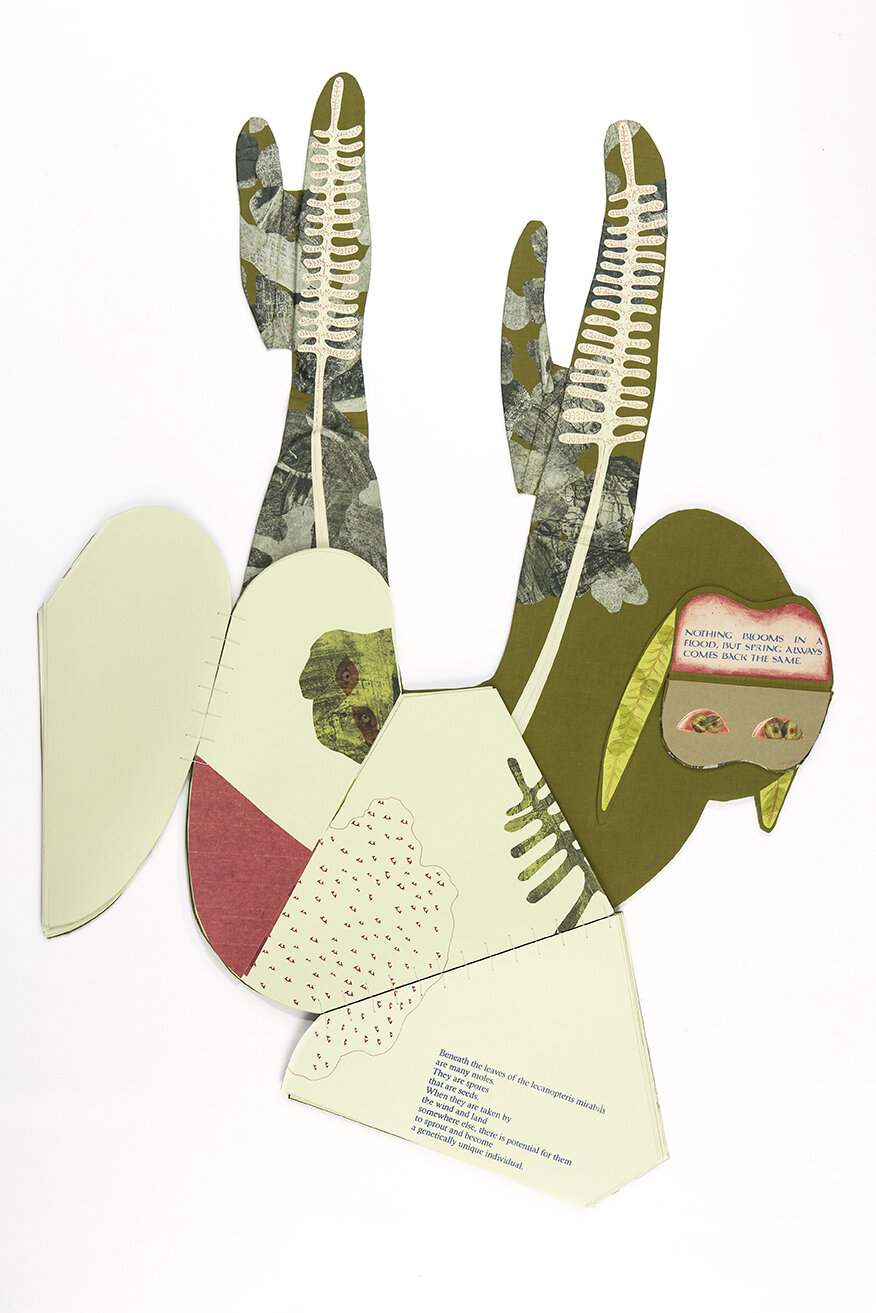

Beneath the leaves of the lecanopteris mirabilis

are many moles.

They are spores

that are seeds.

When they are taken by

the wind and land

somewhere else, there is potential for them

to sprout and become

a genetically unique individual.

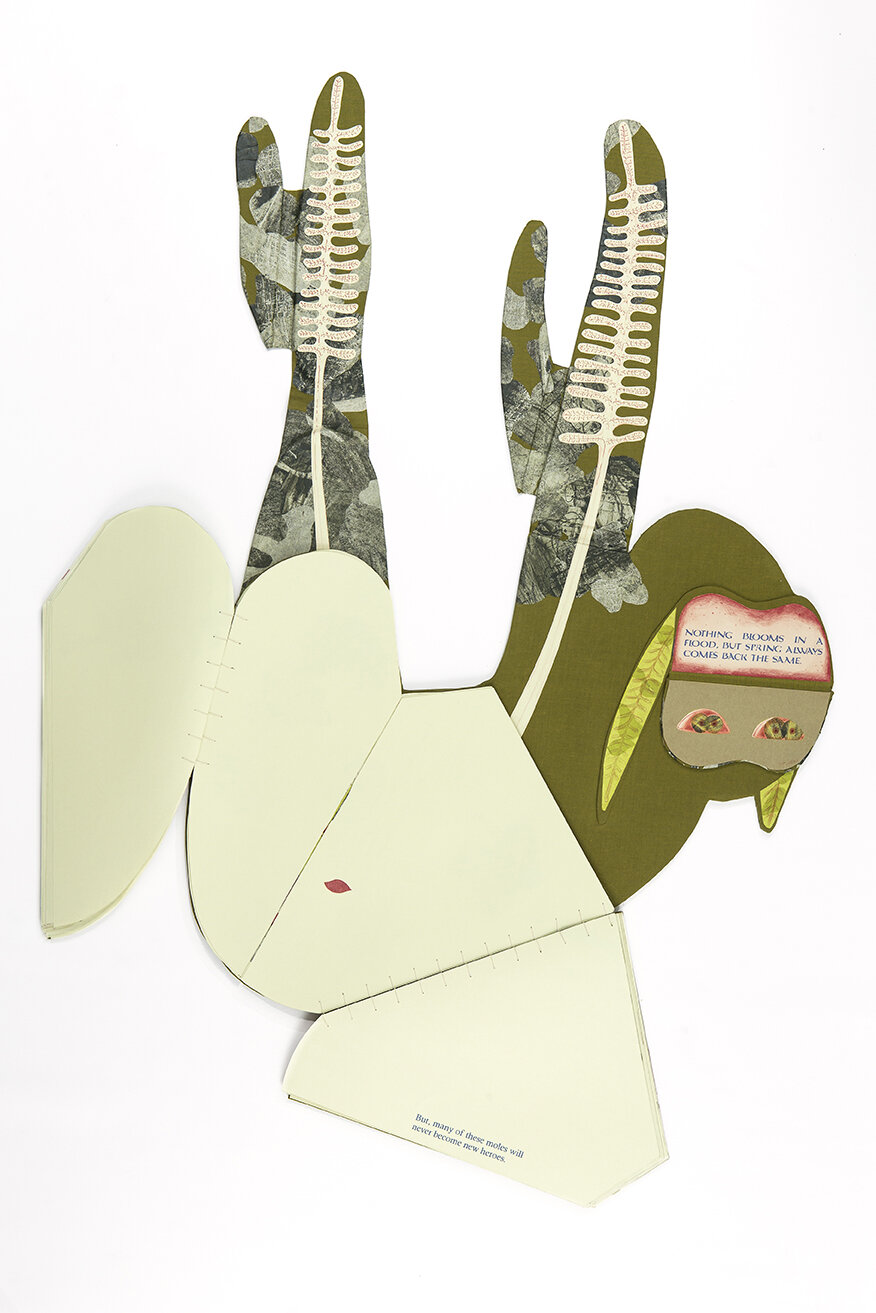

But, many of these moles will

never become new heroes.

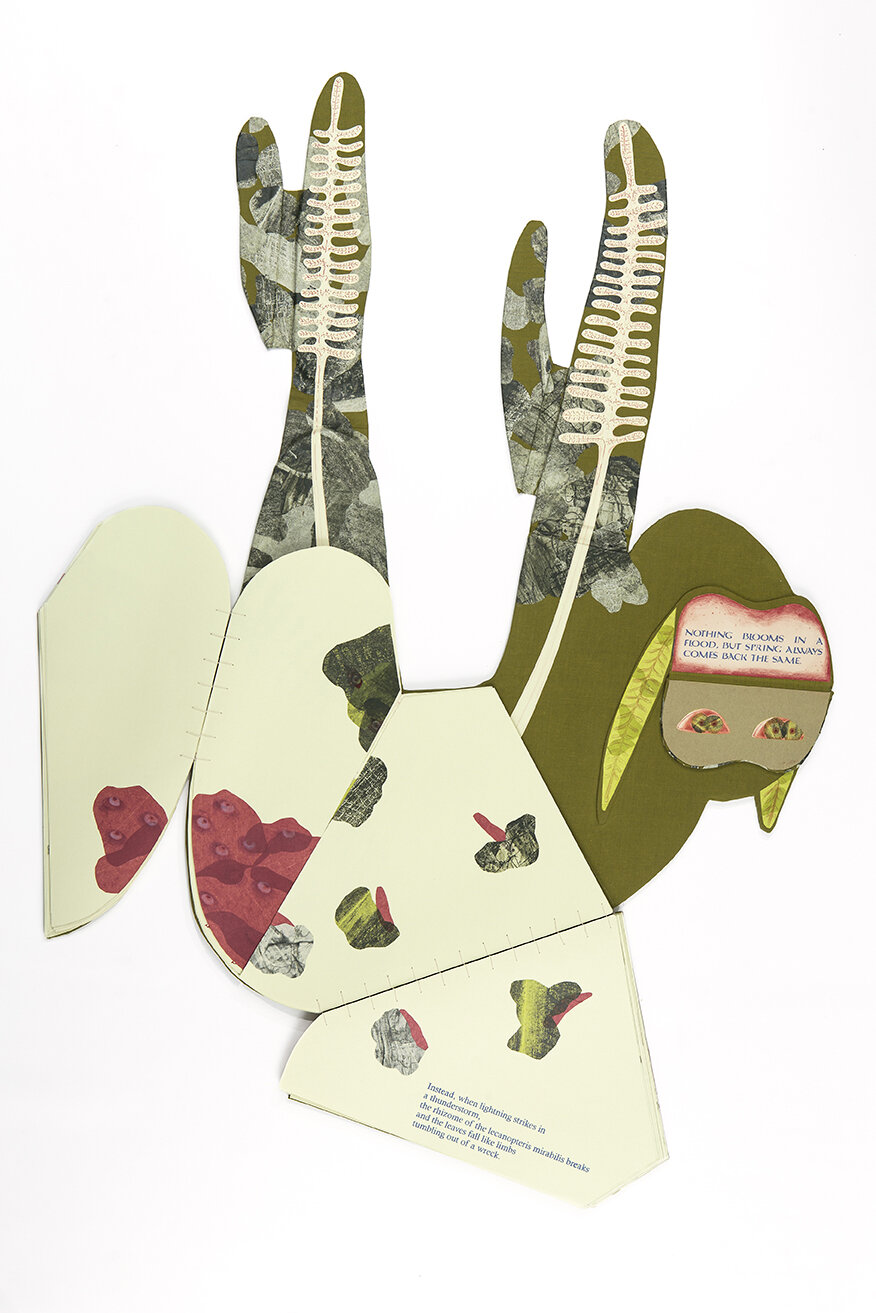

Instead, when lightning strikes in

a thunderstorm,

the rhizome of the lecanopteris mirabilis breaks

and the leaves fall like limbs

tumbling out of a wreck.

After the storm,

after the flood,

and after the separate chunks of plant

land on nearby host trees,

they will sprout.

They will sprout Philemon and Baucis

again, and again.

Rhipsalis Ramulosa

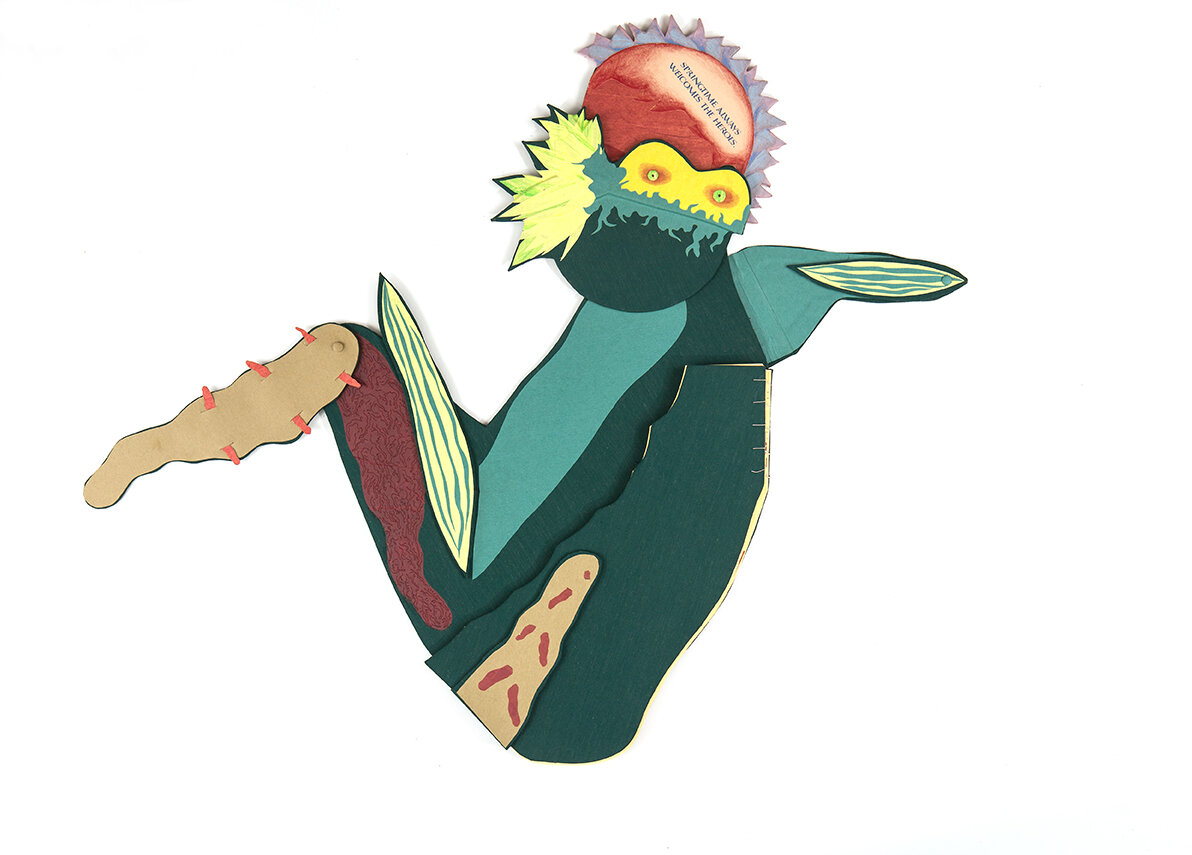

Springtime always welcomes the heroes.

Why ask my generation?

As is the generation of leaves, so is that of humanity.

The wind scatters the leaves on the ground, but the live timber

burgeons with leaves again in the season of spring returning.

So one generation of men will grow while another

dies.

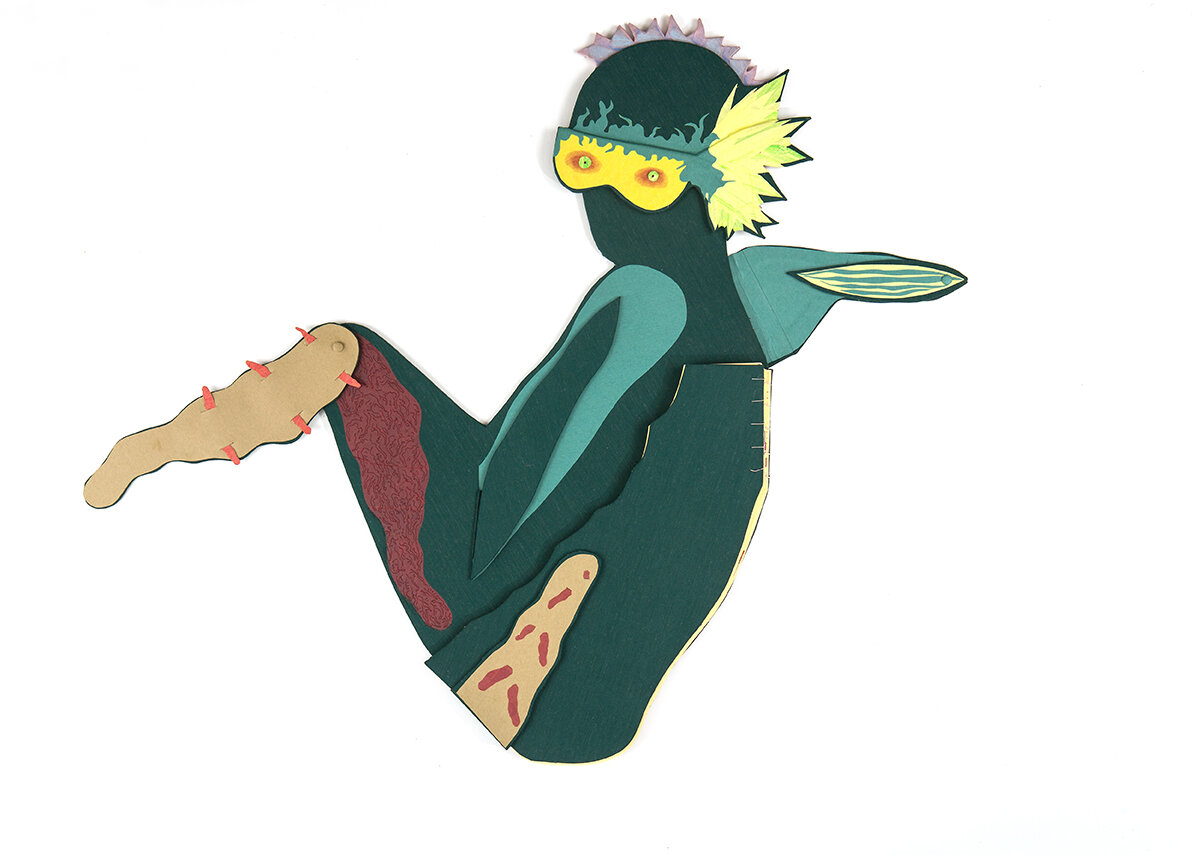

detail

If you are in Central America,

you might see a rhipsalis ramulosa,

but it shouldn’t be there,

it shouldn’t exist.

You see, the genus Rhipsalis

are cacti and cacti are

originally from North America.

A long time ago, a bird traveled

from present day Tuscan to Managua,

and carried a cactus fruit seed

inside of its stomach.

The bird found rest on the bed

of a tropical forest,

where it released the seed into the soil.

The likelihood of this

seed sprouting,

never mind surviving,

was slim to none. However,

on this rare occasion,

a mutant cactus emerged,

and it found the dense air ideal

for a new life.

detail

This cactus is the rhipsalis ramulosa,

the epiphyte that clings onto

the large trunks of trees

by its roots.

Each leaf is long and ovular,

they have the thickness of an ear lobe,

and the redness of blushed cheeks.

Each leaf has a long flexible stem,

which connects it to the next leaf.

Each leaf is healthy and heavy,

making the plant droop

as it climbs around the forest.

Many people call this plant

the devil’s tongue.

But these are hanging tongues of Persephone

who was taken from her mother and

raped by Hades.

detail

Demeter,

the goddess of harvest and

Persephone’s mother,

remembers that day when

a sharp pain gripped her heart, and

her seedling was taken away from her.

None of the birds flying

between Tuscan and Managua

came to her as a truthful messenger.

Demeter had

lost her immortal daughter,

and as Persephone

bled in the underworld,

her mother wailed.

To make up for the loss of Persephone,

Demeter thought that if she could raise

a boy into a hero,

immortal and ageless forever.

But men are too foolish

to know ahead of time

the measure of good and evil

which is yet to come and

it is not possible for him to

escape the fate of death.

Her failure turned into rage,

the goddess of harvest left

the earth barren, and

she contemplated a great scheme to destroy

the feeble races of earth-born men.

Zeus needed to prevent this and

commanded Hades to return his

beloved Persephone to her mother.

However, Hades offered Persephone to

eat a honey-sweet pomegranate seed.

The seeds of the rhipsalis ramulosa

grow on the edges of the

tongue-shaped leaf.

They are kept inside

white iridescent round pearls that look

like pomegranate seeds that have

lost their blood.

Demeter suspected trickery when

she embraced the return of her Persephone.

Sure enough, by Persephone

eating the pomegranate seeds,

she was not fully returned to her mother. Instead, she shall fly and

go to the depths of the earth

to dwell there a third of seasons in the year,

spending two season with her mother

and the other with immortals.

detail

Near present day Tuscan

where many of the cacti live,

the fruits bloom with

every kind of sweet-smell

in the season of spring.

Then when it is winter in Tuscan,

the white pomegranate seeds of

the rhipsalis ramulosa bloom with

every kind of sweet-smell

in Managua.

The bird found rest on the bed

of a tropical forest, where it

released the Persephone into the soil.

The likelihood of Persephone sprouting,

nevermind surviving,

was slim to none. However,

on this rare occasion,

a mutant Persephone emerged, and

she found the dense air ideal for

a new life.

Persephone is always the mistress

of the underworld and she always

goes back to her mother in the spring.

The rhipsalis ramulosa is the mistress

of Managua, and the same flowers bloom

in the Tuscan every spring.

The rhipsalis ramulosa only needed

to be a mutant once,

the one time Persephone was raped.

As an epiphyte, Persephone

does not want to relive Hades ravage,

so she does not spread her seeds.

detail

If an epiphyte

thrives in an environment,

there is no need for

sexual reproduction—the production of

an individual.

Vegetative reproduction—the production of

a clone, is preferable

as it maintains the harmony

with the habitat.

The population stays strong;

it becomes a biomass of

genetically identical organisms physically

separate in every way.

Persephone is one seed that clones.

The rhipsalis ramulosa clones.

Persephone’s tongues fall off and

become new sprouts.

The following essay was written for the occasion of the exhibition and catalog.

An Essay

by Bruce King

detail

Tammy Nguyen’s work reflects upon—and re-generates—one of the principal themes of archaic and classical Greek myth: the analogy—and dis-analogy—of the traditional hero to the ephemeral bloom of spring. The very word “hero” derives from the same Indo-European root as the word for “season,” particularly the season that is spring. From that vantage, the determinate quality of the hero’s life is to be “in bloom”; and heroic, especially Iliadic, myth often compares the culmination of the hero’s life—the moment when heroic desire and bodily force coalesce—to the bloom of a spring flower, though—crucially—that moment of surpassing strength and beauty is also the moment of death. The “beautiful death” of the hero—the emblem of which is the flower in bloom—arrives at the very pitch of masculine consummation; at that moment, life-form is both completed and destroyed. And at that same paradoxical moment, the hero’s life—his story—passes into the keeping of the epic bard: a death in exaltation on the battlefield assures the hero’s immortality in the songs of the traditional poet. The ephemerality of natural life is countered by immortality in the recitations, generation after generation, of the poets.

In the Iliadic speech that Nguyen cites in each of her re-imaginings of Greek myth, we hear the hero articulate—and grapple with—his own traditional form: mortal lives are as fleeting and insignificant as the leaves—or as nature itself, which cares nothing for the individual, only for the species; adopting, for the moment, the distanced perspective of the Olympian or the naturalist, the heroic speaker sees the insignificance of any particular human life. It is that threat of meaninglessness (or, that reality for Achilles) that catalyzes the logic of the “beautiful death”: the struggle of the hero is to rescue meaning, however uncertainly (and if only in death), from the annihilating turns and returns of the seasons, from the death-bound fragility of mortal nature itself.

In Nguyen’s retellings and visual re-graftings of Greek myth, the ancient tales are animated yet again, even as her foregrounding of a less familiar—less celebrated—nature contests the old insistence—the old tragic mania—on individuation, on adventure at all costs, and all for the story that follows. Epiphytes, rhizomes, clones, the harmonies of the biomass: the nature that Nguyen makes meaningful in her art speaks less of the struggle to press the individual name into collective consciousness than of the possibilities of other natures observed and celebrated, perhaps to our own evolving human good.

Bruce M. King (Ph.D., University of Chicago) teaches Classics and Humanities at the Gallatin School of Individualized Study, NYU and at the Pierrepont School. He has published on early Greek poetry and philosophy, on Attic tragedy, and on Freud. His book on the Iliad, Achilles All Unheroic, is forthcoming.