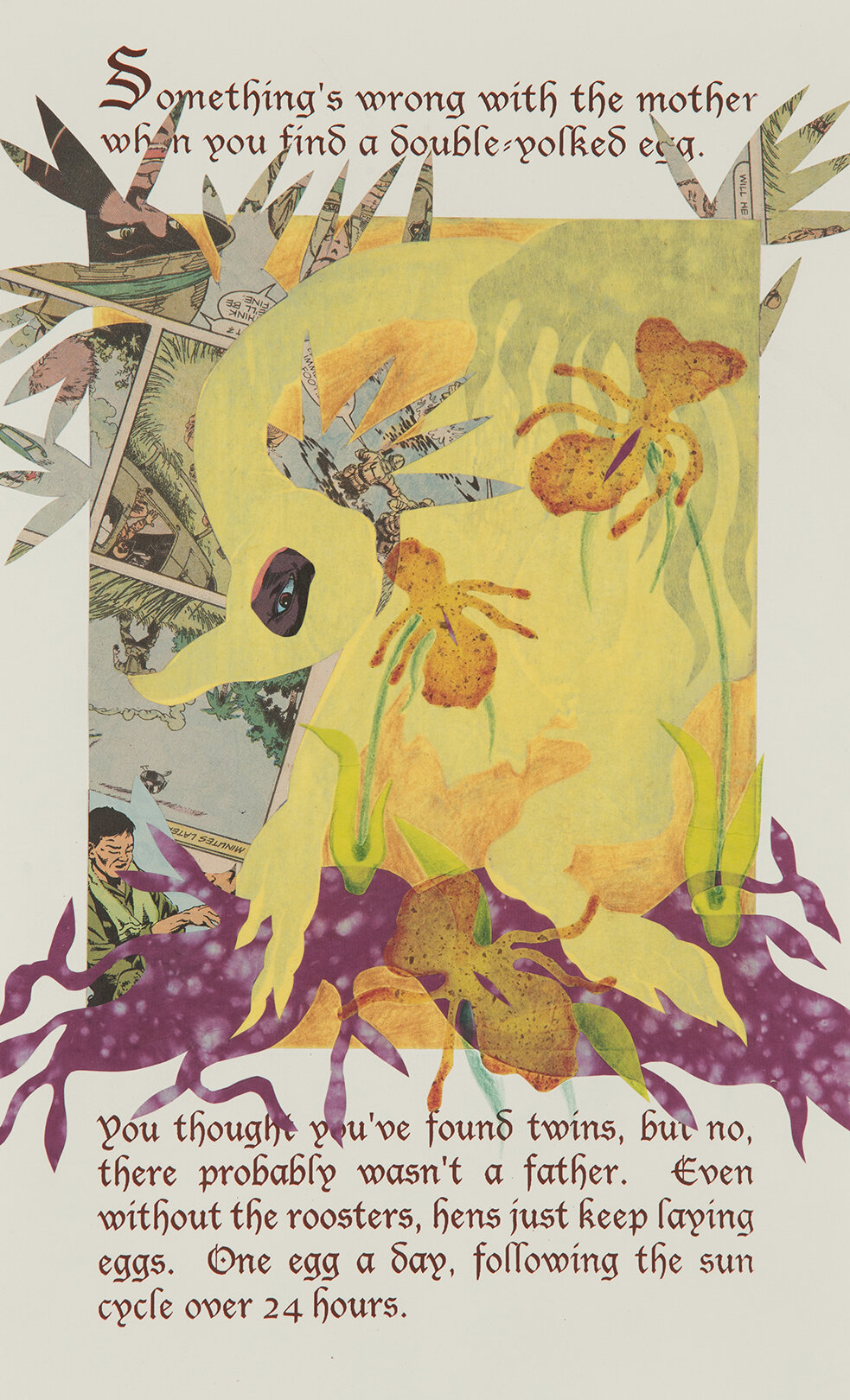

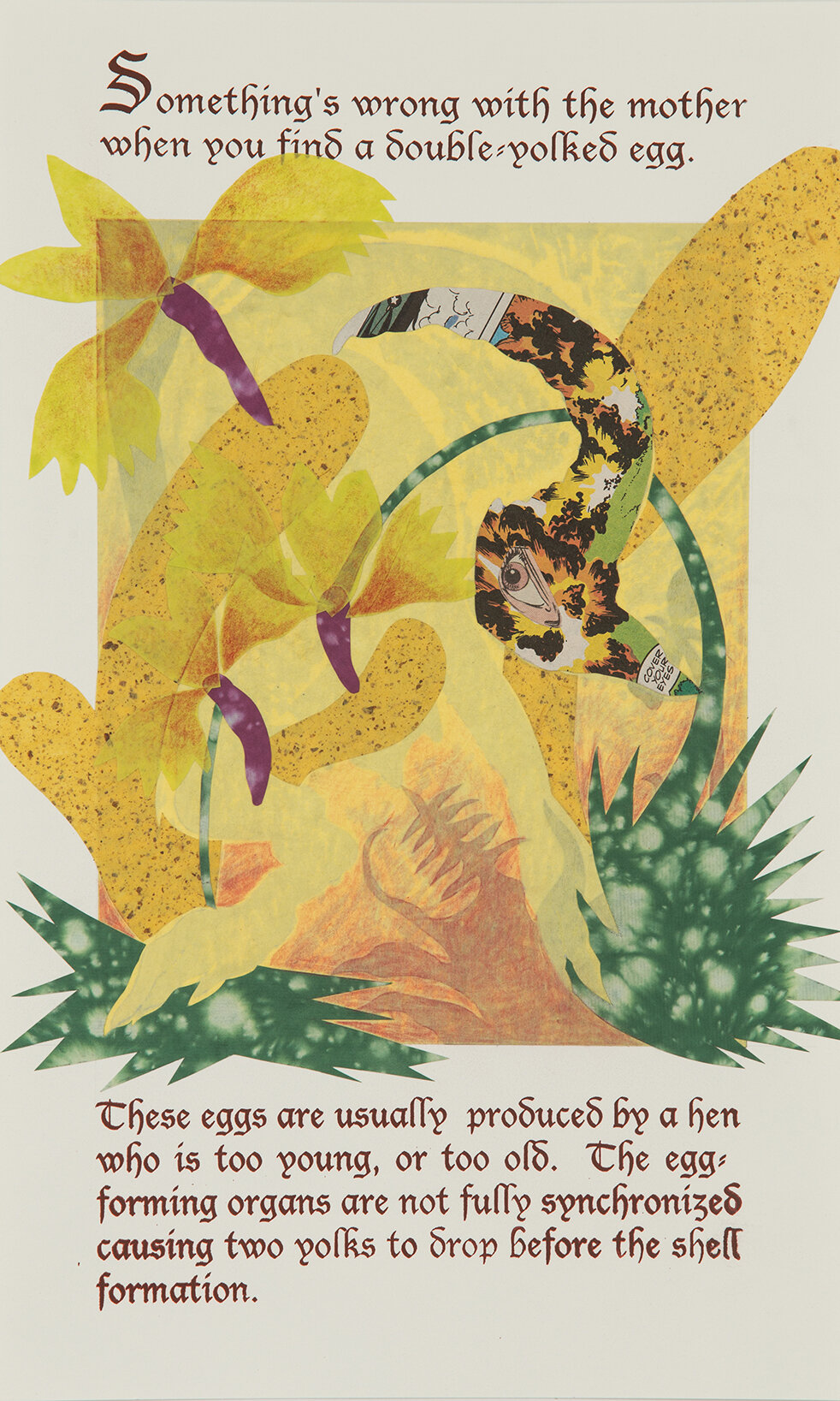

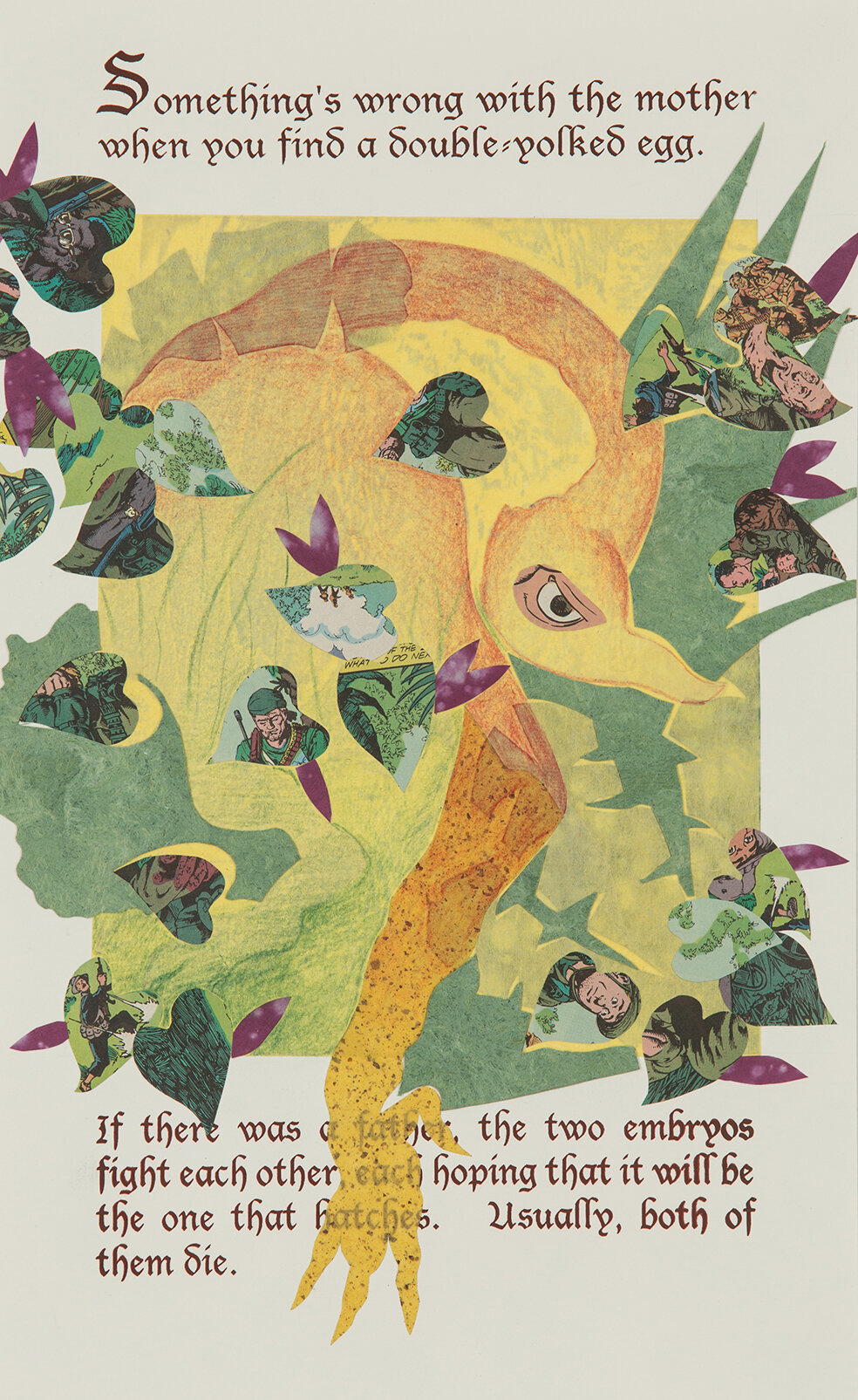

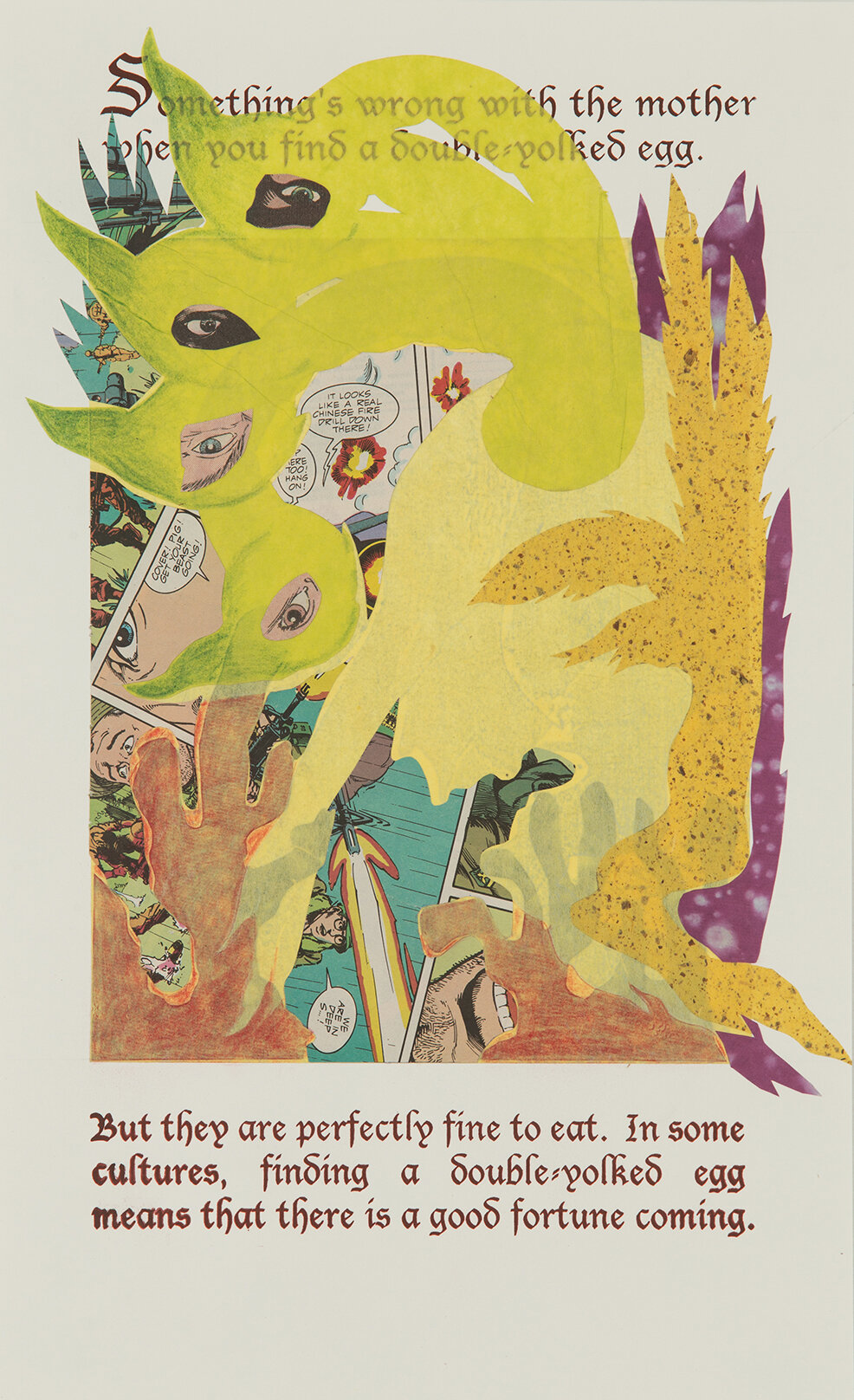

Chickens of the Torrid Summer

and other avian tales

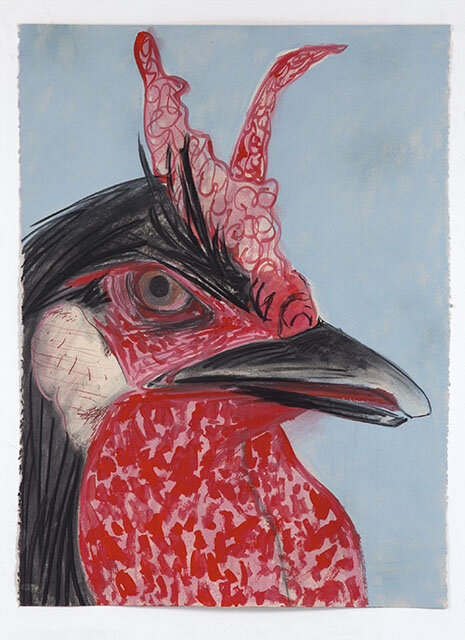

“Chickens of the Torrid Summer” was a solo exhibition at the Norwalk Community College in 2014. It was an exhibition of paintings and prints using the subject of chickens as a way to explore imaginations of the Vietnam War. The below writing was the catalog introduction.

Chicken

by James Prosek

There is a frenetic pace to Tammy Nguyen’s new body of work, and because a central theme is chickens, a popular saying comes to mind—like a ___________ with its head cut off.

As anyone who has witnessed the source of this expression, the chicken’s body continues to run around in all direc- tions without a brain to direct it—blood spurting as it goes. The spattered blood that springs from the still beating heart, in the absence of a head, is part of the expressionistic side of the art works in this visually arresting exhibition; whereas the representational side clearly says ‘chicken’ loud and clear. In the midst of the blood and the featherless chickens, there are cloudlike wisps of yellowed chicken fat and popping eyeballs that also resemble eggs with visible yolks as the eyes’ pupils.

So why chickens?

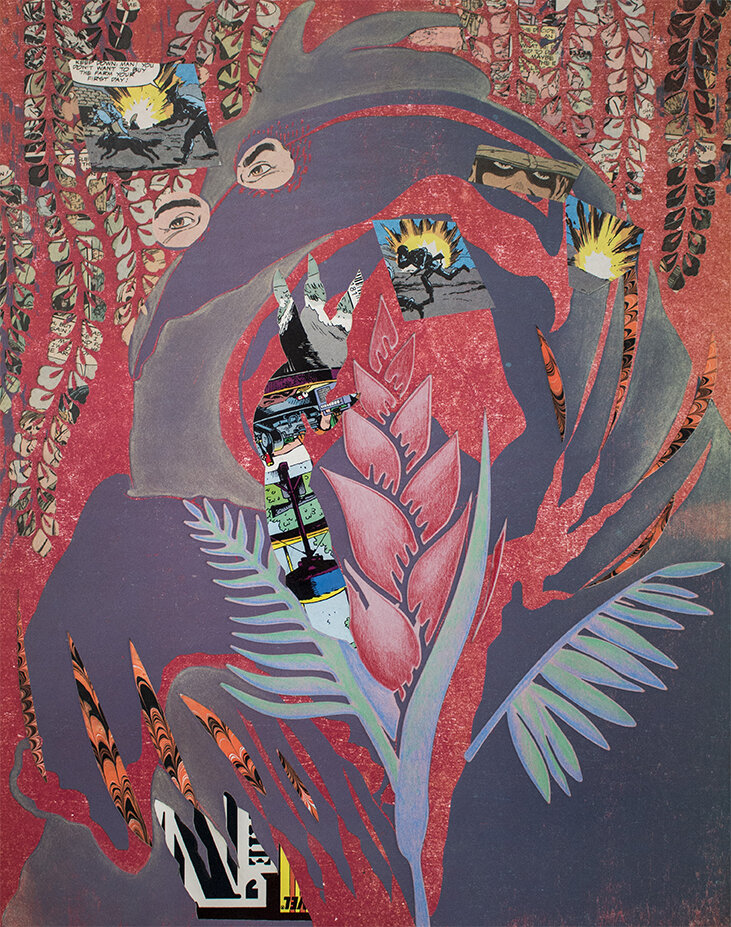

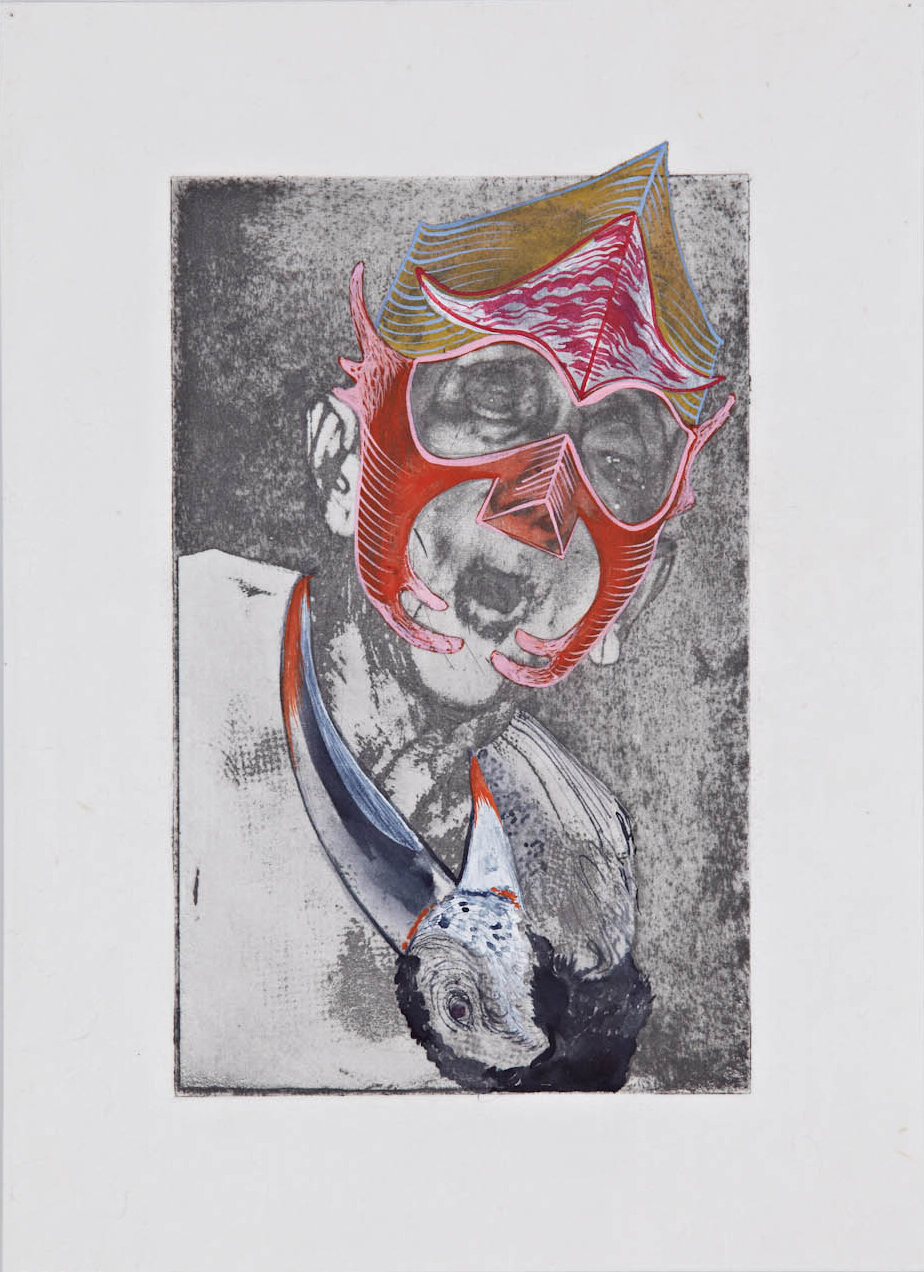

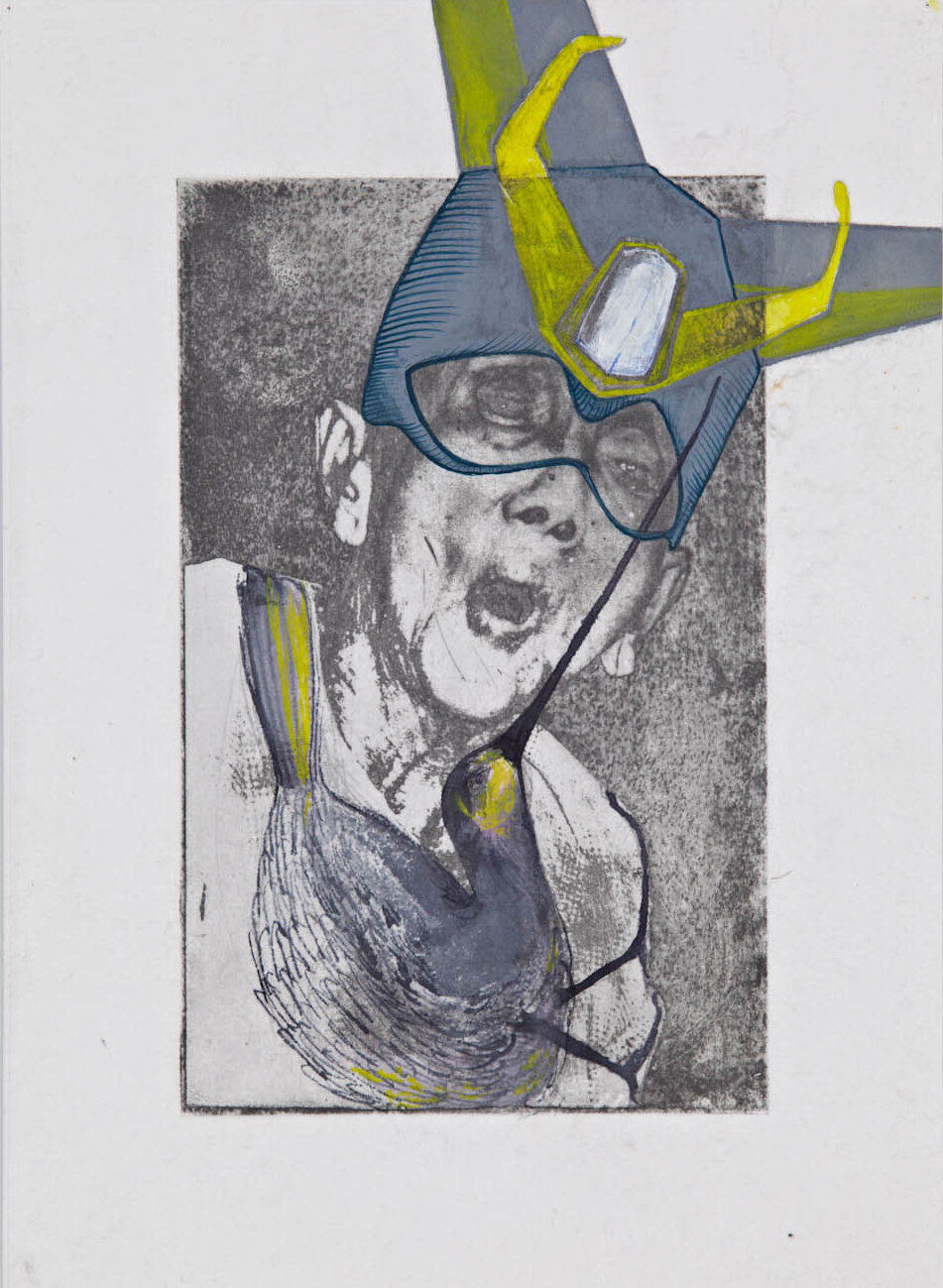

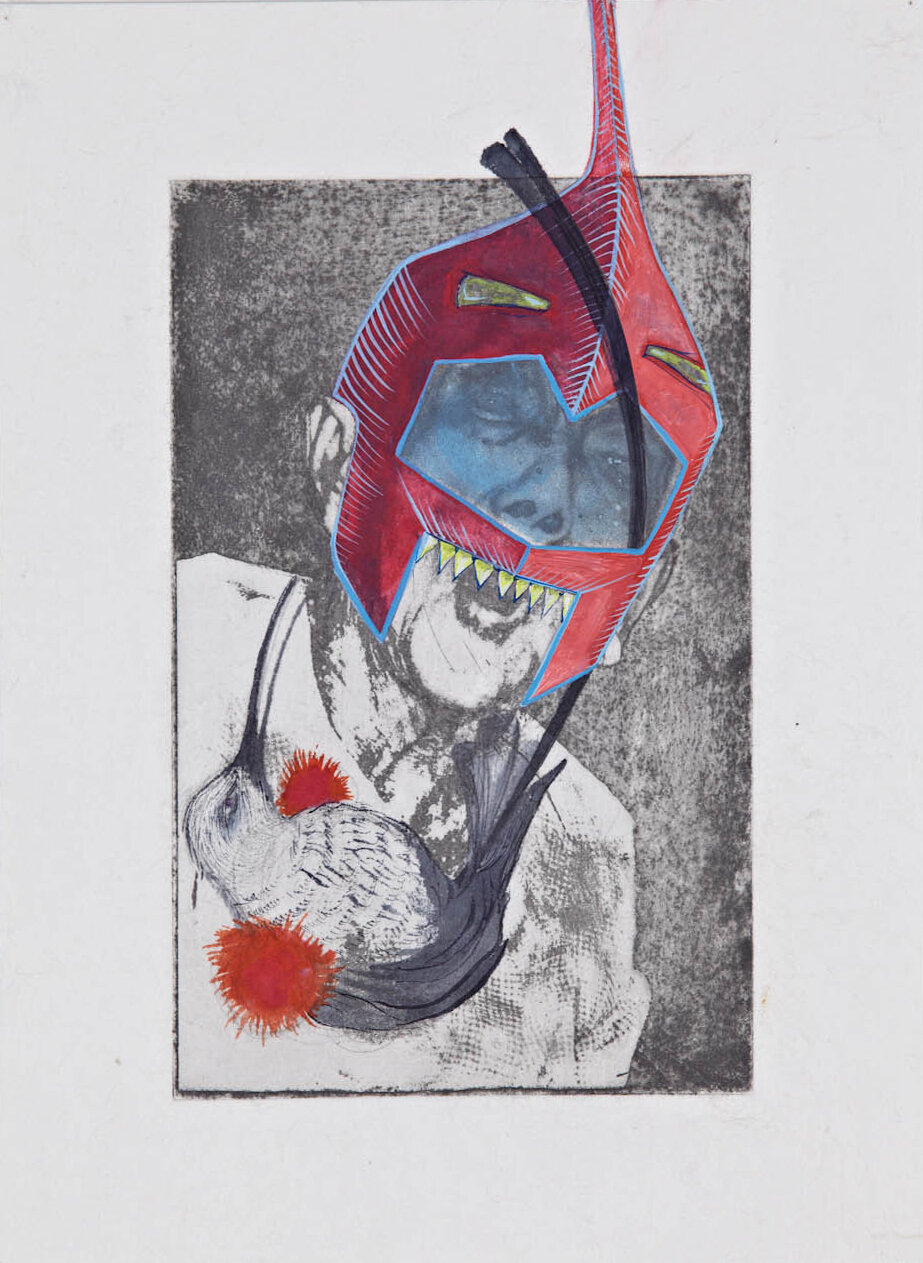

The Last Champion, 2014

There are deep and myriad cultural, political, and historical associations and issues we can extract including the domestication of wild animals (chickens were domesticated originally from Asian jungle cocks), the mistreatment of captive animals for our markets and sustenance, and ubiquity of the bird in third world Asia (Nguyen is of Viet- namese ancestry).

Nguyen’s first encounter with the chicken in its transition from living animal to food was at her friend’s restaurant in Ninh Binh, a northern mountain region of Vietnam. A woman in the kitchen was dipping a freshly killed chicken in hot boiling water. As she gently pulled the feathers off the bird she asked Nguyen if she was hungry. This was a vivid memory for Nguyen—witnessing the process of taking something’s life in order to sustain our own. Previously the intermediate steps between live chicken and food had been concealed. Here the continuum was visible. Nguyen began to think of other interstitial processes that lay hidden from our view—in birth and in war—and in her mind still associates them with this initial experience with the chicken.

To her soup of associations surrounding the chicken, both personal and universal, Nguyen adds cutouts from Viet- nam War era comic books. They are portraits of chickens arched in a tight composition (as if embryonic) trying to

gasp for air in a jungle where men in camouflage wait to ambush with guns. These soldiers are bearers of blood — an imaginary experience to Nguyen as she is an American-born daughter to Vietnamese refugees. Here, blood is realized through Nguyen’s appropriation of sensationalized imagery— like from a blockbuster movie.

Put all this in the hands of an accomplished painter and a master printmaker and you have something beautiful, strange, inexplicable, and bold. Each piece seems to strut off its stretcher bars or off the paper, filled with confidence but also agitation and a lot of nervous energy. The chicken is prey—who is waiting to take them out? What shad- ow is lurking over them? At what precise moment will they be hit or captured, and will feathers fly? As a viewer, personally, I start to feel part feathered cluck-er myself—is this the point? To remind us of the vulnerability of life?

Every viewer will be left to wonder while walking through the exhibition—why the chicken?—and will be left to search for an answer from their own set of experiences. Chances are we’ve all eaten one, and seen them both alive, racing along the ground or pecking—and dead, laying in shrink wrap or hanging in the market. Maybe we’ve even been awaken by one at dawn—their crowing marks the new day.

*

Artist, writer, naturalist, and Yale graduate James Prosek made his authorial debut at nineteen years of age with Trout: an Illustrated History (Alfred A. Knopf, 1996), which featured seventy of his watercolor paintings of the trout of North America. Prosek’s work have been shown The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA, The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, CT, The Addison Gallery of American Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, DC among others. Prosek has written for The New York Times and National Geographic Magazine and won a Peabody Award in 2003 for his documentary about traveling through England in the footsteps of Izaak Walton, the seventeenth-century author of The Compleat Angler.

curiously enough, Vol 2.

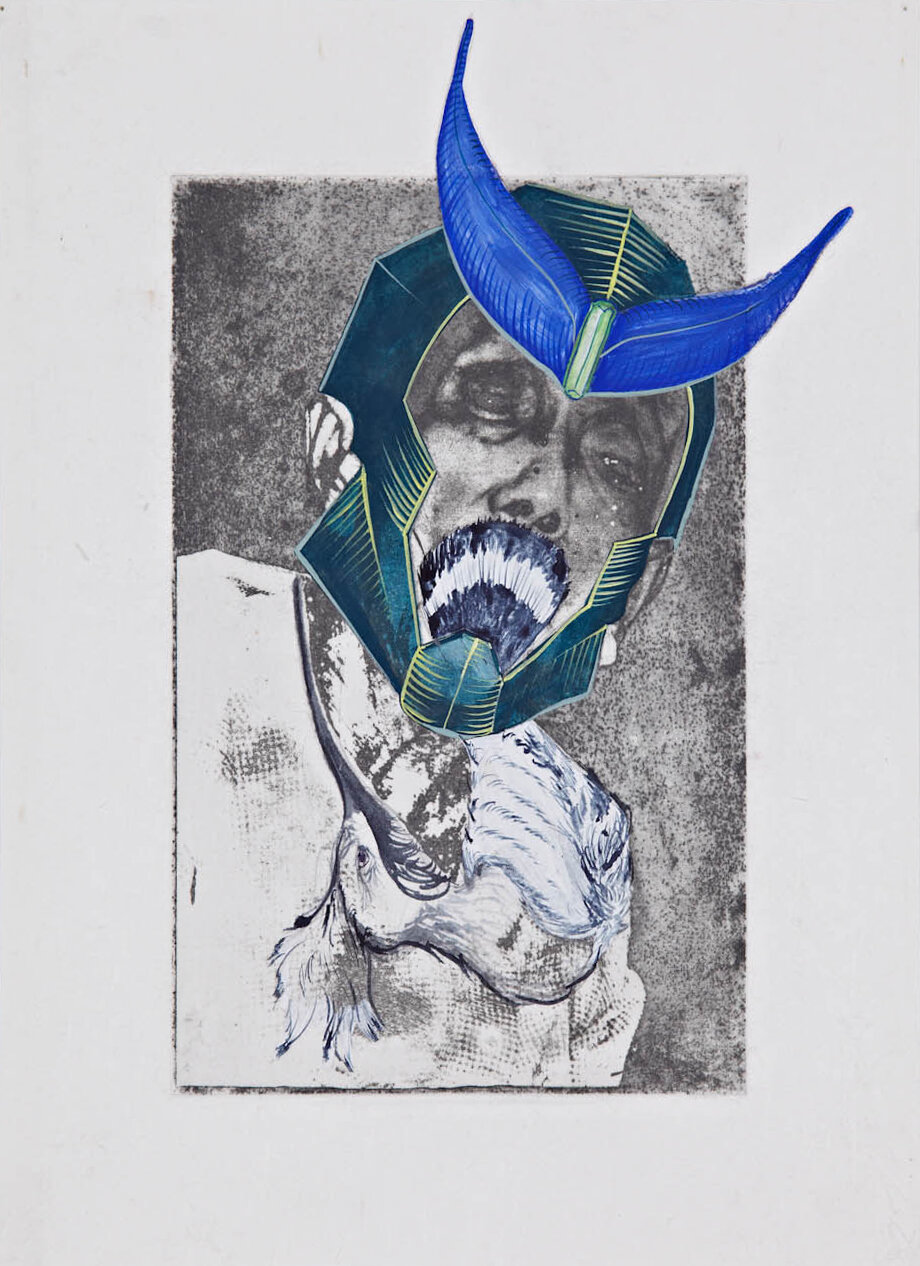

In Spring of 2019, I was invited by Galerie Nichido Taipei to continue my work from “Chickens of the Torrid Summer”. I created six woodblocks from the original key block in the Norwalk exhibition. Later in the Summer of the same year, the exhibition traveled to Tokyo, Japan to its sister gallery, Nichido Contemporary Art where I created two more paintings expanding the narrative into my more recent inquiries. Below is an artist statement included in the Japan exhibition as part of curiously enough, Vol 2. with Samak Kosem and Dusadee Pang Huntrakul.

Everything I know about the Vietnam War and everything that I don't is filled in with my imagination. Even as I continue to have experiences unrelated to my family's trauma, it is not uncommon for me to project fantasies of battle and bloodshed when I see such examples.

Two years ago, I witnessed several exhilarating cockfights in the area known as Pateros in Manila. The crowd was like a big cloud, raining in cheer and gambles. Scattered throughout the crowd were these men, known as the "Cristos" who were the bookies. They would wave their hands in the air like clockwork– one finger, two fingers, three fingers– to indicate what bets were being played. "Cristos", of course, also means "Christ"– so here we are witnessing a marathon of fights to the death and placing our bets with the One and only.

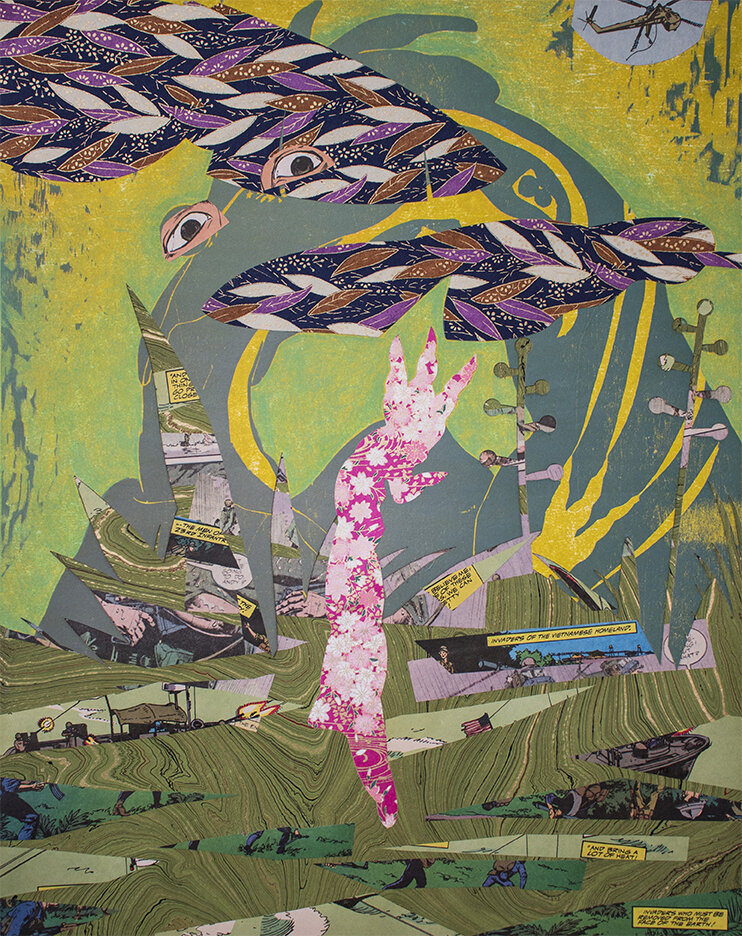

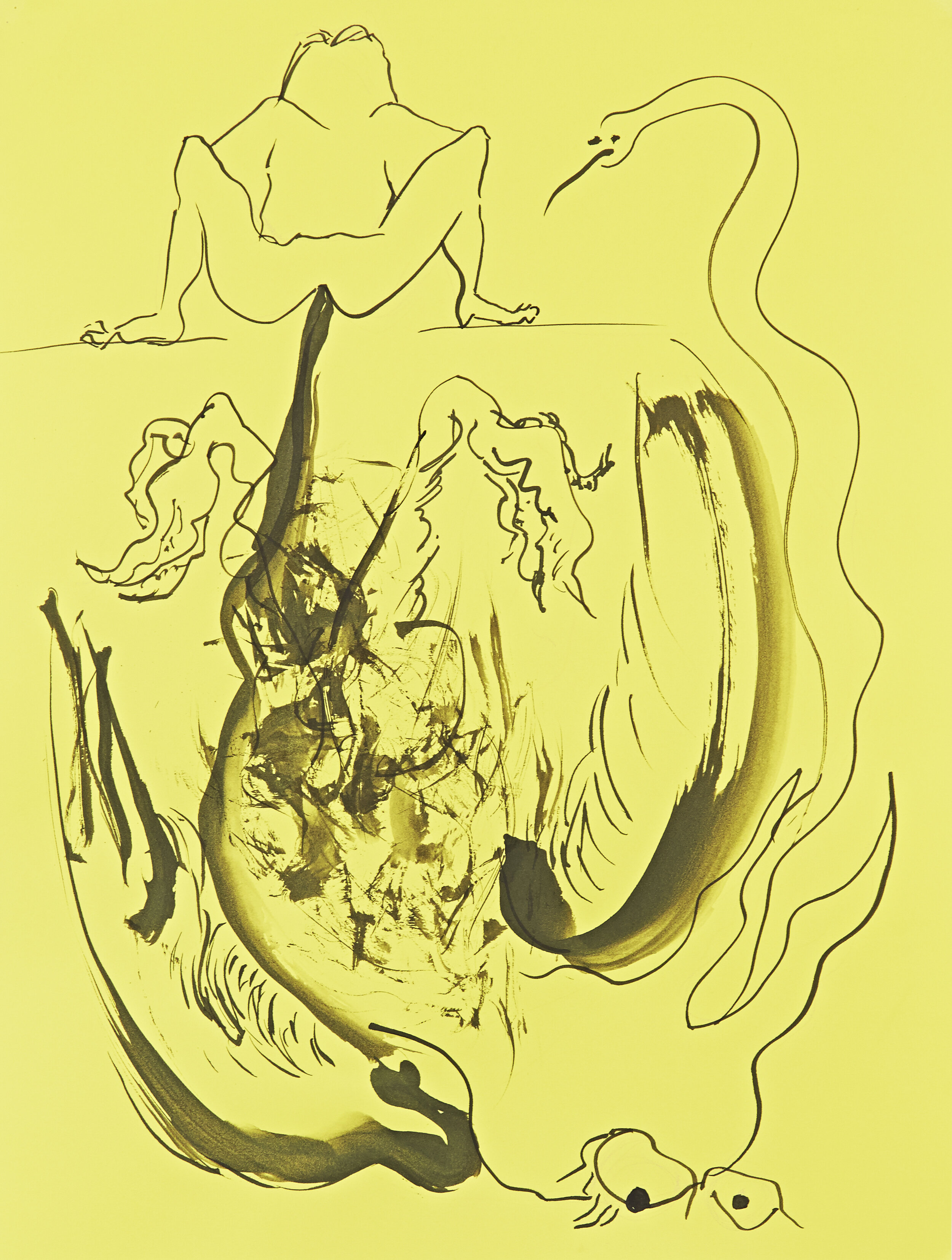

Landscape for the Cristos, 2019

Much of Apocalypse Now was shot in the Philippines, so there I was, my first time in Manila, heart full of excitement and anxiety as I watched the battle of chickens. I stretched my imagination (as Francis Ford Coppola did) and stretched it into this arena. The painting Coming of Grass in Pateros, depicts the climax of a cockfight when one chicken will win. But, as the cyclical qualities of war tend to be, this climax foreshadows the forthcoming of yet another battle– which is one way to think about the Vietnam War; while one war was fought, it is inevitable that another war will be fought again, but internally by the next generations to come, wherever those generations might be.

I happened to have been born and raised in San Francisco, and now I am fascinated with land. Last month, I visited the Phong Nha karst in Quang Binh Province, Vietnam for the first time and enjoyed a few small expeditions into caves millions of years old. On the way to one cave, our group needed to walk through a vast area of grass. Buffalo roamed peacefully, and there were these circular ditches and plateaus in the ground. I learned that this is how the dead from the nearby villages are buried and reburied. First, they are buried into these big circular ditches until the body disintegrates. Then, they are dug up and transferred into another grave next to older relatives.

For the occasion of curiously enough, Vol. 2, I thought about this circular ditch as the site where the bets have been buried, perhaps by the Cristos. The bets though, are not bets from cock fights as they have been metabolized through my imagination and turned into useless and memory-less accounts of the Vietnam War. The ditch featured in Landscape for the Cristos, is where these fantasies are buried.

This City of Jazz

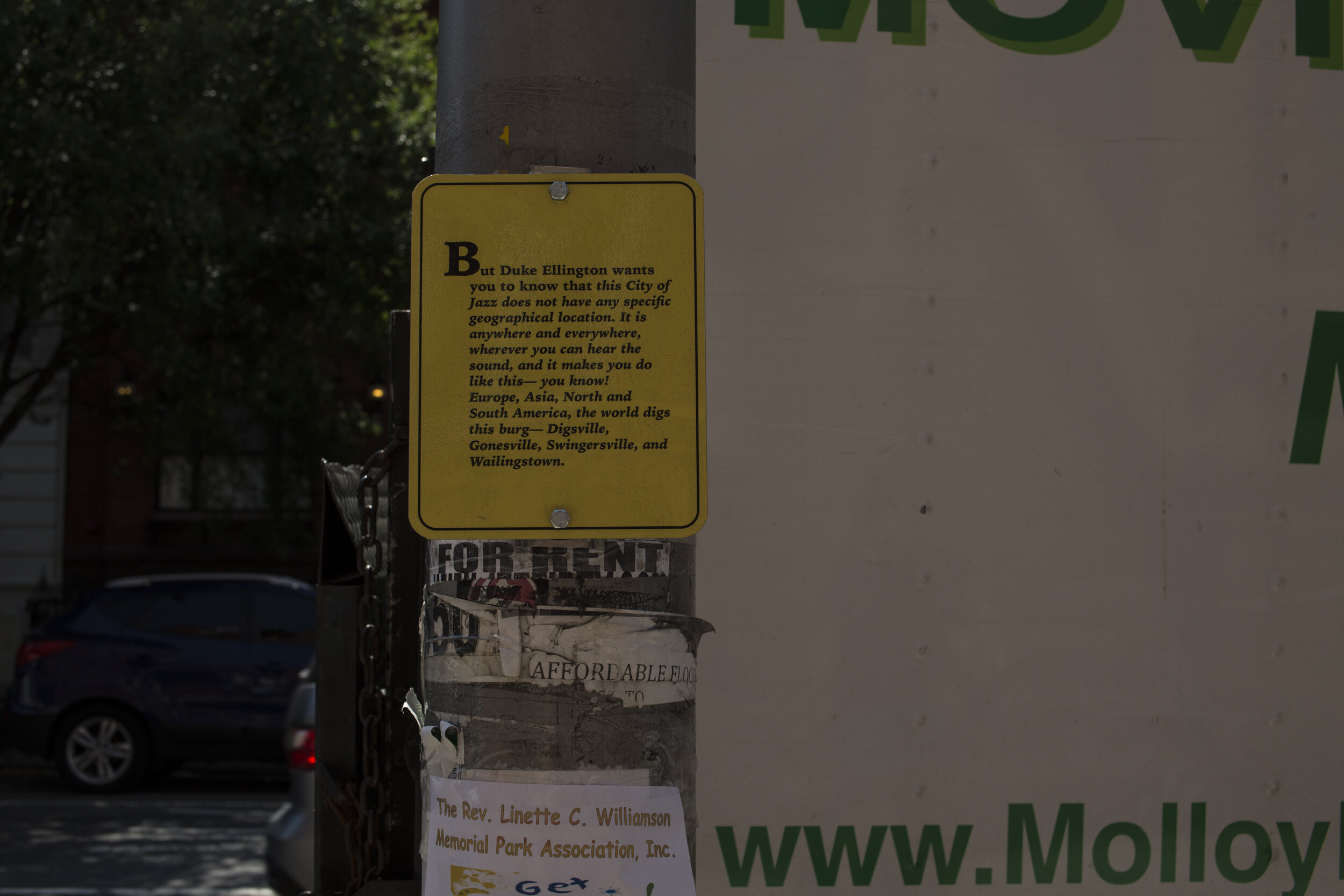

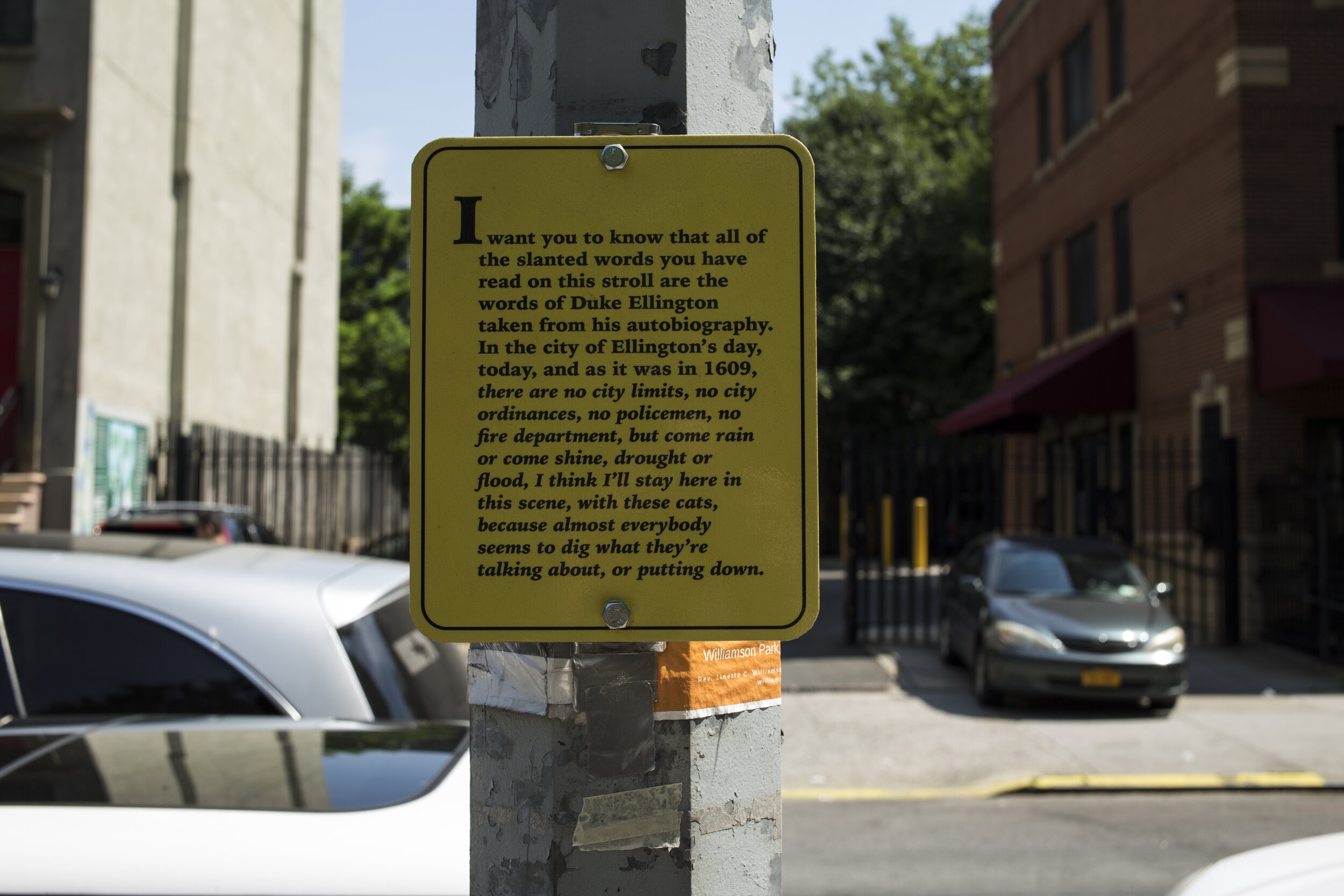

“This City of Jazz” was a public art work that started from the top of Marcus Garvey Park and ended at the American Jazz Museum in Harlem, NYC. Along the walk, viewers looked for banners featuring drawings of native birds and read a story about the avian species and jazz music. At the end of the walk, people could visit the museum and takeaway a newspaper with the story they had experienced.

This project was part of the Art in FLUX Fair in 2016 and was made possible with the generosity of the NYC Parks Department.

Map of the walk.

You are standing at the highest point in Harlem. From here you can see the whole neighborhood, the whole City of Jazz. Look around you and imagine that the buildings sink back into earth. The streets and sidewalks pick up their pavement and disappear. It is 1609. Henry Hudson hasn’t discovered the island of Manahatta yet. Listen: the sounds of the city are gone. There are no cars honking, or radios blasting, or people talking, shouting, laughing, or crying—all that jazz is gone. But it isn’t quiet. In fact, it’s pretty loud. Harlem is still the City of Jazz, only it’s a jazz of another kind. Listen: all around you, in every tree, the birds make music with chirps and hoots and shrieks and caws, the birds sing out their wild jazz.

In 1609, Harlem was a flat plain broken by two big lumps that used to be called Mt. Morris. You are making your way down Mt. Morris now, and the great big band of wild life is getting ready to play. Sweet juice oozes from the arched branches of black cherry trees. The spiky leaves of maples shake and shimmy in the wind while dark syrup slides down the trunk below.

This is how the jazz happens: Some of the birds are on their way out, while many others are on their way in. Some are rushing to get there, but others appear reluctant and are cautious in their approach. The bass starts with the blue-jay who flaps its wings then cries “jayer-jayer!” and flaps its wings faster and faster, applauding the crow who is about to take the stage.

“Caaw-caaw,” the big crow counts time for a new melody: “chick-a-dee-dee-dee, chick-a-dee-dee-dee,” the chickadee swings in and the crow laughs, “ki ki ki ki ki ki,” delighted.

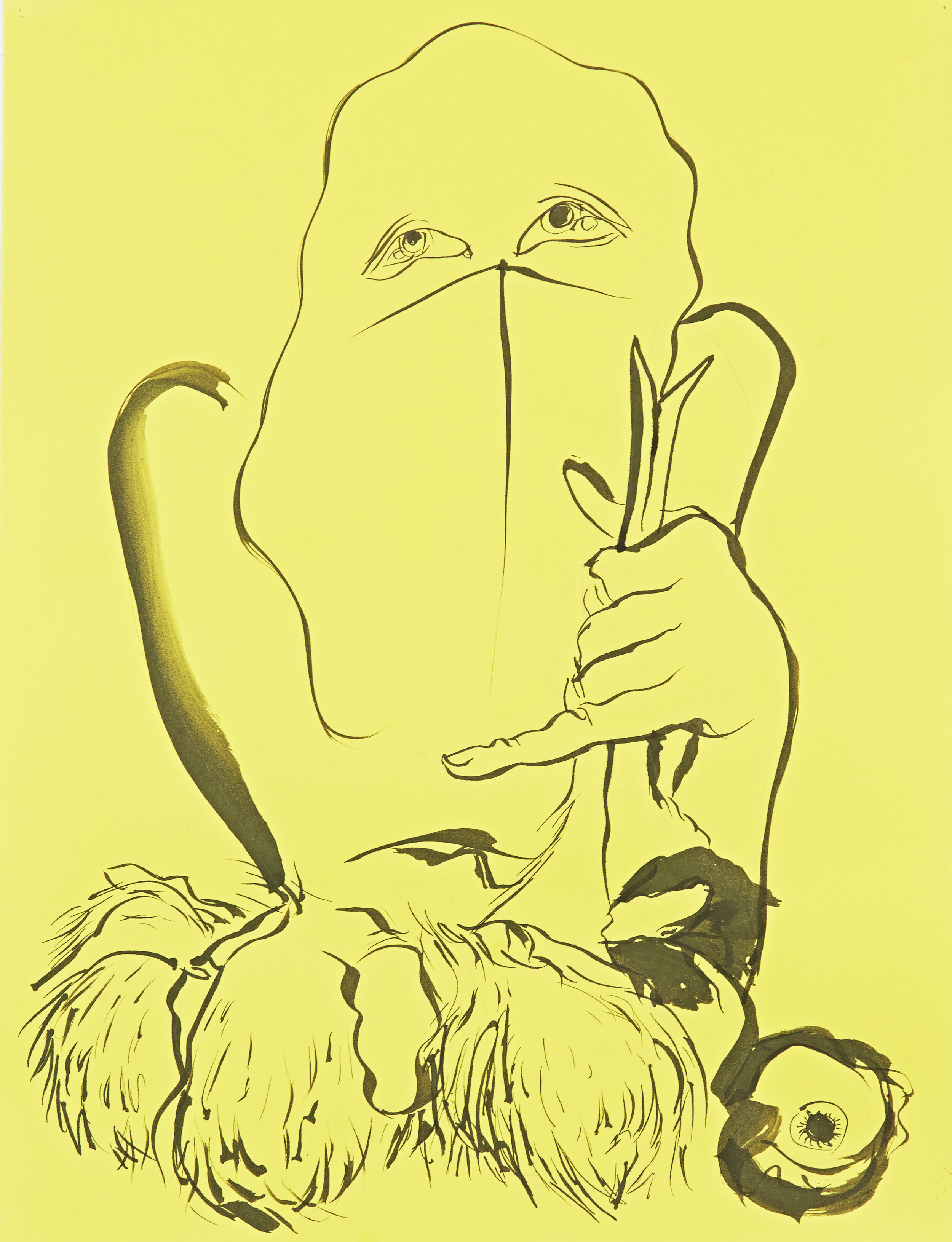

One of the banners.

Some birds claim they are afraid, and hesitate to expose themselves in this place where they feel so strange, this strange place where the most solid citizens are so hip or slick, or cool. The passenger pigeon tries to shy away, but its coos, twits, and clucks are a part of the jazz anyway.

My experience on many visits to and from the city (I do one-nighters, you know) has convinced me that its people are all very nice human beings. Even the red-tailed hawk, who is very unmusical. “Kree-eee-er! Guh-runk! Klee-uk!” its raspy scream rides the hard, the sharp, and the deep parts of the City of Jazz, from Mt. Morris’ long twisted spine of schist down to the rivers’ marble beds. “Kree-eee-er! Guh-runk! Klee-uk!”

The whole Harlem plain shivers with delight from this ornithology of noise. Vines creep up the legs of trees to hear better. Wild grasses continue to spread and spread, like wild grasses do. Everybody just utterly loses it when the thruster shrills, “eeew-ka ka ka ka.”

But Duke Ellington wants you to know that this City of Jazz does not have any specific geographical location. It is anywhere and everywhere, wherever you can hear the sound, and it makes you do like this— you know! Europe, Asia, North and South America, the world digs this burg— Digsville, Gonesville, Swingersville, and Wailingstown.

I want you to know that all of the italicized words you have read on this stroll are the words of Duke Ellington taken from his autobiography. In the city of Ellington’s day, today, and as it was in 1609, there are no city limits, no city ordinances, no policemen, no fire department, but come rain or come shine, drought or flood, I think I’ll stay here in this scene, with these cats, because almost everybody seems to dig what they’re talking about, or putting down.

As the birds sing out that wild jazz, they communicate, Dad.

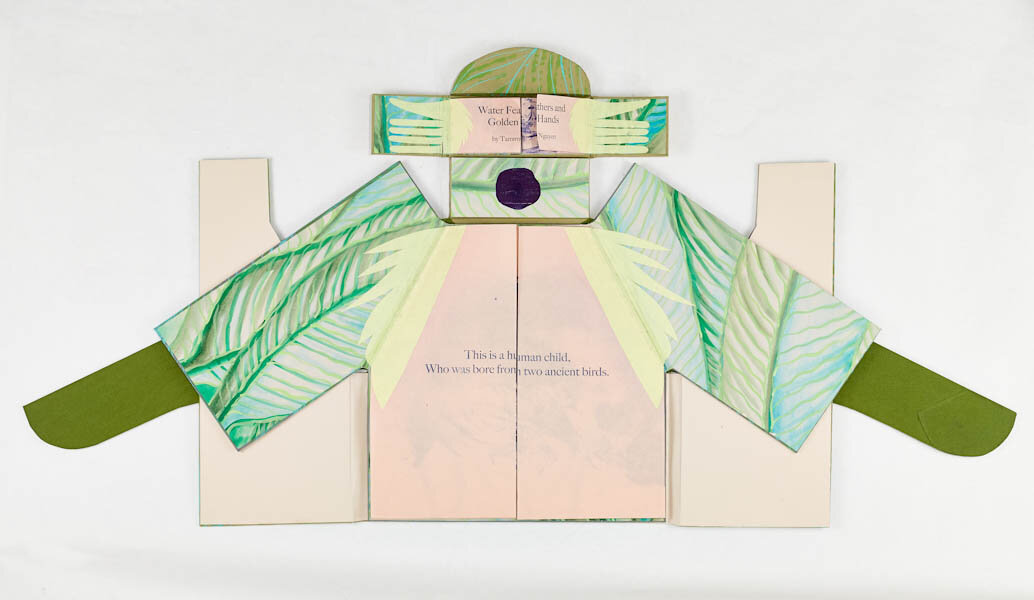

Water Feathers, Golden Hands

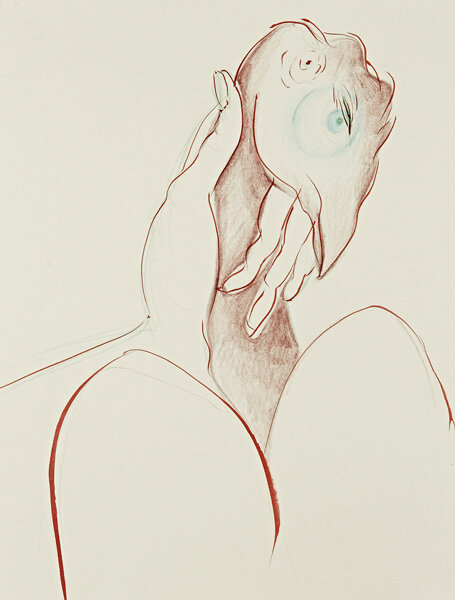

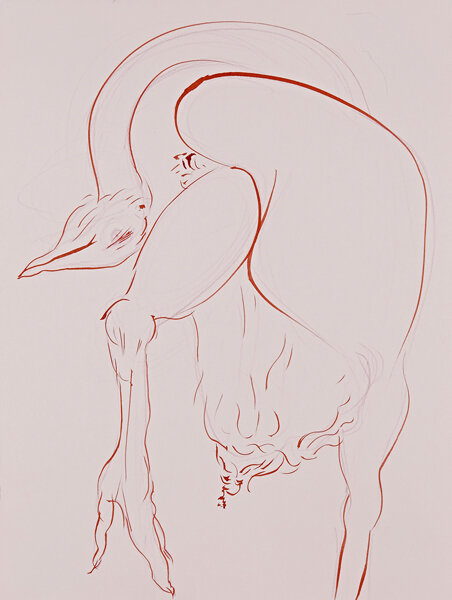

This is a human child,

Who was bore from two ancient birds.

Her father was a tiny owl,

Unique from his flock.

And with song that was more like a howl,

Her mother was an enormous hawk.

Mother hawk had the most beautiful feathers in the world.

Made of waves of water, she graced the sky as they swirled.

You could make out shimmering minerals,

As she flapped her wings in steady intervals.

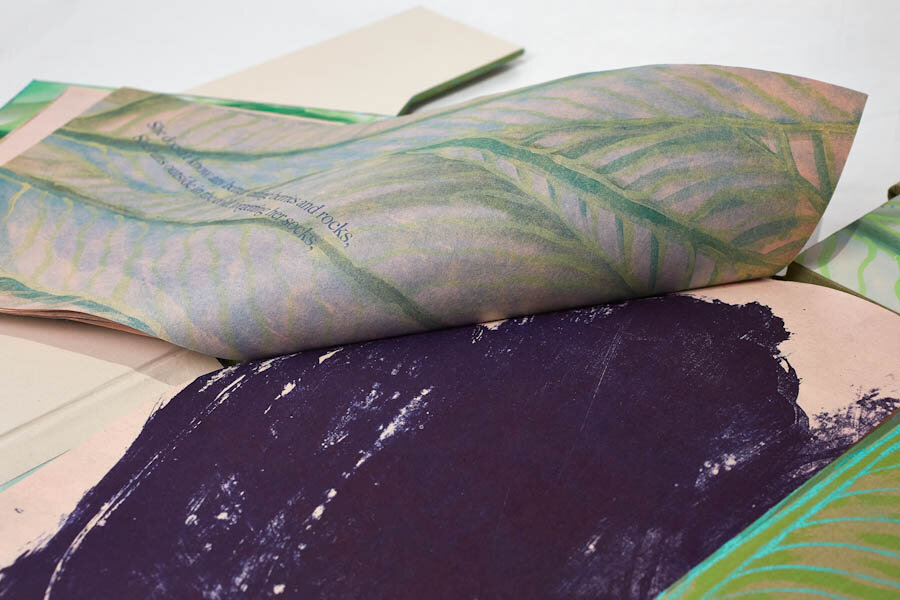

detail

Father owl was famous for his golden hands,

Skilled in picking and clawing, he was a crafty hunter,

He could target a prey, snatch it on command,

No need to worry, he’ll feed you whatever he musters.

When they saw that their egg hatched into a human,

Mother hawk and father owl were quite surprised,

Loving their daughter, but not knowing how to care,

They thought of ways, they sat, they agonized.

This child has a breathtaking gaze,

And a mouth outlined with full lips,

It was clear that if the bird couple didn’t give her tips,

She could be lost in the rain for days.

Mother hawk thought,

That if she could give her daughter her feathers,

Then her daughter could pursue whatever she sought,

By having mother’s water, she’d seize her endeavors.

Father owl thought,

That if he could give his daughter his hands,

Then his daughter could pursue whatever she sought,

She would be the one making all the demands.

detail

Mother hawk made her daughter a jacket out of banana leaves,

And she wove the water from her feathers into every stem,

She told her daughter, “Just put your mouth to your sleeve

And you will have the strength. Don’t be afraid of them.”

Father owl made his daughter a pair of glasses,

Molded from his hands, he used the best bark from a tree.

He told his daughter, “There are things I do not want you to see,

But when that happens, challenge them fiercely.”

What the bird couple did not realize,

Is despite the tools that they gave their child,

What they gave her internally was worse than the wild,

Her genetics would be the cause of her demise.

Her mother gave her a bad case of cholesterol,

And a temper that makes her spit boil, shooting fireballs.

Her mother gave her high blood pressure,

And a cold case of selfish, an endless hunt for treasure.

Her father gave her bad eyesight,

And some anxiety that keeps her from sleep at night.

Her father gave her bad digestion,

And a tendency for paranoia, she tends to feel threatened.

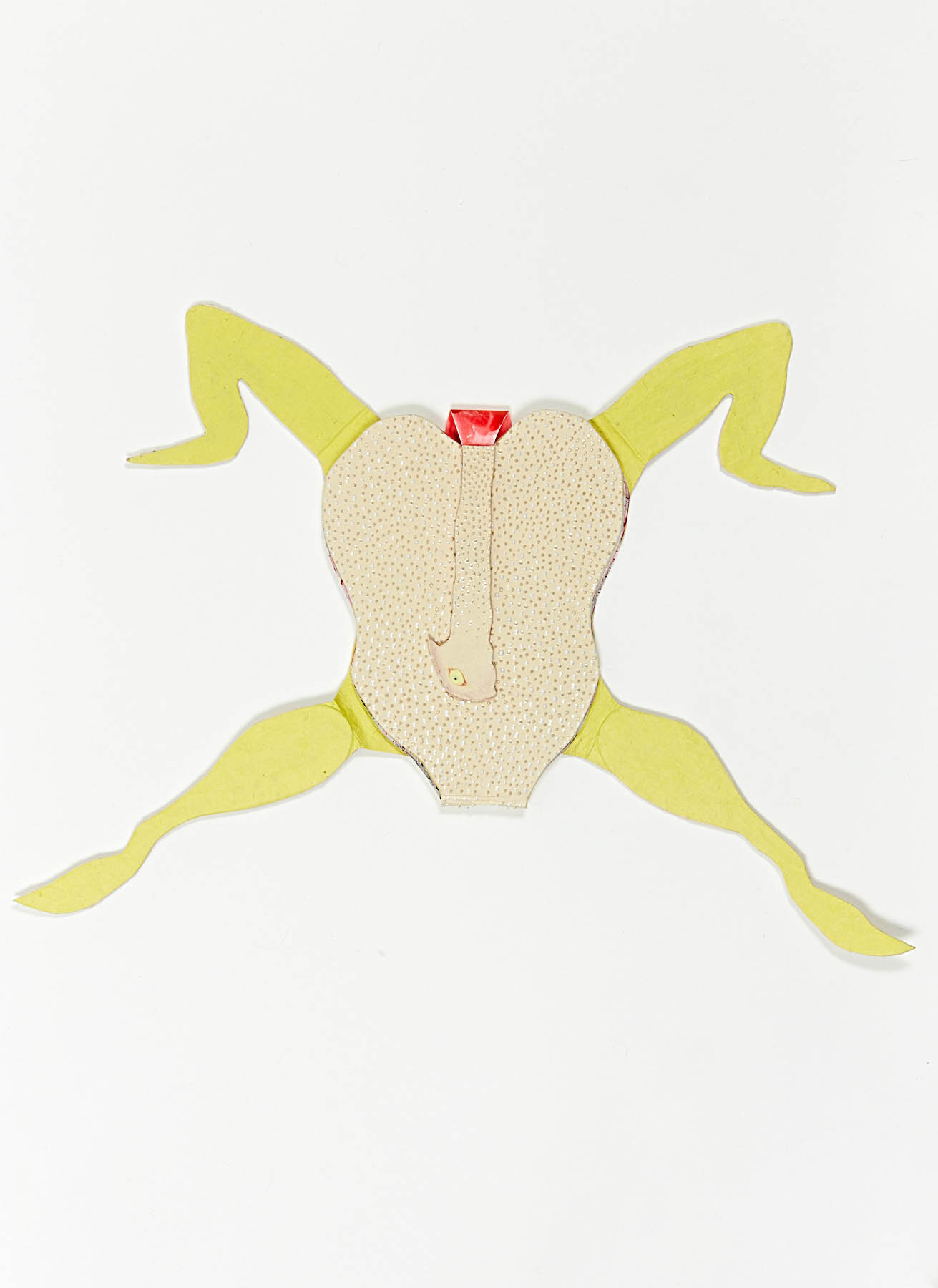

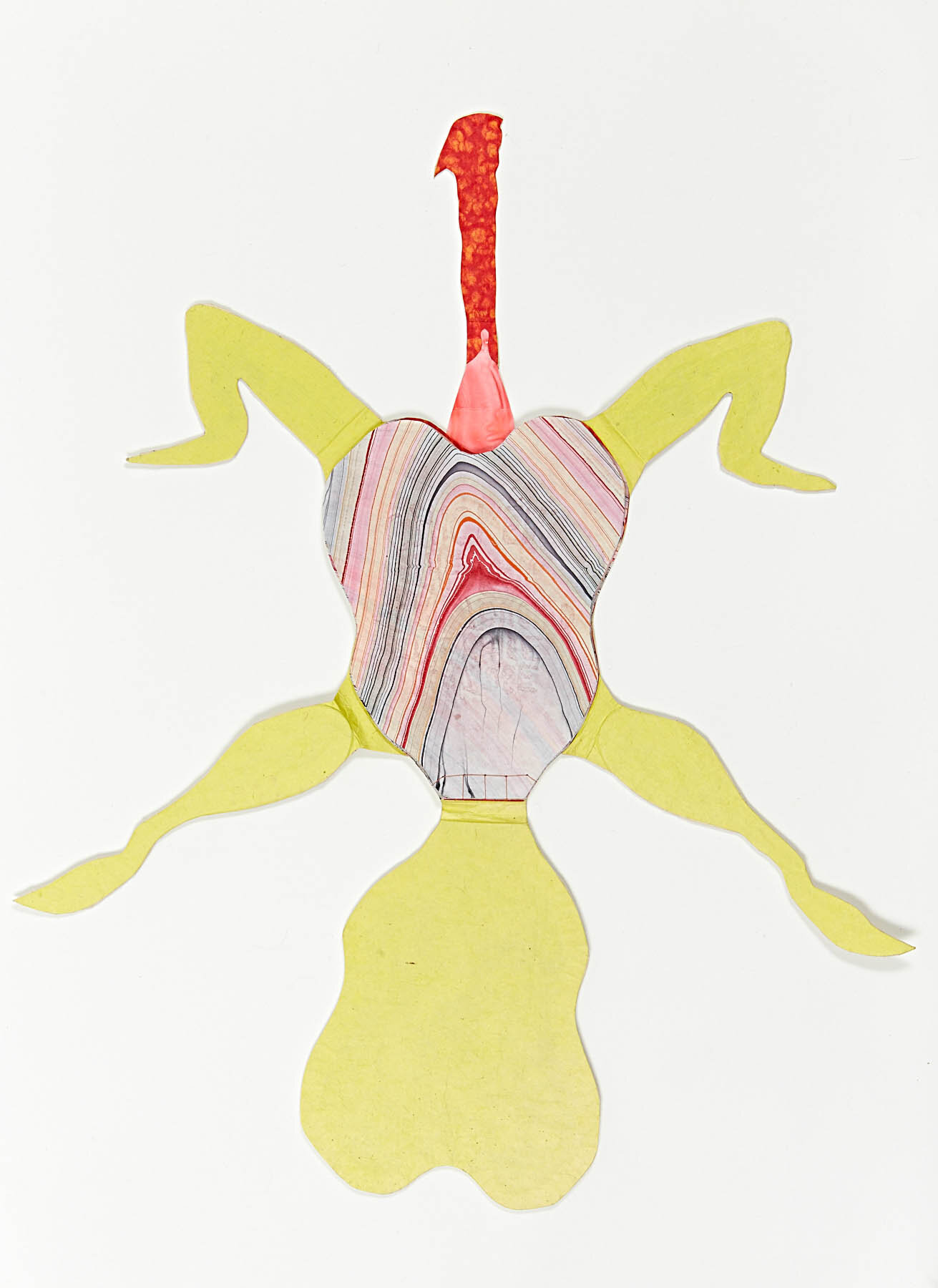

You are holding this child; organs you’re viewing,

In fact, she is aging, page turn to page turn.

But she only wants to be where the few sing,

Making discoveries impossible to churn.

She’s wide-eyed and unafraid of the universe,

Protected by her parents’ love and armor,

How guilty they might feel to see their efforts reverse,

We all know that one day she can’t go on for longer.

detail

She doesn’t know any better, eating berries and rocks,

She runs outside in the cold, forgetting her socks,

She doesn’t know that the stuff inside will take over,

Look at her now; tell her something before she gets older.

So what would you tell this child,

Now that you’ve seen her intestines,

Try and save her?

Don’t let her go where she is destined.

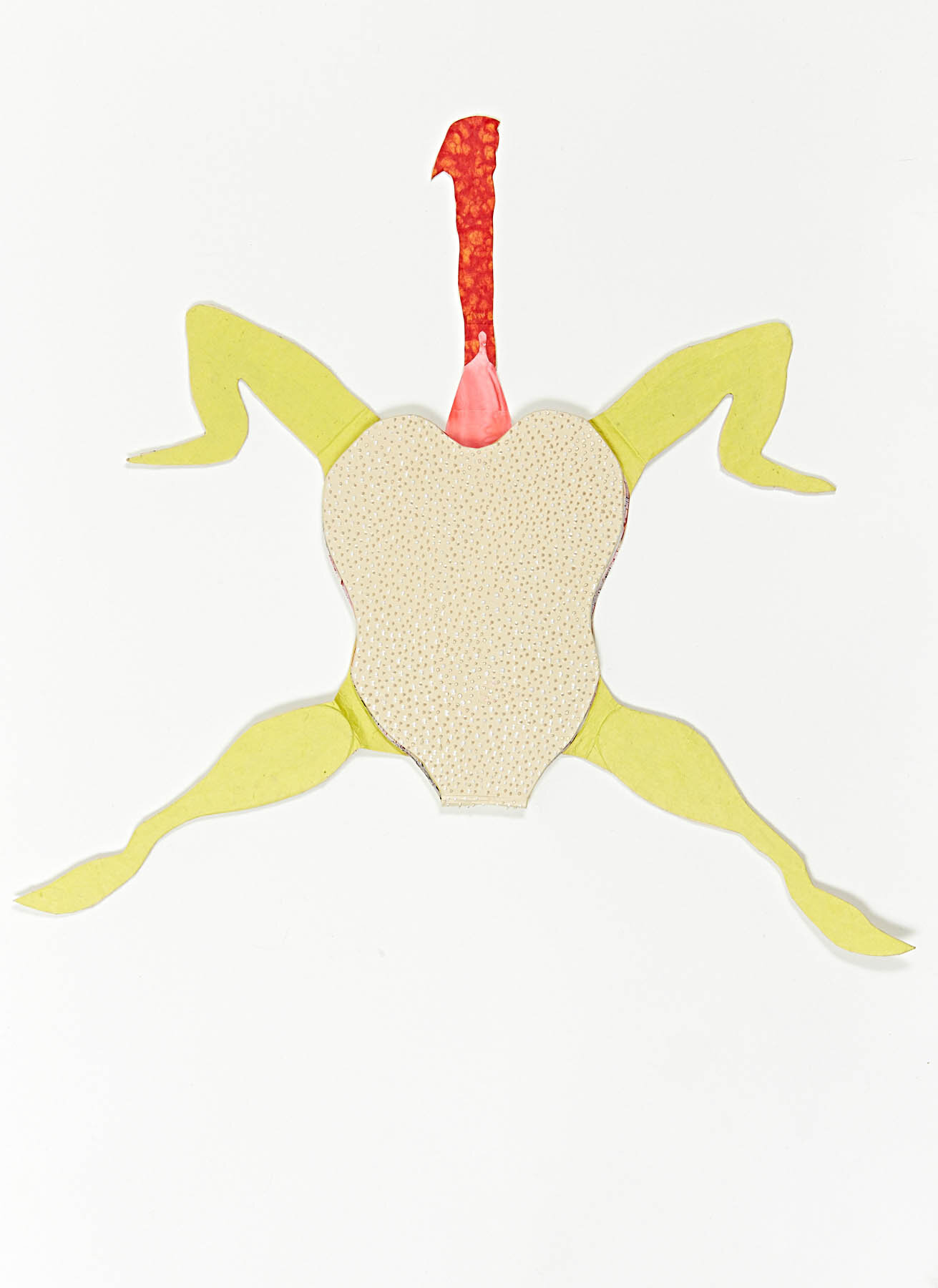

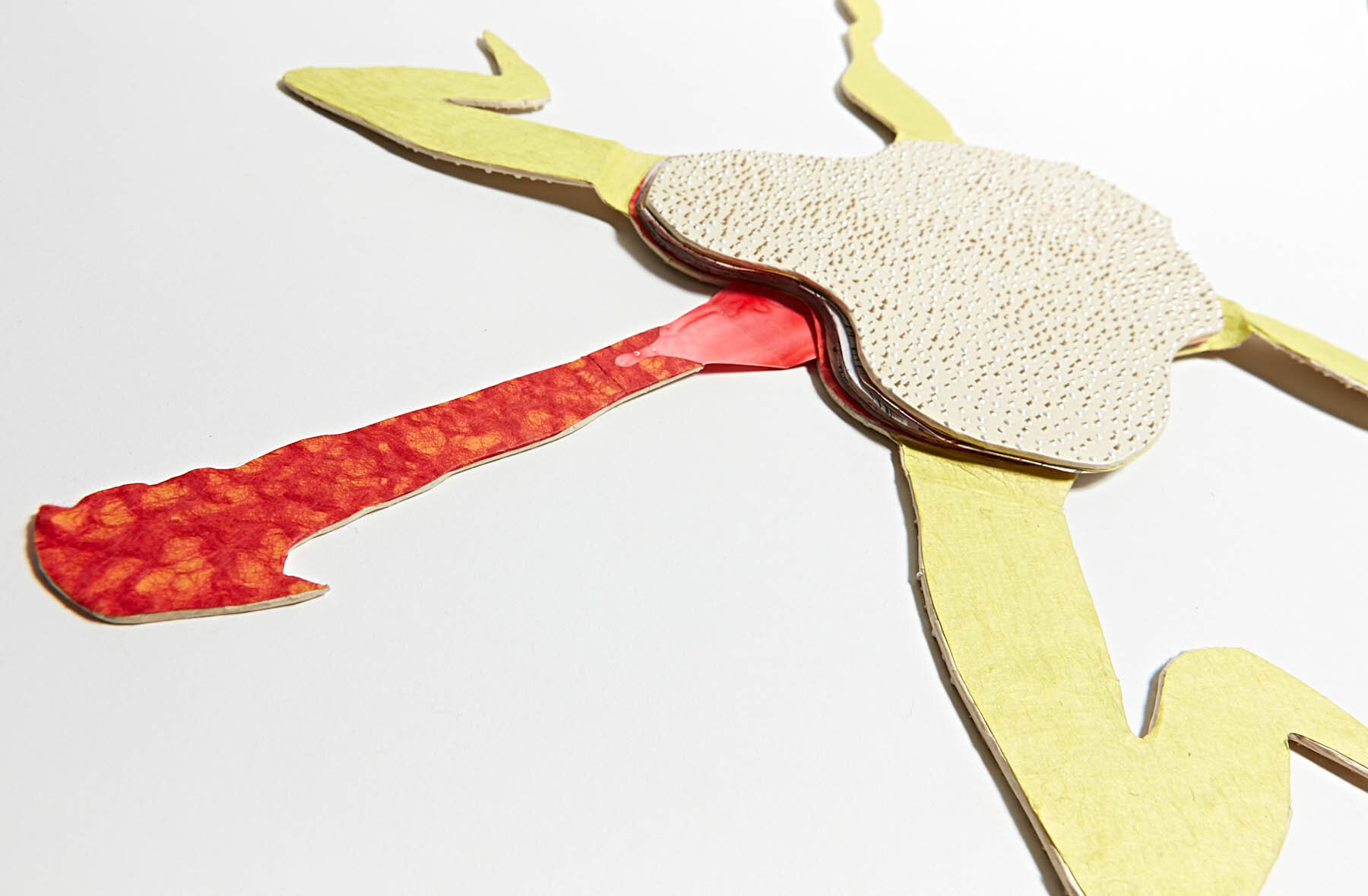

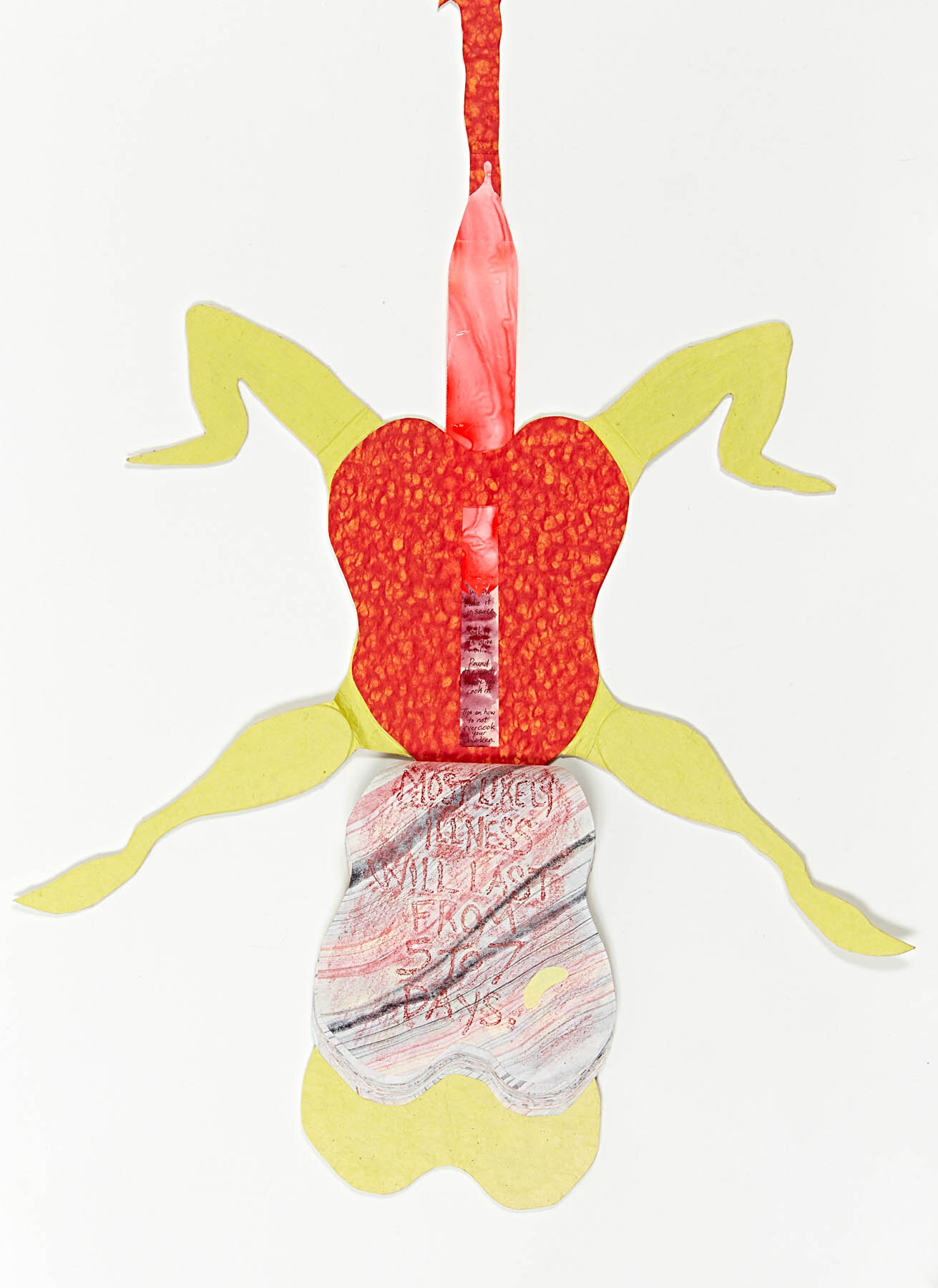

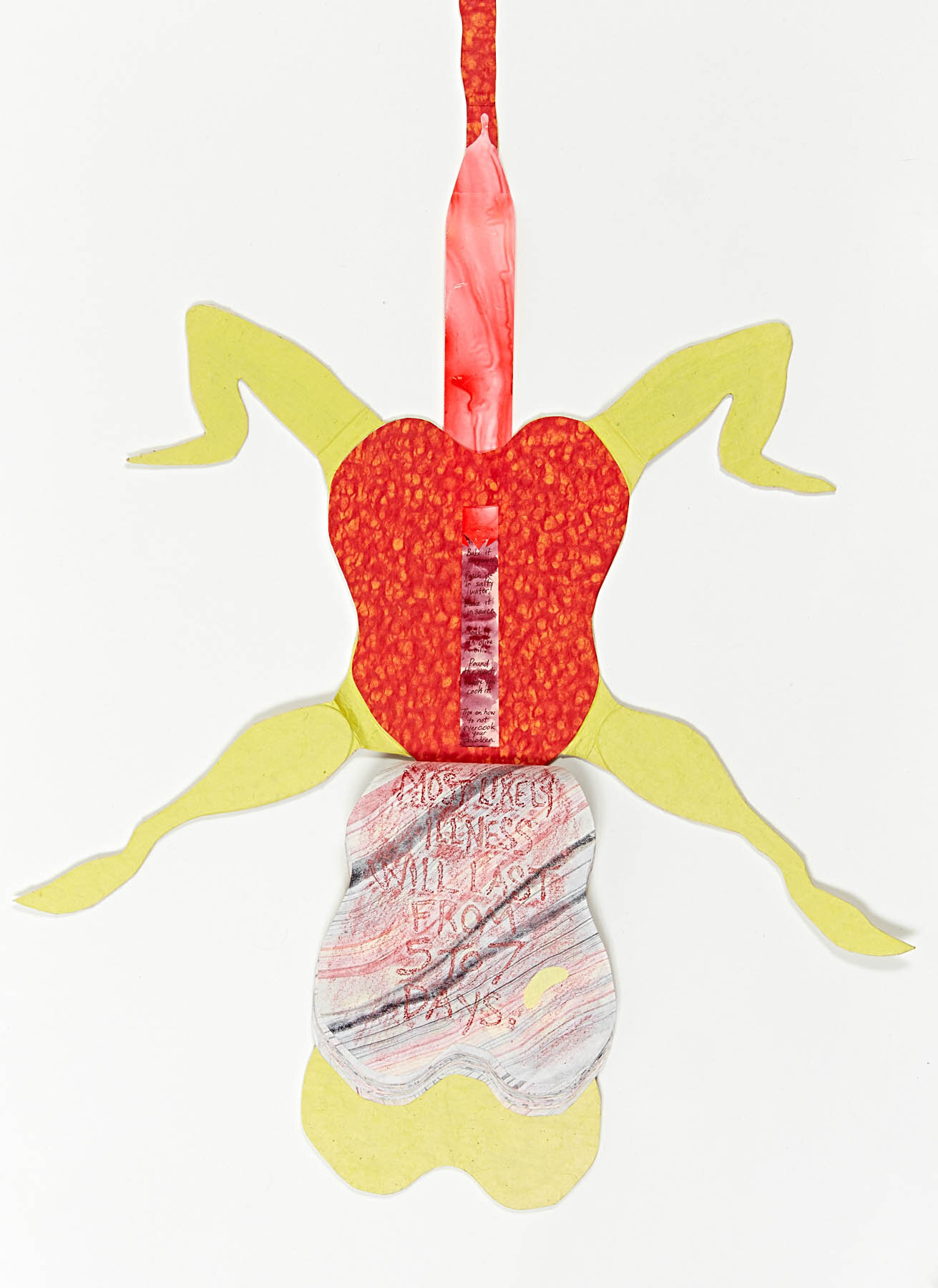

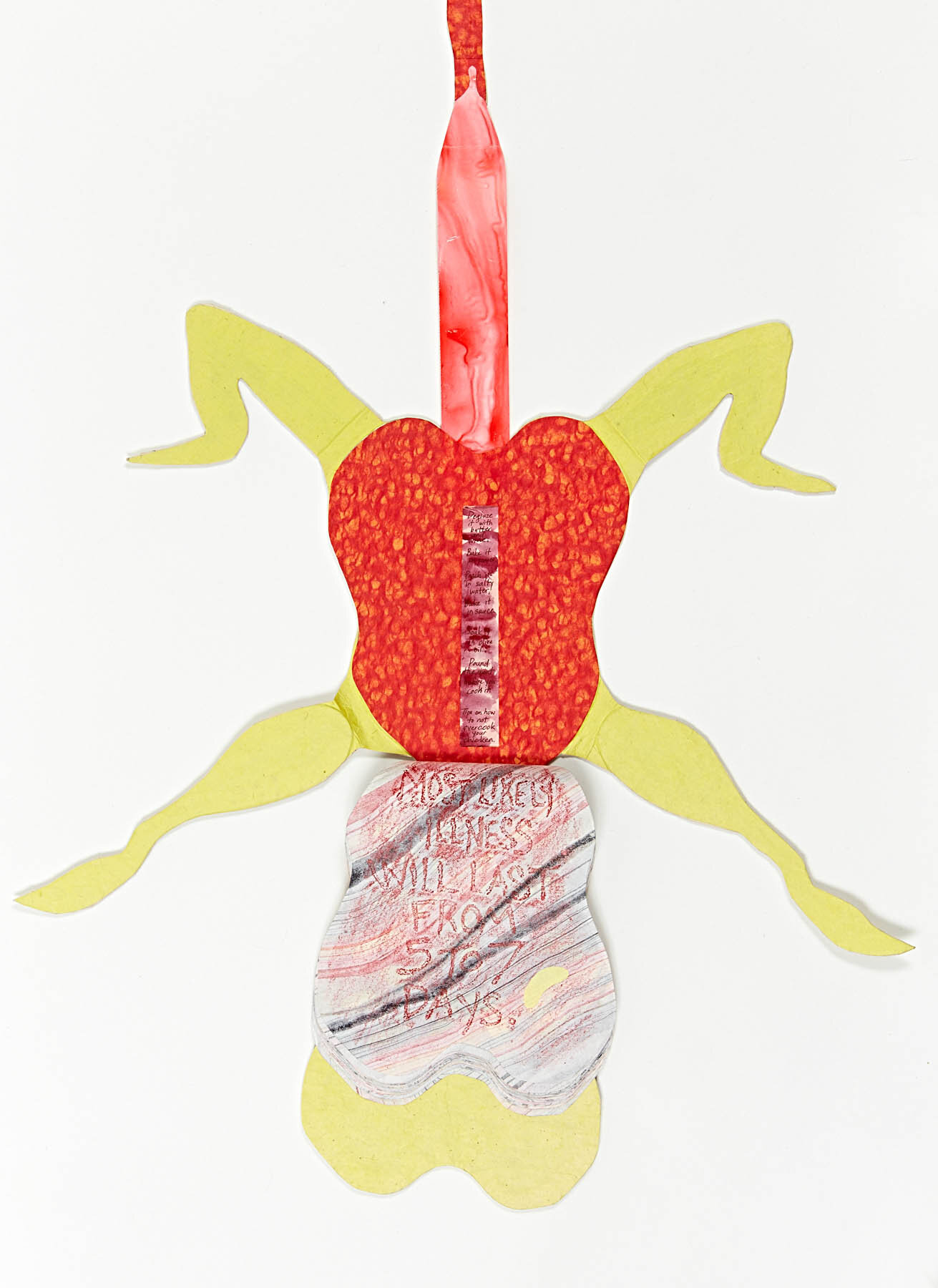

Pellet

Avian Flu

The Scream

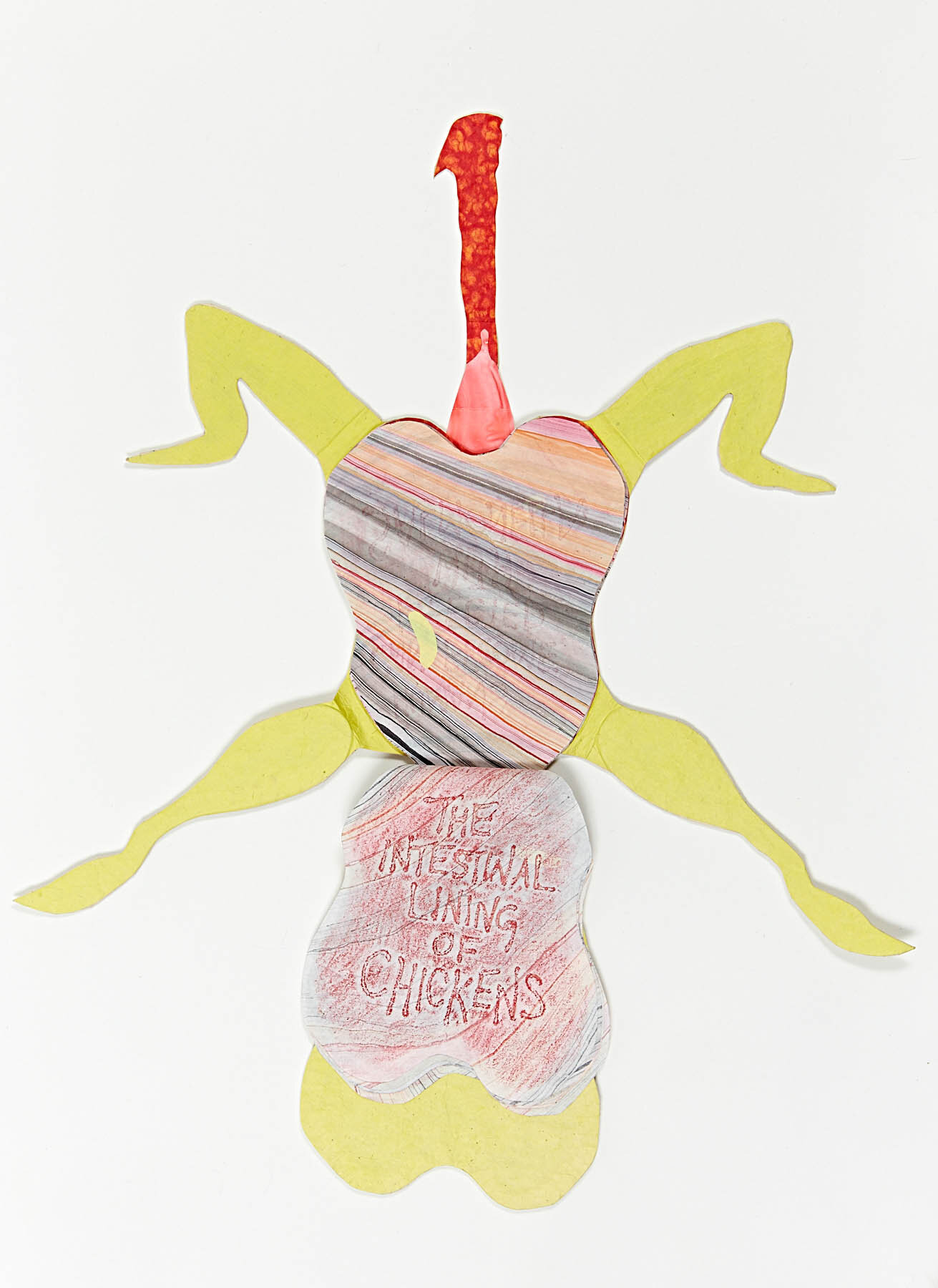

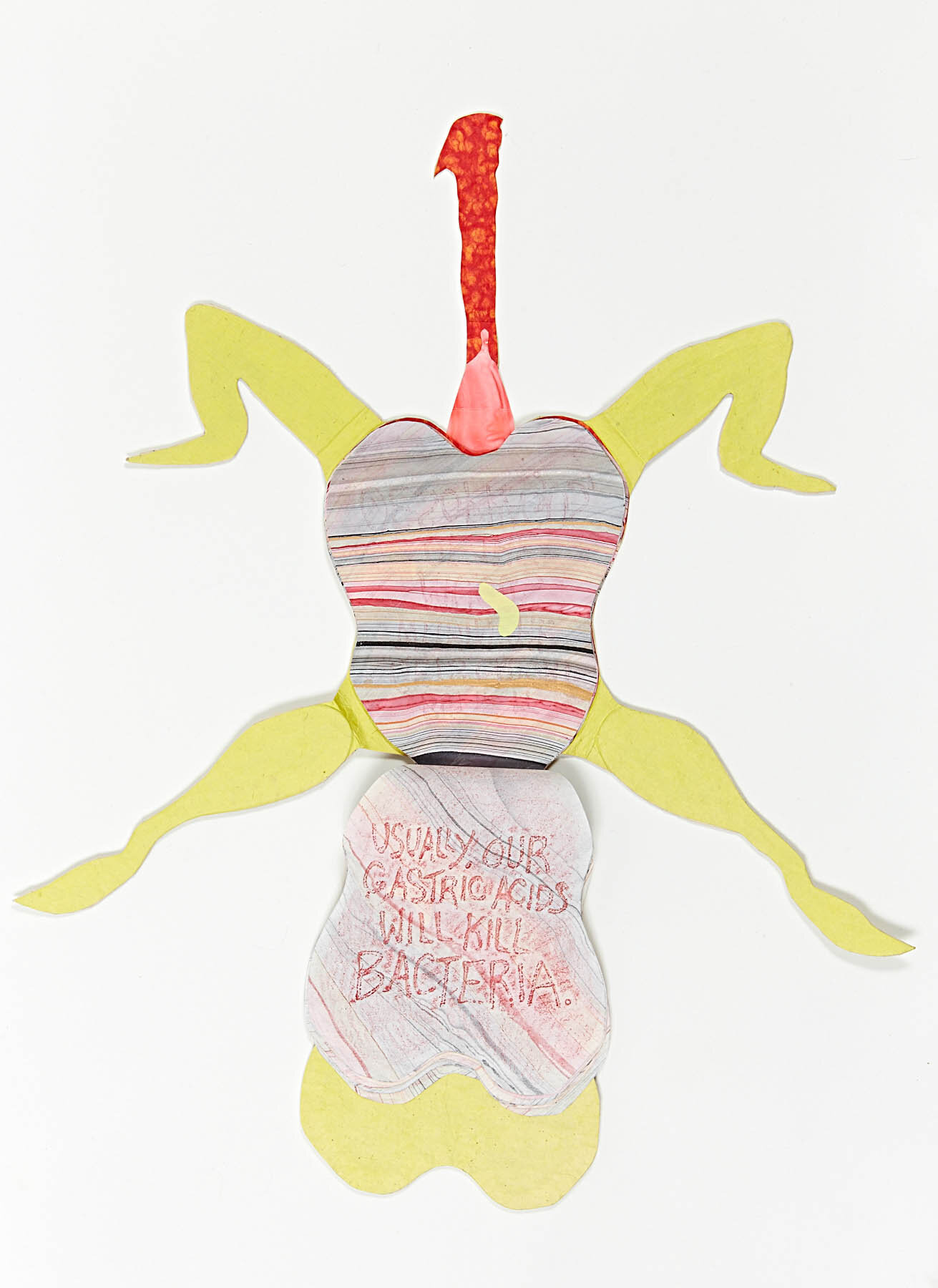

Salmonella

Don't use the knife that touched the raw chicken.

You could catch Salmonella

a type of food poisoning commonly linked to poultry.

It is a rod-shaped bacteria that thrives in

detail

detail

the intestinal lining of chickens.

Humans can become infected with Salmonella

through ingesting undercooked chicken.

Usually our gastric acids will kill bacteria.

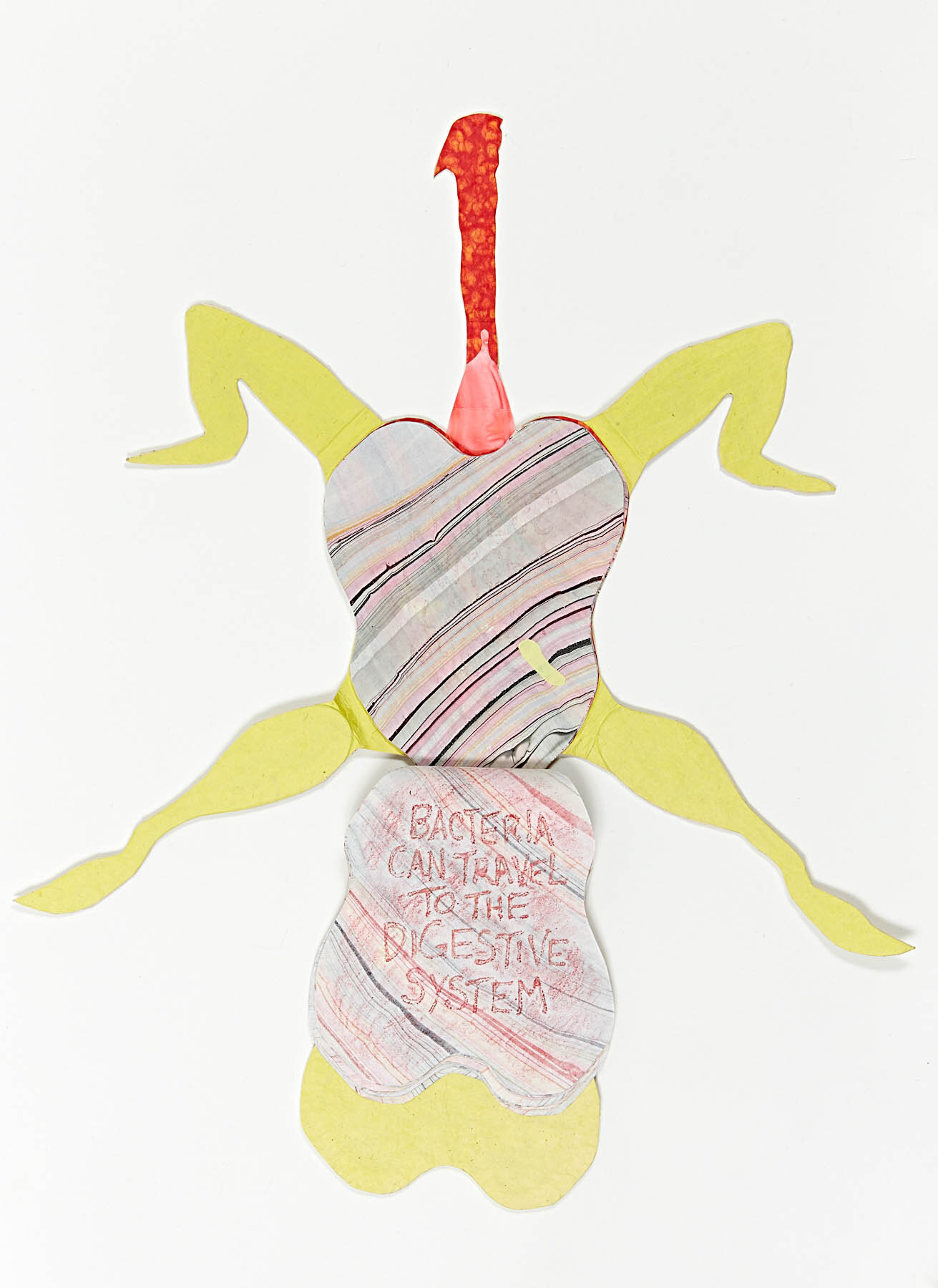

But if it gets caught within the mucus of the oesophagus,

bacteria can travel to the digestive system,

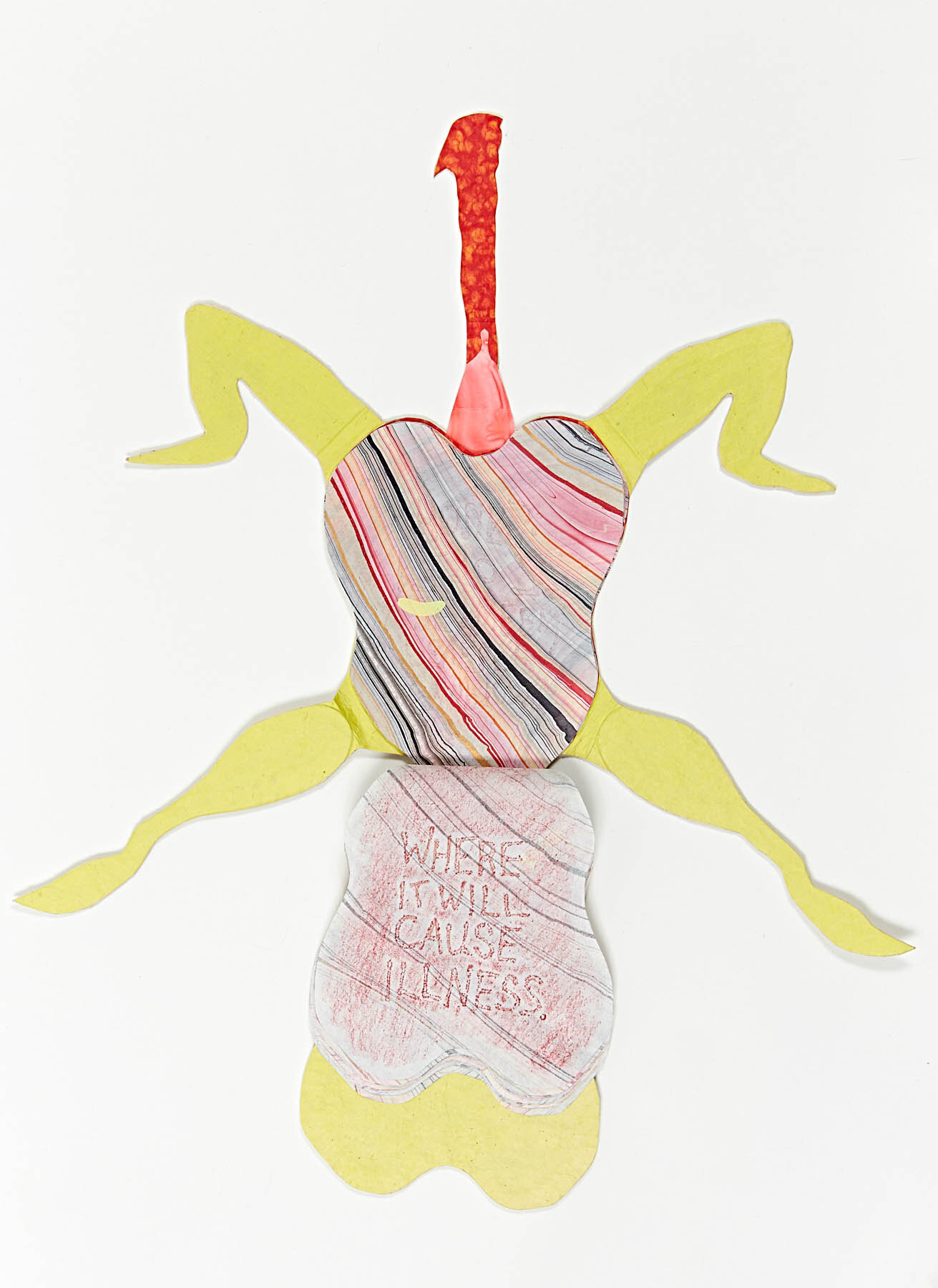

where it will cause illness.

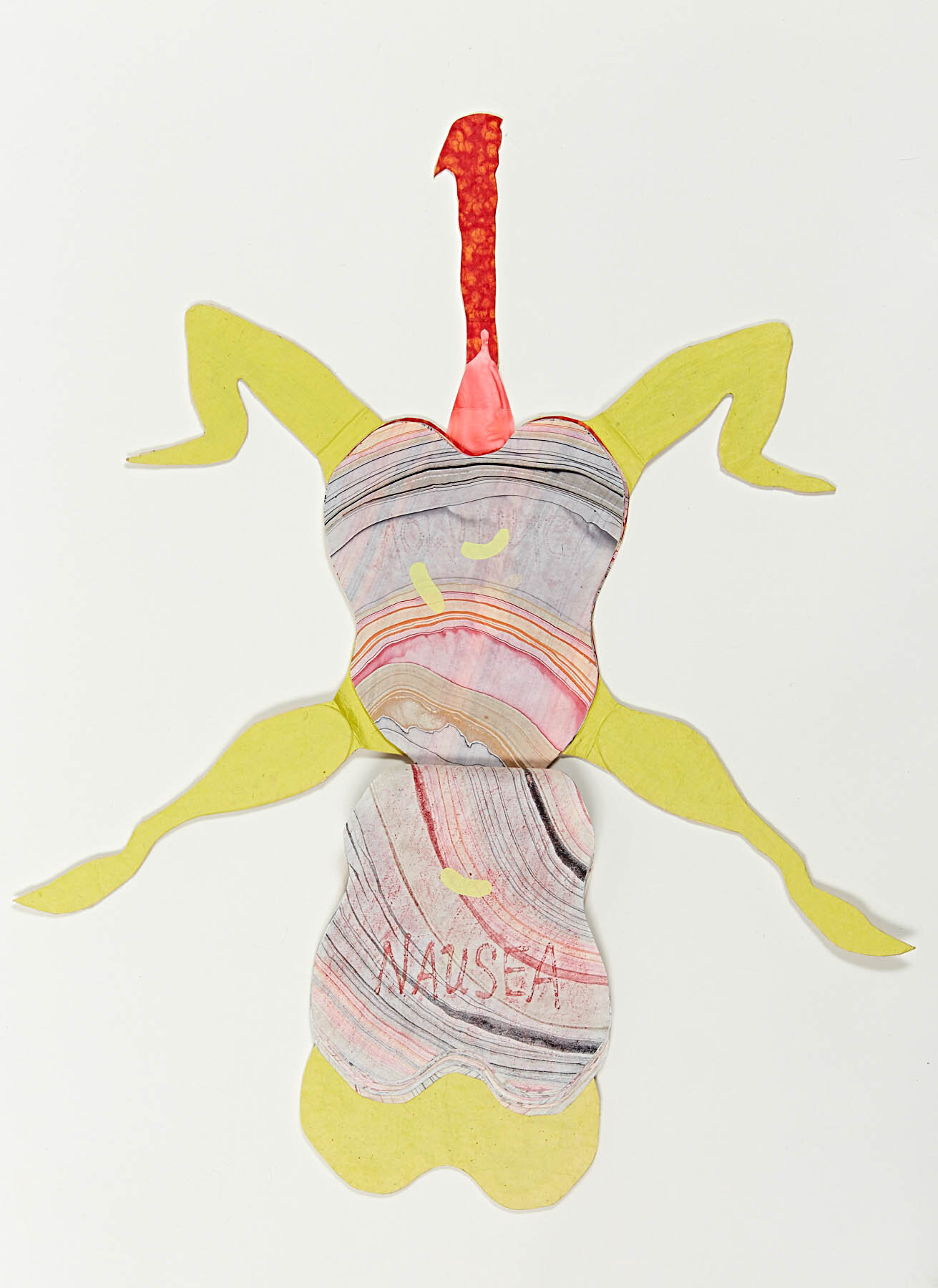

Symptoms develop between 12 to 72 hours.

NAUSEA

STOMACH CRAMPS

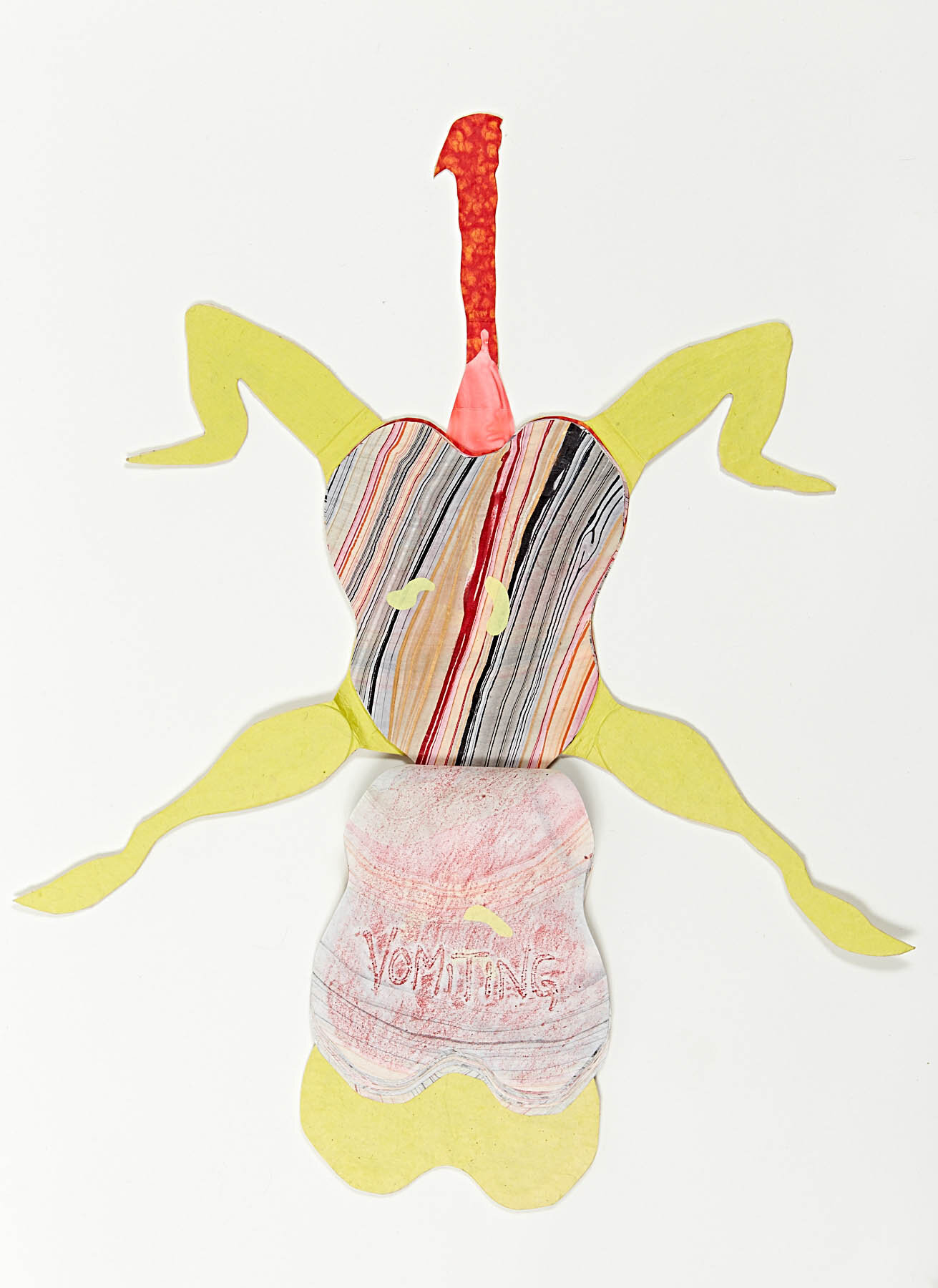

VOMITTING

CHILLS

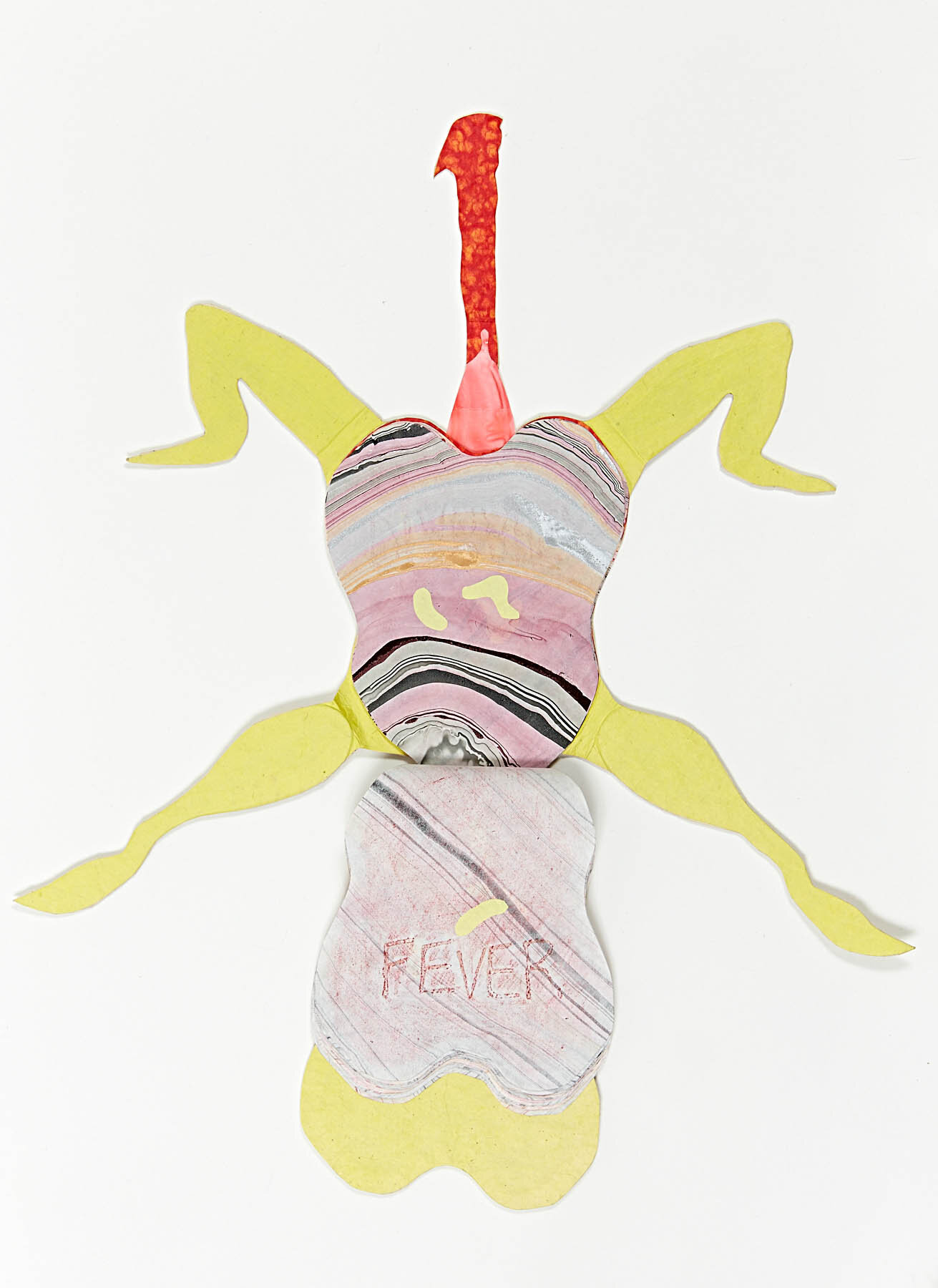

FEVER

DIARRHEA

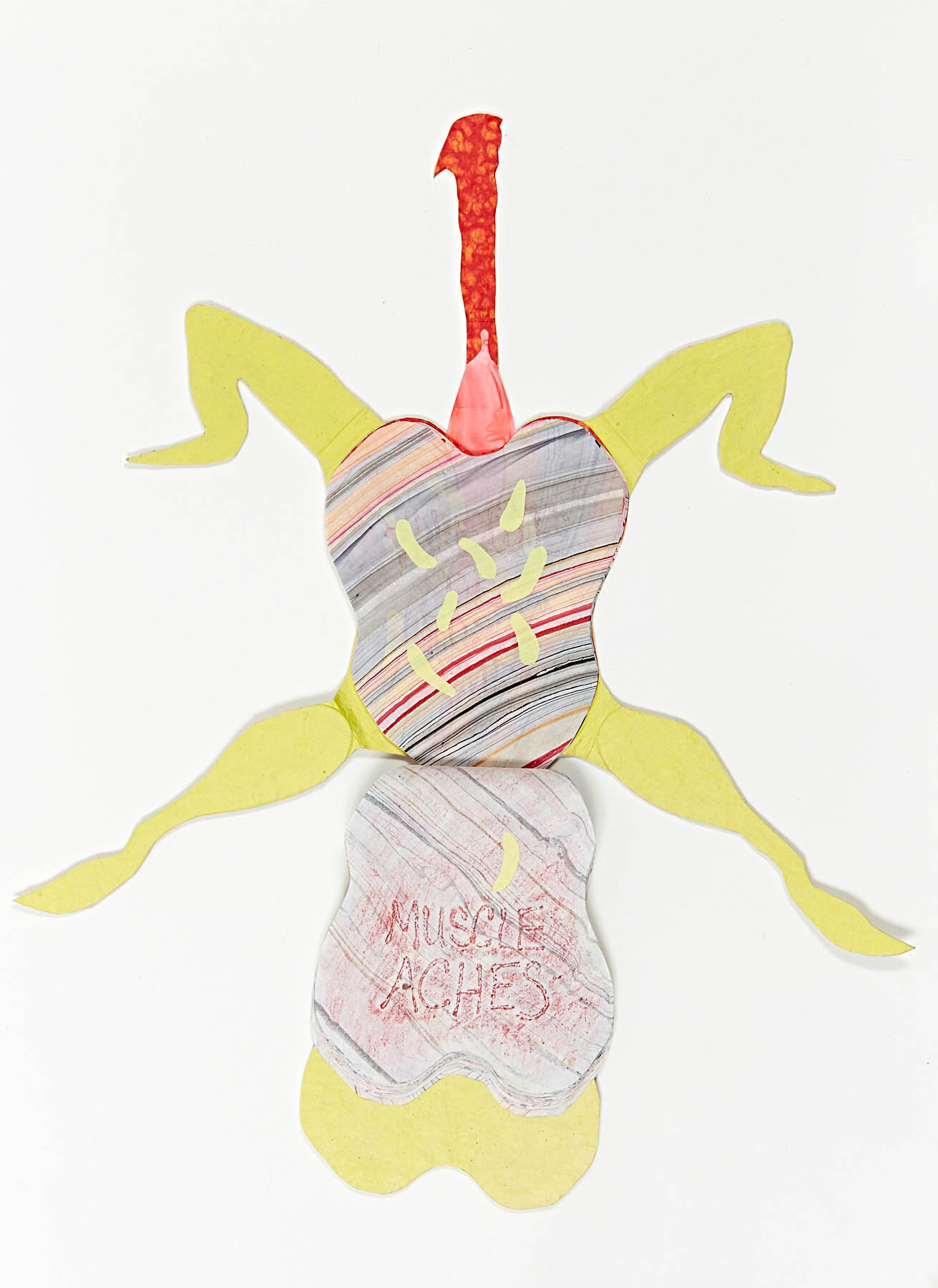

MUSCLE ACHES

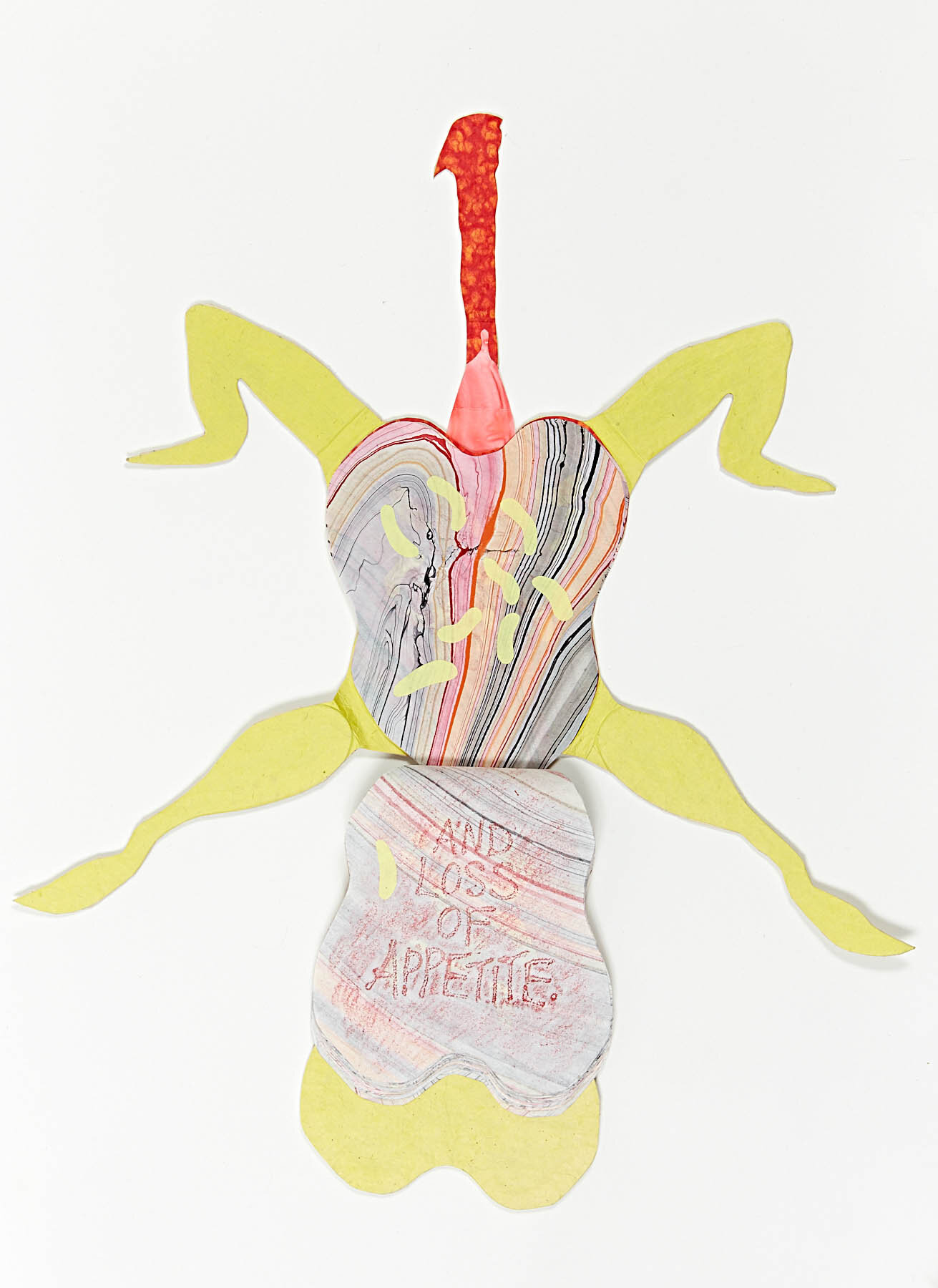

AND LOSS OF APPETITE

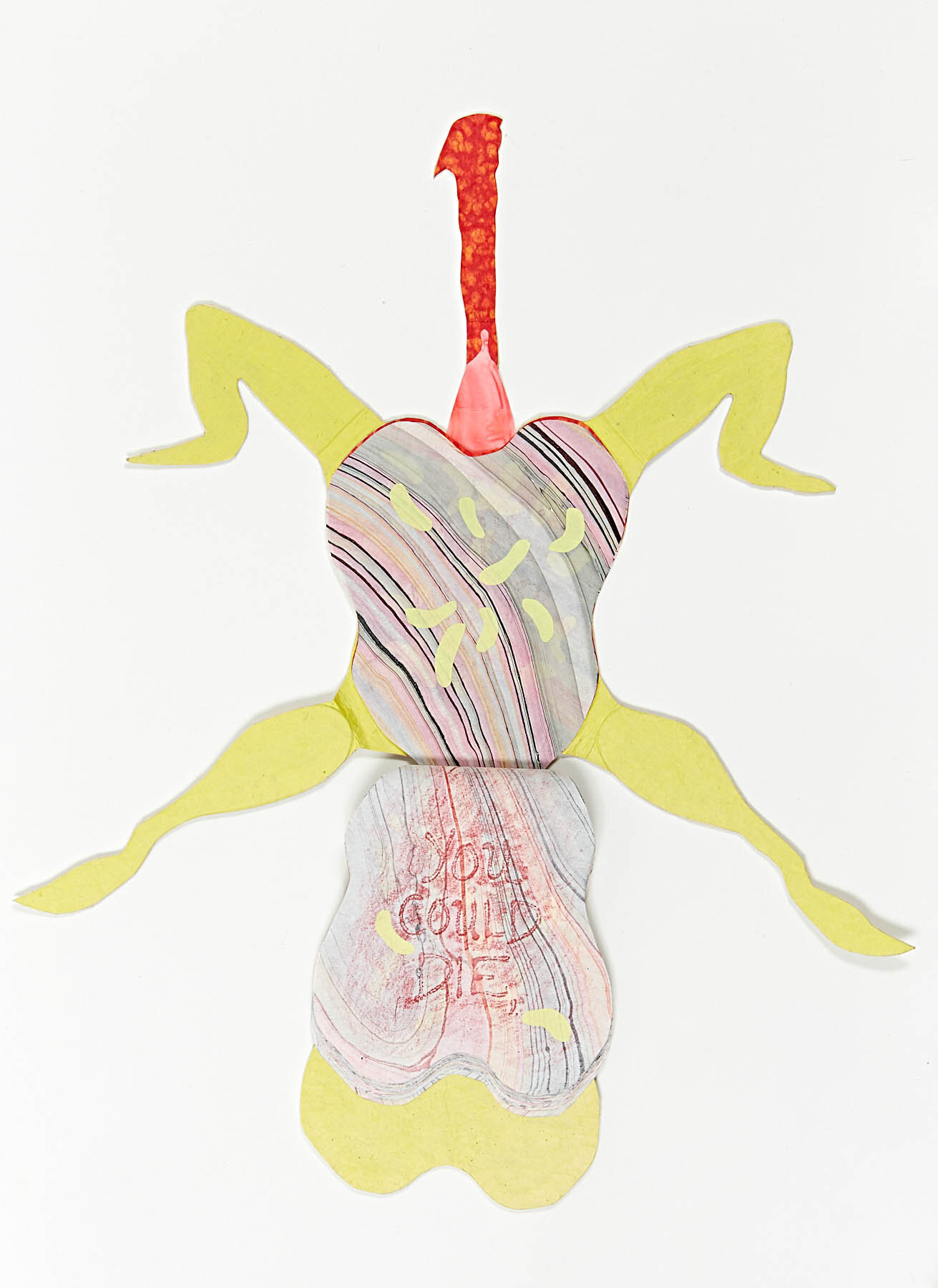

You could die,

detail

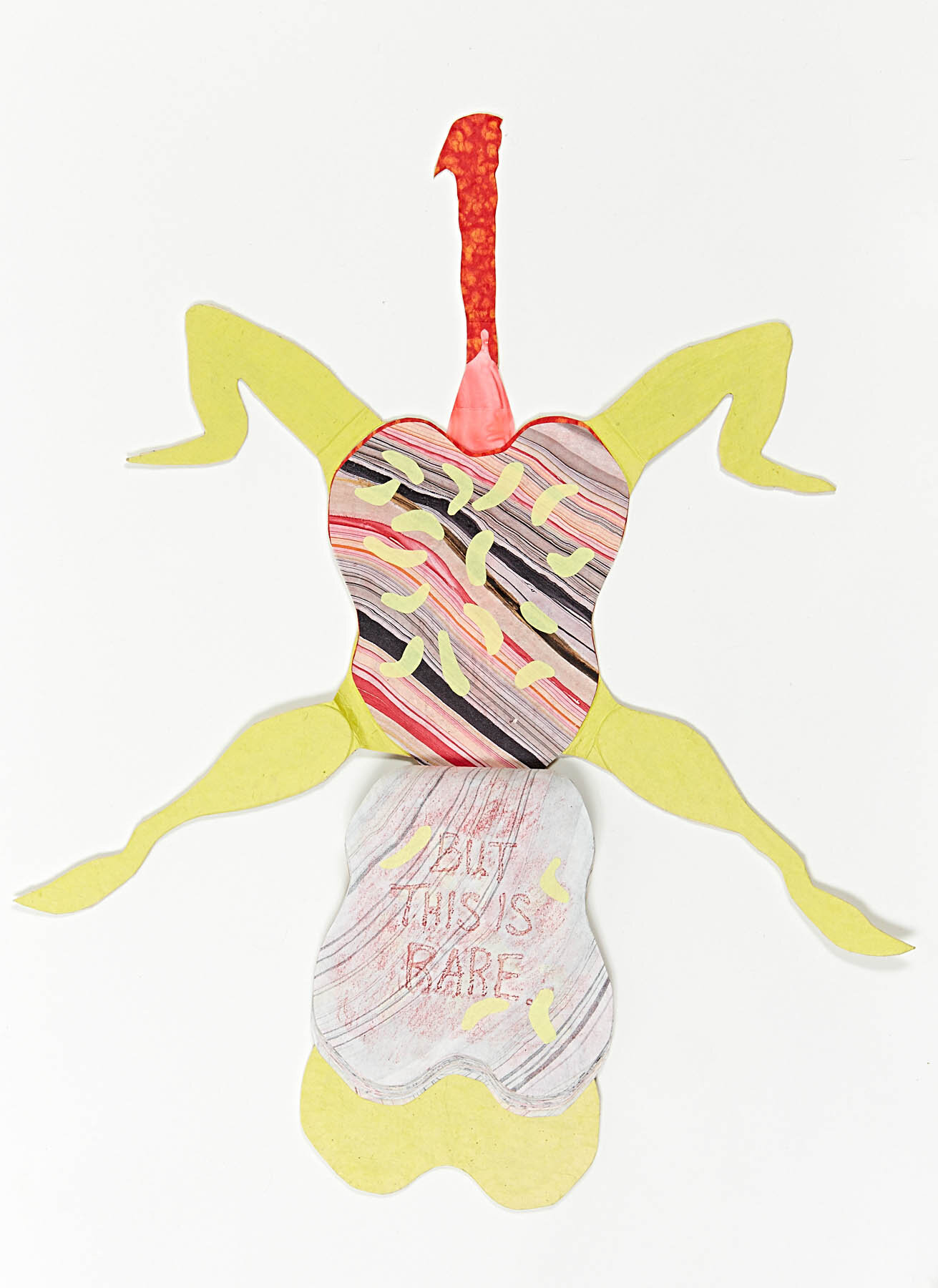

but this is rare.

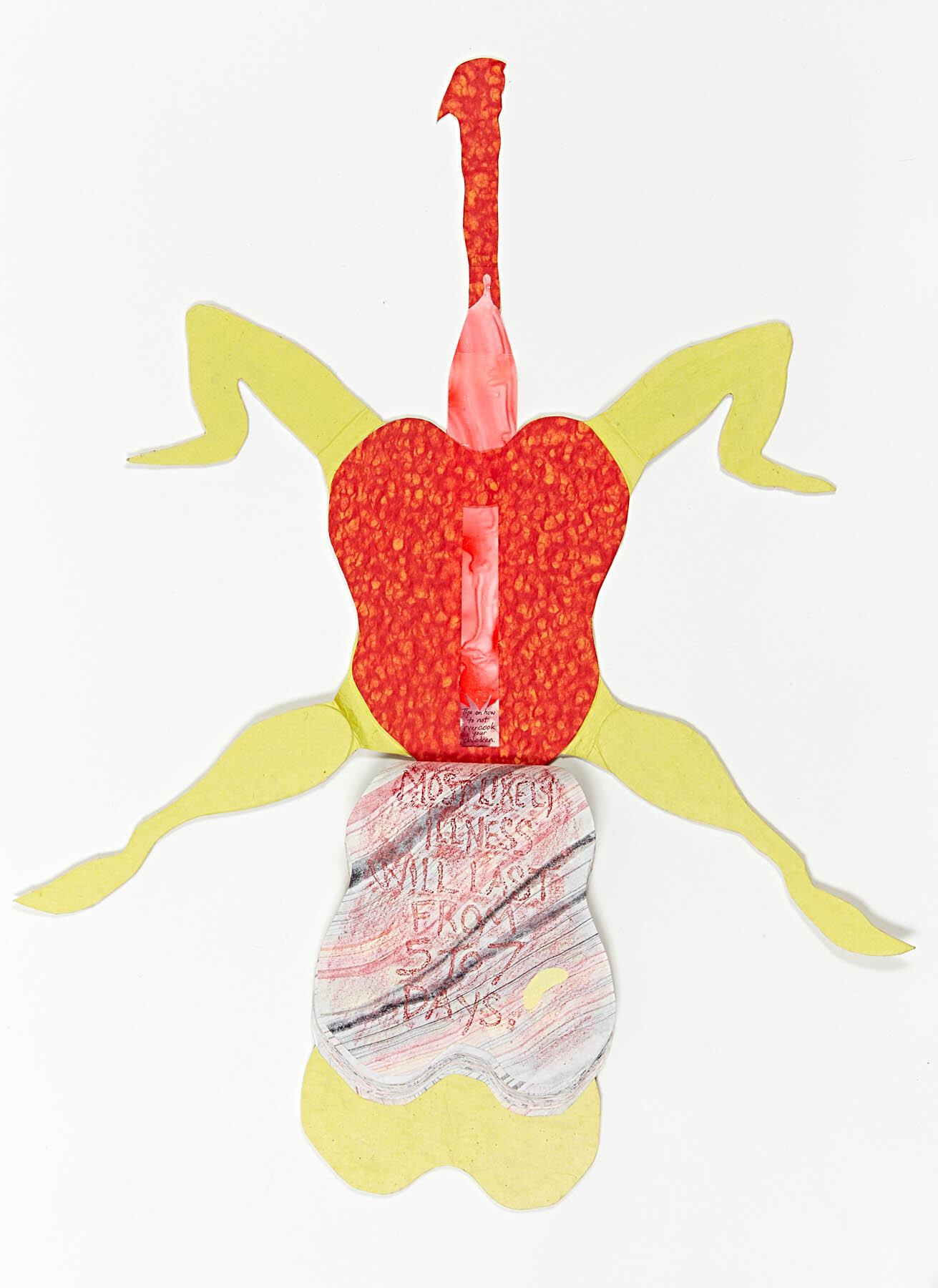

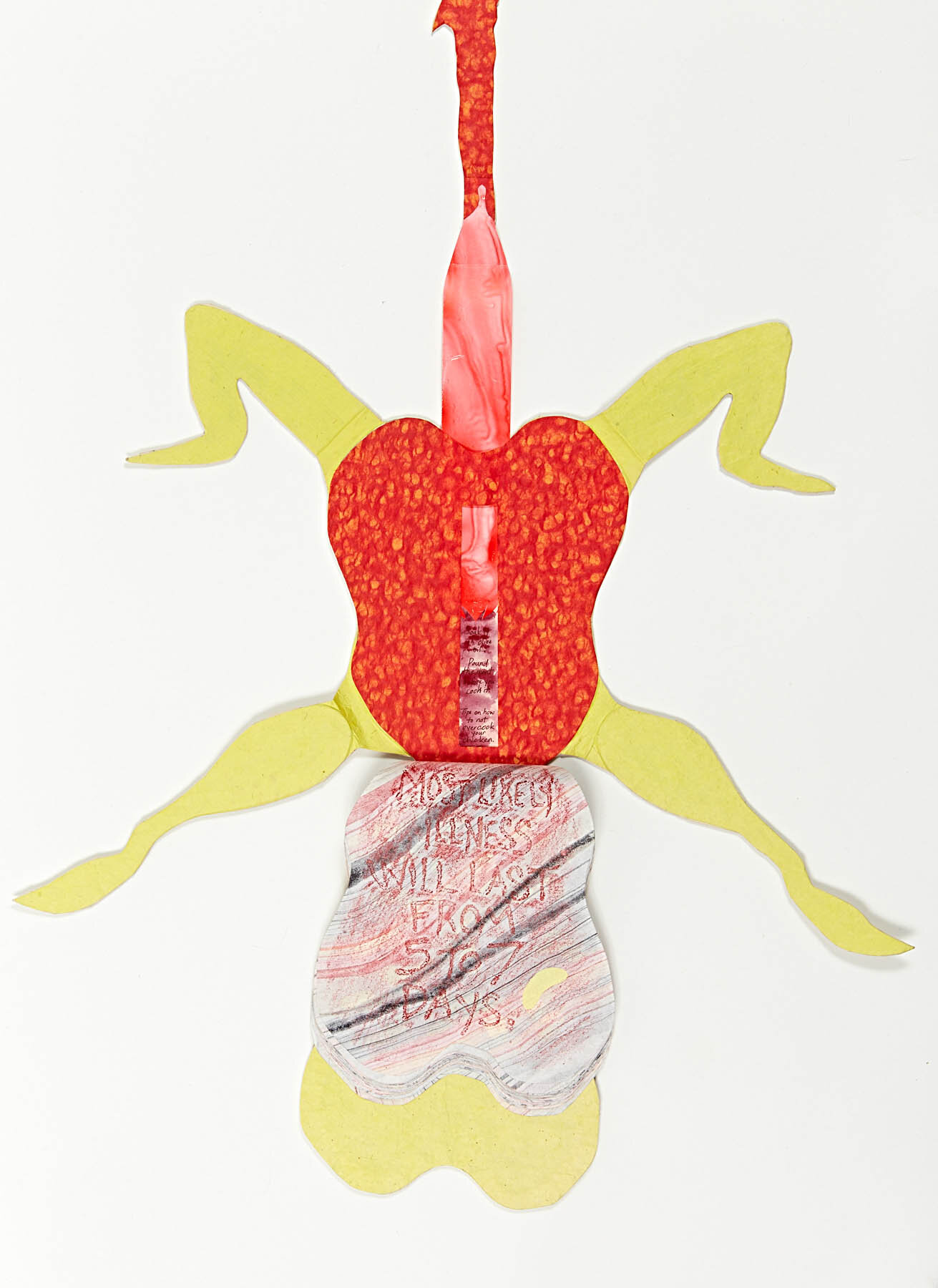

Most likely illness will last from 5 to 7 days.

Tips on how to not overcook your chicken.

Pound the meat before you cook it.

Soak it in olive oil.

Poach it in salty water.

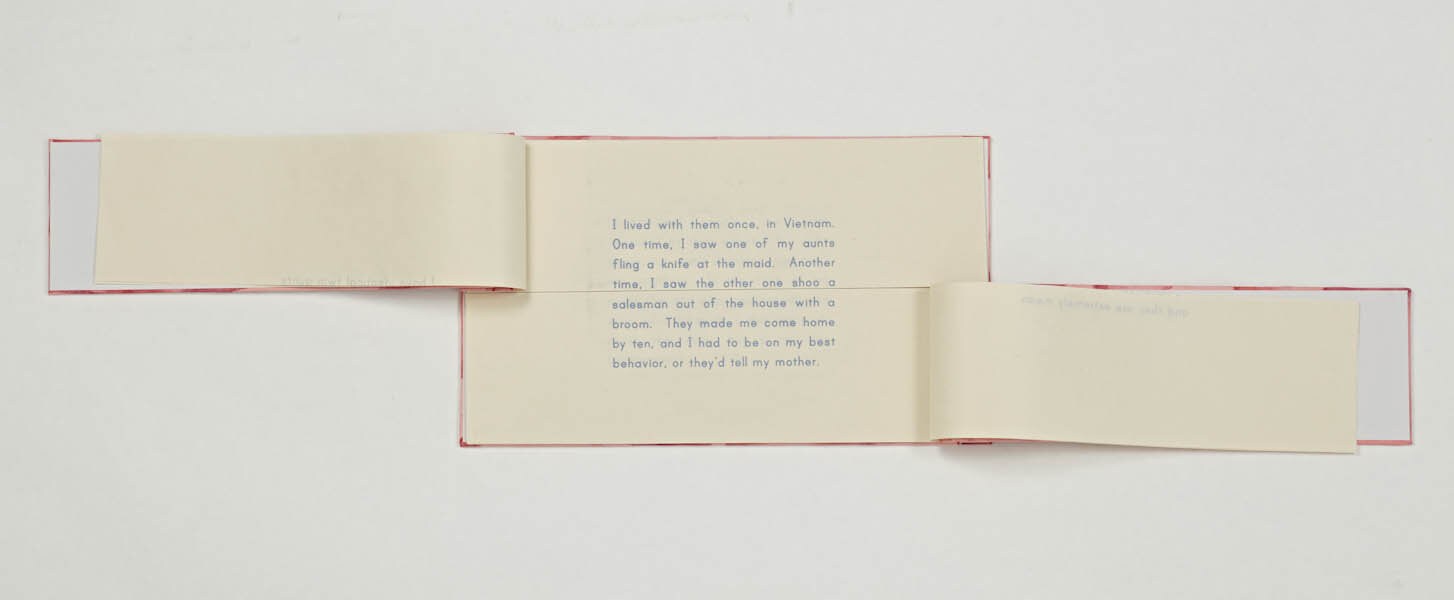

My Twin Aunts

I have identical twin aunts and they are extremely mean.

I lived with them once, in Vietnam. One time, I saw one of my aunts fling a knife at the maid. Another time, I saw the other one shoo a salesman out of the house with a broom. They made me come home by ten, and I had to be on my best behavior, or they’d tell my mother.

Vietnamese people are born censored by their elders. You can’t argue; you can’t disagree; you can’t say anything. In the case of my aunts, the one who was two minutes older was the boss. I was obviously never the boss, but I had my imagination.

My aunts were America-worshipers. They loved American things, from their cars to their lipstick. When they upset me, I would imagine them as conjoined hawks.

If they loved America so much, then being conjoined twins would be a perfect democracy. They would have to negotiate everything, otherwise they would have heart failure, bone failure, liver failure, brain failure, whatever failure, as they would have to share an organ to survive.

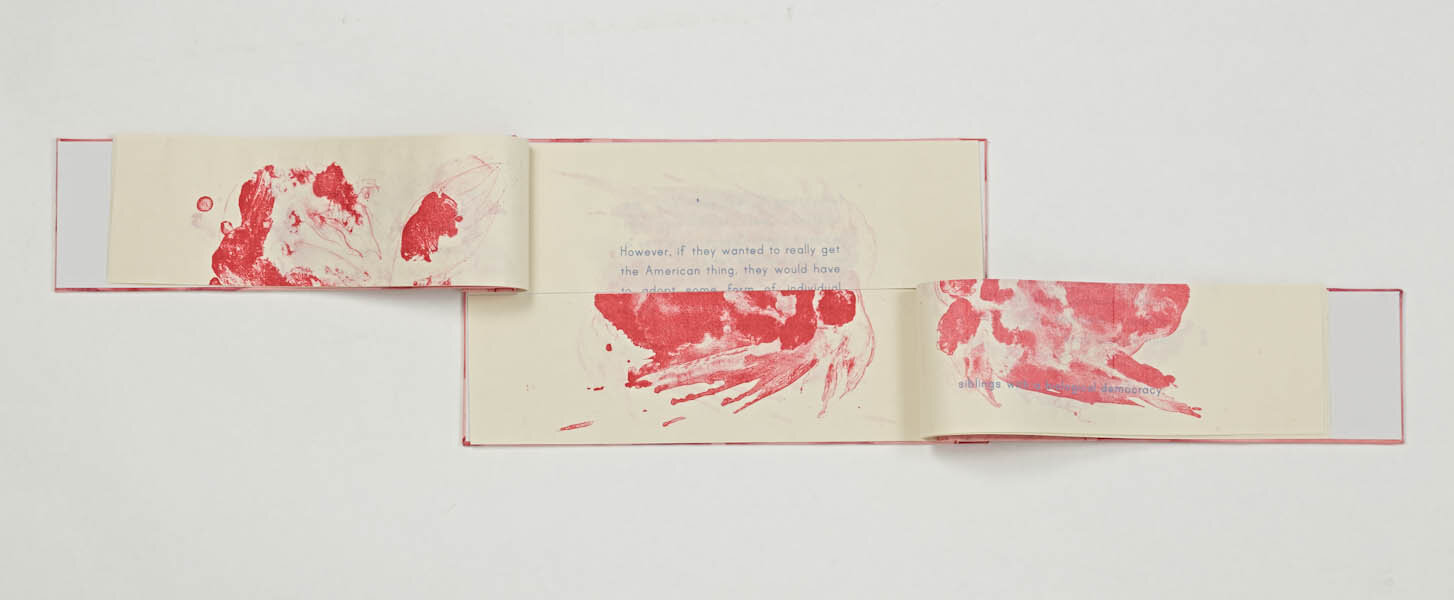

However, if they wanted to really get the American thing, they would have to adopt some form of individual pursuit, causing them to fly in different directions and breaking their physical bond.

Funny thing is that soon after the Americans went to Vietnam and released Agent Orange there was a surge in conjoined twins— siblings with a biological democracy.

Children are sometimes worshipped in Vietnam because of their innocence. Some Vietnamese people regard conjoined twins as extra holy. They don’t live long and often remain children.