The Gazing Pool for Who and Ai

“The Gazing Pool for Who and Ai” was a series of paintings included in “Necessary Fictions” curated by Zoe Butt and Bill Nguyen with Ha Ninh Pham at the Factory Contemporary Arts Centre in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam in 2019.

(The following essay was written for the occasion of “Necessary Fictions”.)

Ai Ai Ai Ai Ai Ai Ai

Who Who Who Who Who Who WhoBy Zoe Butt

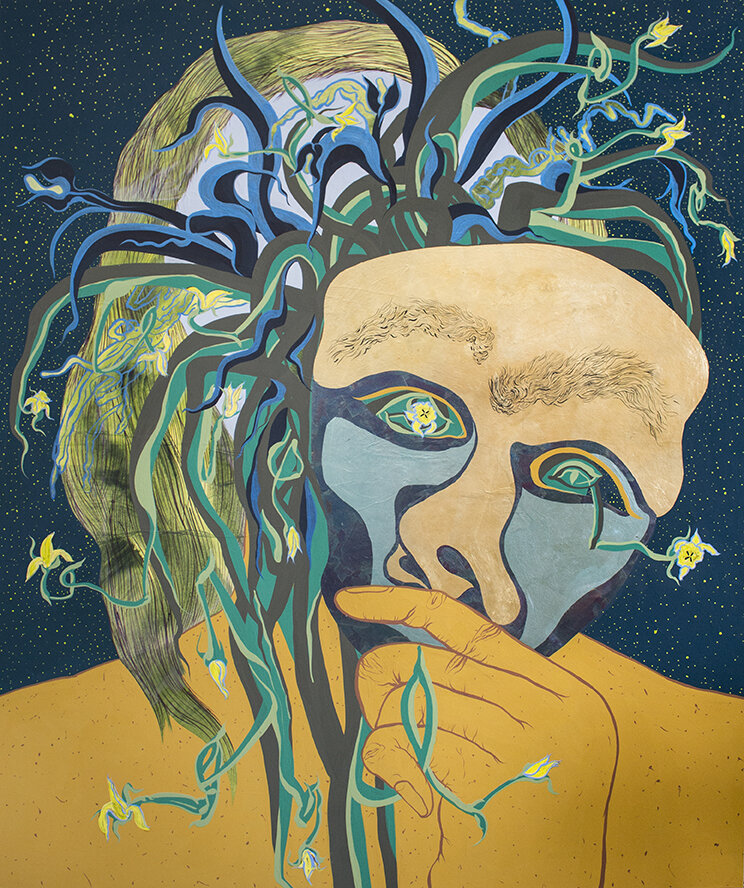

I See You, You, 2019

‘I think, therefore I am’, and thus Descartes, in 1619, turned tables on humanity’s relationship to ‘Nature’ – at least in the part of the world where the dilemma of how to define what embodied ‘consciousness’ provided a scientific schema by which man could enact control. With such a decree, all manner of flora and fauna, with the view to better scientifically understand human mechanisms (and thus prolong their own mortality), became intensely medically and philosophically studied. Scientists identified an evolutionary likeness between humans and presumed non-thinking beings (ie. biochemistry; skeletal frames; cognitive function) yet they drew a superior line when it came to the human ability to doubt and reflect. Taxonomy was thus given a definitive exclusive measurement in the minds of these Western rationalists (which had tremendous impact on the way we visually relate to God, to our own species – think the rise of Colonialism and its implementation of racism). And thus began the destruction and degradation of our physical environment, with vast psychological and social ramifications. If animate forms of life could arguably exist without an ego, then the status of inanimate beings suffered even more astronomical annihilation, our planet today with irrevocable resource depletion due to the rise of Capital and its insidious expansion of industrialization. Tammy Nguyen’s series ‘The Gazing Pool for Who and Ai’, metaphorically ruminates on human desire and its narcissistic love affair with conquering its own perception of self. In this duo-exhibition with Ha Ninh Pham, titled ‘Necessary Fictions’, Tammy Nguyen illustrates the calamity of presuming imagination as only human coming back to bite, for here across myriad surface the interconnected force of Nature beams with an all-seeing eye, her multiple gaze boldly in challenge of Descartes and his superior claim of the human ego.

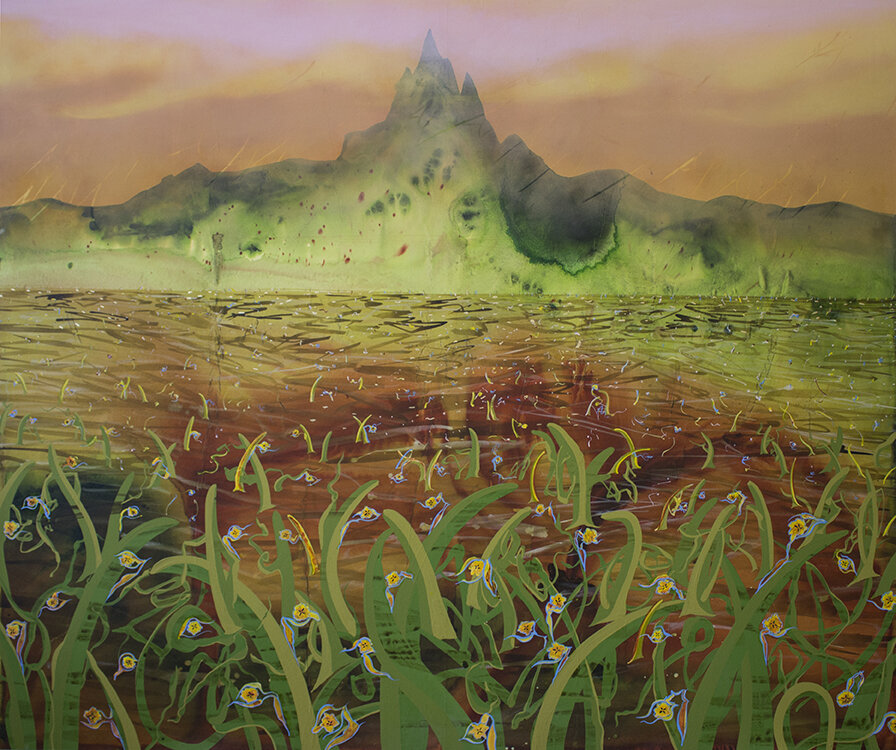

Daybreak, Break, 2019

In ‘The Gazing Pool for Who and Ai’, across 12 paintings and a series of moving sculptural installations, Tammy conjures her own fantastical tale of desire that parallels this aforementioned History and the fallibility of its rationality. It begins with a man who dares to remove the mask he wears in order to examine the image he gives to the world. Enraptured by this illusion (an image that cannot return his adoration), he follows his tears distortion of the ocean of the world, which he journeys into, taking him to the core of Mother Earth. He is re-birthed through the uterine water-wells of a cave, transformed, his eyeballs having given seed to the daffodil. As this gold and white flower he begins to re-populate the land, his petals a near camouflage shade of yellow, which resonates with the land and its ochre skin. Tammy pictures these daffodil, often wilting, beneath the ‘near perfection’ of Nature’s elements as the pressure of water and air collide; as the majestic sublimity of frozen mountain peaks claim yet another ambitious, naive explorer; as tornadoes efficiently annihilate; as the sun mercilessly beats its rays on its offspring. Disembodied hands reach out, attempting to grasp these interwoven elemental energies that empower this land, but in the end, the all-seeing eye controls elements and organism. Ironically (perhaps karmically), the daffodil is swallowed, ingested, (again?) by his ancestors. And so History repeats, for this is a tale of ‘non-fiction fiction’, a toxically beautiful referral to today’s corporatist and capitalist extremism laced with the irony of mythological insight, for she is indeed referring to the reality in which we now live, a conscience that has continuously failed to pay heed to the 8th Century classics of Ovid, whose epic ‘Metamorphoses’ poem first conjured the self-love of a man who became a daffodil.

Before the Touch, Touch, 2019

In Ovid’s tale, Narcissus, a man who knows his own beauty but cannot return the love it conjures for him in others, is being followed by a mountain nymph called Echo, who has fallen in love with him. He senses he is being followed and calls out ‘Who’s there?’ to which Echo shyly repetitively replies ‘Who’s there?’. She eventually steps out and attempts to embrace him. But he gruffly tells her to leave him alone and she is left heartbroken, a ghost echo in the woods. Nemesis, the goddess of Revenge learns of his actions and thus tricks Narcissus into a glade, towards a pool to quench his hunting thirst. He discovers his own youthful image reflected in the pool and, not knowing it is his own image, immediately falls in love. Not wanting to leave this presence, he soon realizes that this image cannot return his adoration and so he melts into a gold and white flower - the daffodil.

Near Perfect Conditions, 2019

This classic tale of the destructive power of self adoration and desire is what Tammy uses as conceptual frame in ‘The Gazing Pool for Who and Ai’, perceiving desire as the on-going driving force of human debasement, evidenced in our near blind faith in science and the rise of the machine (both human endeavors) having created a great violence on the world. Tammy embraces the irony of understanding man’s love of Nature (studying its power, its structure) as leading to Nature’s eventual demise, illustrated in the final painting as a curse (Ai Cursed Ai), where Narcissus is ingested by a human, thus questioning the moral compass of love if each time it equates to the devouring of self. The idea of self-cannibalization is of compelling inspiration to Tammy, through the witnessing of Nature’s wrath as a brilliant force to be reckoned (think of the way storm pressure systems provide the onset of harvest for crops; of how flame and its by-product can rejuvenate soil nutrient, as example). She satirically maps the irony of Nature’s violent necessities in Near Perfect Conditions where the barren earth farts as a green tepid mass lingers nearby with wilting daffodils under a sky with stunning battle between wind and rain (inspired by the Virginia weather climes of the Kelvin Helmholtz affect). In Echo of Mont Blanc du Tacul of Nusantara, a fictional mountain imagined in the tropical historic South East Asian maritime world echoes a love affair with Mont Blanc (the highest peak of the Swiss Alps) which here is anchored in a fetid brown watery haze. Here Tammy intertwines the human desire to conquer with the lure of Capital, mapping the desire to climb and leave a mark, with the urge to possess; aware that where it was once Empire that claimed land in her region of cultural ancestry, it is now Corporation that plunders (Nusantara being a Javanese word for a set of islands in the Malay Archipelago now trending as a name for corporate branding). Tammy’s worlding is a topsy-turvy picturing of the order of power, a resounding battle of ‘Ai Ai Ai Ai Ai Ai Ai’ (translated from Vietnamese as ‘Who Who Who Who Who Who Who’). This phrase is secreted across many of these pictures as cloud formation, tornado imprint, plant tendrils; a word also present in much of the titling of these paintings, which falls in alliance with the artist’s rendering of Narcissus as in constant transformation, in search of the love for himself (curiously the word ‘Ai’ in Chinese means ‘love’). But the begging of ‘who’ is also a contest of power over another, between Nature and Imagination, for lets not forget that the concept of ‘who’ is entirely human.

Ai Ai Ai Ai Ai Ai Ai, 2019

An epilogue to this little fantastical journey is So Long, Long For, a series of sculptures, composed of standing fan masked as blown up daffodil fronds, electrically breathing life into the gallery space. As the face of these fans rotate, small mirror shards on the ground refract light and color. These daffodil fronds are the remnants of Narcissus, his daffodil body persisting in fragments, his reflection forever in pieces, his body transplanted across the world as its own kind of colonizer (for lets remind that the introduction of foreign plant species into indigenous habitat has had some disastrous effects – think of the water hyacinth that is choking the Ton Le Sap river in Cambodia). But there is an additional insidiousness hinted with these mechanized fronds for they are now propelled by an alternate life force. Here, Nature is ‘improved’ (its energy force sitting outside its ‘organic’ matter) and thus the heralding of humanity’s dangerous obsession with artificiality and genetic engineering. But it is also a stark reference to the ‘arming’ of Nature (suggestive of a possible sequel narrative for the artist?), where the militarization of resource is of highlight – a horrifying reality for many community in the resource laden regions of the world (think the paramilitary role in the production of palm oil in Latin America; the arming of the seas in territorial disputes in the South China Sea; or the historic famines caused as a result of war-demand for planting jute during the Sino-Japanese war in South East Asia).

Weeping, Weeping, 2019

In the work of Tammy Nguyen there is respectful awe in the treatment of her subject matter, but also in its materiality. In Before the Touch, Touch and Passing By and By, her use of blue metal leaf allows its natural oxidation to take the fore as tinges of orange are revealed, giving layers to the subject of the Earth, these ripples recalling the wisdom of ancient rock formations such as the Grand Canyon. There is an adept mastery of line in these images also, as Tammy’s brush commands a rhythm across the surface of each, these brush marks with dynamic flow as they circle twin tornadoes, as eyes bleed, as water reflects. This attempt to give rhythm to her brush is in synergy with the use of repetitive motif in her narrative - the eye, the daffodil, the ‘Ai’ – a kind of visual haiku in honor of the myriad poets that have influenced her exploration of love and its terrifying multiple. Masterminds such as William Blake, Jonathan Swift and of course Ovid are key landmarks in her foraging for words that has seen her mine man’s relationship to Nature via the art of poetry. Ever vigilant of the need for an absorptive mind as an essential skill in learning, Tammy is also here proving her practice as absorptive with her handling of paper. In glee with its ability to handle water, here Tammy stretches and mounts paper to wood panel, an experience she excitedly describes as a body that ‘bounces back’ when liquid (such as watercolor, vinyl paint, pastel and metal leaf) is re-applied to its surface.

Passing By and By, 2019

Across these myriad painterly gestures is a cyclic sense of human constructs and the reprehensible inability for humanity to learn from its past, to consider the plight of both conscious and non-conscious beings in its thirst for progress, control and immortality. The art of Tammy Nguyen is testament to the invaluable resource of culture as a visual and textual set of necessary fictions that can provide an ethical compass with which to guide moral conduct, but her art also clearly reveals how easy it is for this compass to be instrumentalized, hoodwinked by the claim of our own image as supreme, argued as the survival of the fittest.

(1) First published in ‘Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One’s Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Science’, a philosophical treatise by Rene Descartes in 1637. It is arguably one of the most influential works in the history of modern Western philosophy.

(2) Referred as the Scientific Revolution, this birthing of modern science too place in Europe from the mid Renaissance period (16th Century), such explorations of physics, astronomy, biology was to pave the way the rise of empirical knowledge and a new understanding of Nature – science became an autonomous discipline (separate to the study of God).

(3) See Book 3 of Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’ (translated by Stanley Lombardo). Hackett Publishing, Indianapolis/Cambridge, 2010.

(4) A scientific phenomenon of element instability when velocity in a fluid creates a particular interface between two fluids – evidenced in cloud formations that appear in this particular painting of Tammy Nguyen. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kelvin–Helmholtz_instability

*

Zoe Butt is a curator and writer based in Vietnam. She is also the Artistic Director of The Factory Contemporary Arts Centre. Her curatorial practice centres on building critically thinking and historically conscious artistic communities, fostering dialogue among countries of the global south.